Read all the stories from Slate’s 25 Most Important American Recipes of the Past 100 Years.

It was early the week of Thanksgiving 1959, and the young Knopf editor Judith Jones was trying to tie up loose ends before making the long drive north to Vermont, where her family would convene. She was deep in work when her colleague William Koshland stopped by her desk and handed a thick, unwieldy stack of paper over. Koshland, who hadn’t a clue about cookbooks, asked Jones if she’d weigh in on the submission. Everyone knew that Jones had spent years in Paris and had even run a private supper club out of her apartment on the Rue de Cirque.

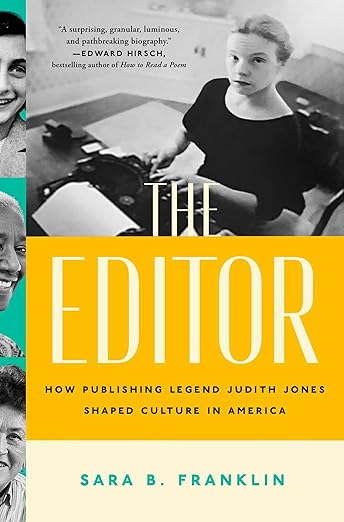

Jones eyed the manuscript. The book was huge—750 pages long. “French Recipes for American Cooks by Louisette Bertholle, Simone Beck, and Julia Child,” the cover read. Jones had been searching for a good French cookbook since returning to the States. The American foodscape had shifted radically in the postwar years, with small grocers and specialty shops giving way to supermarkets that kept food in boxes and cans and behind glass. “Everything was going into packages so the ‘poor little woman’ wouldn’t soil herself with cooking, the ignominy of cooking,” Jones told me while I researched my book, The Editor: How Publishing Legend Judith Jones Shaped Culture in America.

Jones tried to make do. But she’d tried cookbook after cookbook, finding each one lifeless and uninspired. What rankled her most, though, was that the books didn’t work. At the time, most cookbooks relied on cursory instructions and assumed home cooks had a great deal of skill and knowledge. All that brevity and vagueness left ample room for improvisation (and error). Not one of the French cookbooks Jones tried offered the precision, detail, or depth of explanation she sought. She took the manuscript home and began cooking from it, starting with boeuf bourguignon.

If you prepare recipes from cookbooks, read culinary memoirs, watch cooking shows, or consume food-related content on the internet, you are—perhaps unbeknownst to you—under the influence of the late, legendary editor Judith Jones. It’s no coincidence, then, that four of the 25 recipes on Slate’s list of the most important recipes of the past 100 years—including that very bourguignon—came from books Jones shepherded into existence.

French Recipes for American Chefs needed work. Its comprehensiveness was one of its strengths, but Jones knew the book would benefit from a good pruning. And the recipes needed to be tested in the U.S. to make sure home cooks had access to the ingredients and equipment the book called for. But Jones saw its genius and promise; it walked home cooks, step by granular step, through preparing complex French recipes in such a clear, detailed manner that success in the kitchen was all but guaranteed.

No one at Knopf knew anything about cookbooks. They looked down on the genre. Food wasn’t the stuff of serious literature, it was the stuff of women’s pages. Jones, though, thought differently. She thought that if Americans only had the right tools and some encouragement, they would wake up to the pleasures of cooking and eating. She devised a wily workaround to pitch Child’s book to Knopf’s top editors (she wasn’t allowed in editorial meetings yet; she was too young and too, well, female). It worked. Once Jones had the project in her hands, she took it in her teeth and ran.

It took over a year of fastidious work to overhaul the manuscript that became Mastering the Art of French Cooking, months in which Jones and Child recognized in one another a shared proclivity for hard work and penchant for perfection. They also shared a politics, one that went against the grain of early second-wave feminism: Jones and Child believed the kitchen didn’t have to be a site of drudgery and oppression, but could rather be one of creativity, cultural exploration, and sensual pleasure.

