When looking back at the culinary masters, there is danger in getting so caught up in the interpretations of their work by subsequent followers that one assumes a slavish posture.

It is a position to be feared.

In Dialogues of Ancient and Modern Music, Galileo’s father challenged the kind of thinking of those who would later refuse to look through his son’s telescope knowing it could not show anything new.

“It appears to me,” he said, it was worth standing up against those “who in proof of any assertion rely simply on the weight of authority.”

He and his son’s desire was to “wish to be allowed freely to question and freely to answer [conventional shibboleths] without any sort of adulation.” It is with the same open mind that I offer these looking back to the future. Let’s look at these books with a new eye and expectations, avoiding the conventional scholarship that in the past has sought out only what is strange – mace, ginger, nutmeg and clove in “every” dish (untrue). Or Lord of the Rings mythical – how to roast a crane, stuff a sparrow, or skewer a snipe.

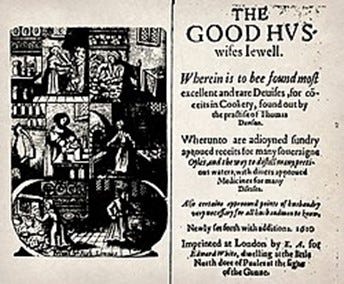

In the 1596 The Good Huswifes Jewell, there is not a mention of French cooking or the use of a French word. Perhaps that’s because Elizabeth the First would have thought Mary Queen of Scots and her French connections and affectations were out to poison her. A Book of Cookrye of 1591 is the same plane fare, though English. How to make white gingerbread, boil a leg of mutton with lemons, and make a syrup of violets.

But by 1615 Elizabeth’s throne has been taken over by Stuarts, all of whom had caste more than a casual eye across the channel at French niceties. In A New Booke of Cookrye of that year, the first recipe calls for larding a capon before poaching it with lemons “in the French fashion.” English food would never be the same. Until the 20th century when a Frenchman and London restaurateur called Marcel Boulestin (the first TV chef) had to remind English housewives that English food cooked simply should be a national pride, and towards the end of the century restaurants like London’s St Johns created a unpretentious temple to that food.

Their grilled chicken hearts on toast made my heart sing.

Soused oysters could easily have been on the menu as well. Here is a four-hundred-year-old recipe for them. “Take out the meat of the greatest oysters. Save their liquor and put it into a saucepan with half a pint [U.S. 10 ounces] of white wine and the same quantity of white wine vinegar. Add some whole pepper and sliced ginger and simmer for a minute. Then add the oysters and let them boil one minute only. Take the oysters out and chill the poaching liquid. Then put the oysters back in the liquid and hold [refrigerated] until you need them’, though perhaps not all year as the book allows.”

Sounds like a mignonette sauce treatment served in every restaurant that serves oysters!

It is not astonishing that my favorite recipe from the 1615 book is poached capon with the above soused oysters and pickled lemons. A similar recipe calls for putting some of the poaching broth in a pan with Rhenish wine, sweet herbs, mint, pickled lemons and oranges (use salt preserved ones), and then to cook some oysters in the mixture. If “you love the juice of an onion,” then add that to the oysters. I would forgo some “raisins of the sun” as offered as a variation.

It was from one of these books that the inspiration for oyster hollandaise hit me. I might just be tempted to poach the capon (after it is boned and then stuffed with mushrooms) and pour the oyster hollandaise over it.

Speaking of lemons.

A recent shipment of Meyer lemons from a garden in the Berkeley hills, unpacked to the music of the good-to-be-alive feeling in Brahms’ violin Concerto in D Minor #1 played by Pinchas Zukerman that talks to me of woodcock, its liver on toast, and champagne, made me think.

And while thinking of toast (and toasts) it seems to me that one or two of the refrains are all about toast and butter, and a lover who spreads it for you.

Why all that made me think of picnics, I don’t know. Perhaps because it is still cold outside, the pool still not as warm as I like it, and the melons are not yet ripe.

When they are I will take some small (each enough for one person) cantaloupe melons around four in the afternoon after the sun has beaten down on them all day. Then I will cut the tops off to make a lid, scoop out the seeds, strain them and the juices for putting back in the melon, fill the melons with at least 50-year-old malmsey Madeira, put the lids on, and then put the melons down a deep well in a bucket just above the water. I will leave them there overnight, and the next day, to finish off the picnic, I will get those melons out of the well, hand out spoons, and then we will all drink the melon-infused Madeira and spoon out the Madeira-infused melon flesh.

Short of that I will just have a lover plug in the toaster.

I started with these on Sunday morning when it was my job at age 8 to make the toast. At the table.

Then later I graduated to this type.

Now, when lucky, I have someone else do it. With whatever machine pleases them.

And while still cool, cook this.

French Vinegar Chicken

In France, this dish has been just as beloved as Coq au Vin or Boeuf Bourguignon. But much easier to make. And although it’s a cinch to prepare, the complex flavors of this chicken will make your guests think you’ve been prepping and simmering for days.

1 fryer chicken cut into serving pieces

1 teaspoons salt

¾ teaspoon ground black pepper

8 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons olive oil

6 ripe tomatoes, skinned, seeded and chopped—or good quality canned

1 cup red wine vinegar

1 cup chicken stock

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Combine the chicken, salt, and pepper in a bowl and toss it until it is fully coated.

In a Dutch oven over medium heat, melt 4 tablespoons of the butter with the oil. Add the chicken and sauté it until it is golden brown.

Add the chopped tomatoes and continue to cook until the tomatoes are fairly dry. Pour in the vinegar and let the chicken simmer until the vinegar has almost disappeared. Add the chicken stock and continue to simmer until it is reduced by ½ and then cover the Dutch oven. Place it in the oven for 30 minutes.

Strain the cooking juices. Whisk the remaining 4 tablespoons of butter into the sauce over high heat. As soon as the butter is incorporated turn off the heat. Add 1 tablespoon of chopped parsley to the sauce, whisk, and pour the sauce over the chicken.

Sprinkle with the remaining parsley and serve.

Thank you for reading Out of the Oven. If you upgrade for the whole experience, and pay $5 a month or $50 a year, you will receive at least weekly publications, as well as menus, recipes, videos of me cooking, and full access to archives.