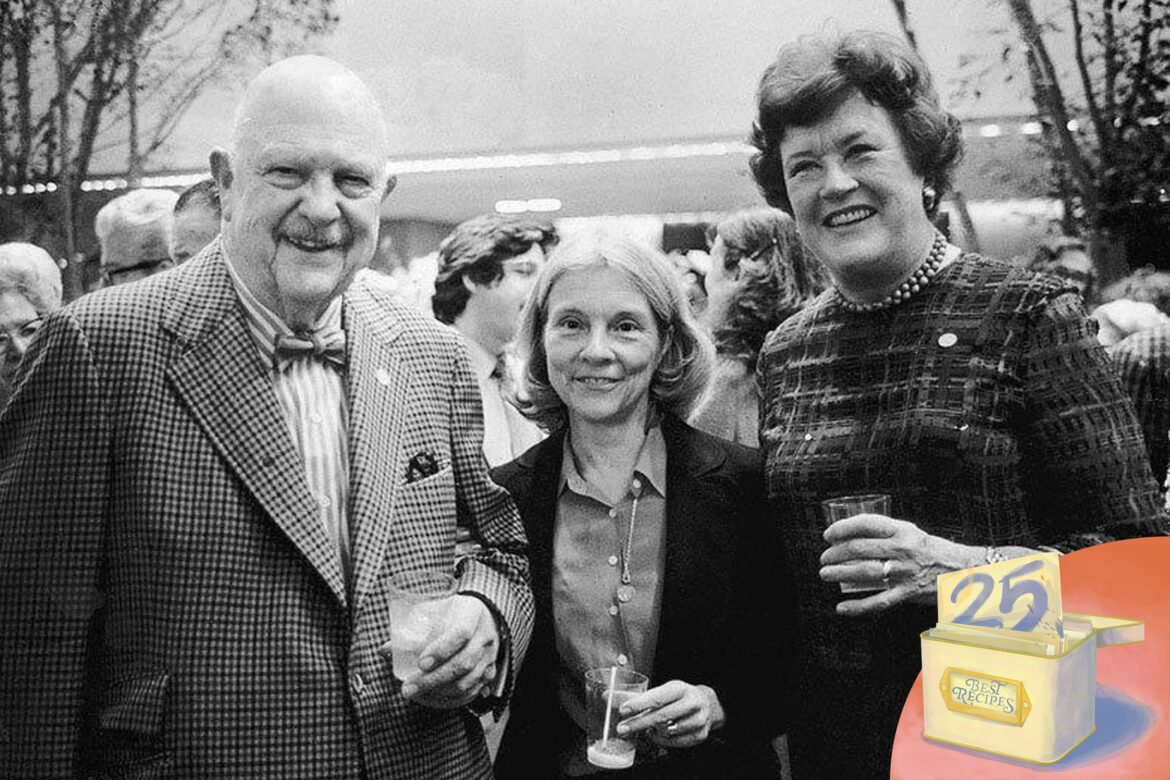

In the fall of 1961, Knopf published Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Jones understood that books needed help finding an audience, so she cold-called Craig Claiborne, who’d recently become food editor at the New York Times, and James Beard, a beloved and central figure in the then tiny world of food, and enlisted both of them to help launch the book. Mastering took off. By the end of the book’s first week in the world, Knopf had ordered a second printing of 10,000 copies more, doubling the book’s run, and had already made plans for a third round of the same. The senior editors at Knopf were stunned, but no one was more pleased than Jones and Child, whose joint, symbiotic labor had made the book what it was, and who had launched each other’s careers in food.

By Sara B. Franklin. Atria Books.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

Jones had a feeling that other authors could do for other cuisines what Julia Child had done for French food. And while she also worked with literary heavy hitters—she discovered the novelist Anne Tyler, and edited both her and John Updike, among other luminaries, for decades—it was the cookbooks she edited that made her a legend.

Jones rescued Madhur Jaffrey’s An Invitation to Indian Cooking from a publishing house that had abandoned it; the book was, for many Americans, their first introduction to Indian cuisine and culture. She encouraged Anna Thomas, a college student from California, to write The Vegetarian Epicure, a hit with counterculture and mainstream cooks and eaters alike. She found a singular voice and perspective in the stories and recipes of Claudia Roden, whose Book of Middle Eastern Food Knopf published in 1972. She convinced James Beard to write Beard on Bread, which came out in ’73.

And she became a true collaborator with Edna Lewis, one of the most influential and iconic voices in American cooking. Lewis was Black, the granddaughter of formerly enslaved people who had helped settle a farming community called Freetown in Virginia’s Piedmont region. Knopf published Lewis’ The Taste of Country Cooking in America’s bicentennial year, making a powerful, celebratory statement about the influence of the African diaspora on American culture, and of Black cooks on what we’ve come to think of as American food. Lewis dedicated the book to the people of Freetown, and to Judith Jones “for her deep understanding.”

Dan Kois and J. Bryan Lowder

The 25 Most Important Recipes of the Past 100 Years

Read More

The 15-year span between the launch of Mastering and Edna Lewis’ Taste were some of the most tumultuous and formative in American culture; movements for Civil Rights, women’s liberation, environmental conservation, and an end to the Vietnam War rocked the nation, and the rise of identity politics and an overhaul of America’s immigration policy raised important questions about who, and what, counted as American. The cookbooks Jones worked on, and the authors with whom she collaborated, did the same, both mirroring and shaping shifts in American culture.

Jones’ editorial skills and prowess, her dogged attention to detail, and her devoted, intimate collaboration with her authors are now the stuff of legend. But her particular genius was in using food as a lens, and cookbooks as a form, to bring people to the literal and proverbial table, encouraging them to communicate across differences of race, religion, nationality, region, gender, sexual orientation, and class—sometimes without their even knowing it—through the universal language of food.

Though other forms of media—glossy magazines, cable TV, and, later, the internet—began to take up more of the food space starting in the 1980s, Jones continued to make influential cookbooks right up until she died in 2017, 60 years after she started at Knopf. All of which is to say: The way we cook and eat—indeed, the way we live—has been under Judith Jones’ influence for a long time now. We are all the better for it.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.