By all accounts, this year’s Swartland Revolution was a triumph. The wines were thrilling, the crowd suitably adoring, the hangovers probably manageable (see Michael Fridjhon’s piece here). But the question I can’t help but ask – perhaps because I wasn’t there – is this: Can we still, in good faith, call it a revolution?

Granted, some creative licence was being exercised when the event was first conceived, and yes, there’s still brand equity to be leveraged. But at what point does a word like “revolution” start to feel a little glib – if not outright distasteful?

After all, we live in a country where a real revolution – against systemic repression – was fought and, in part, won. As we approach Freedom Day, marking 30 years since South Africa’s first democratic elections, it seems worth pausing to reflect on what’s at stake when using terminology that carries such historical weight.

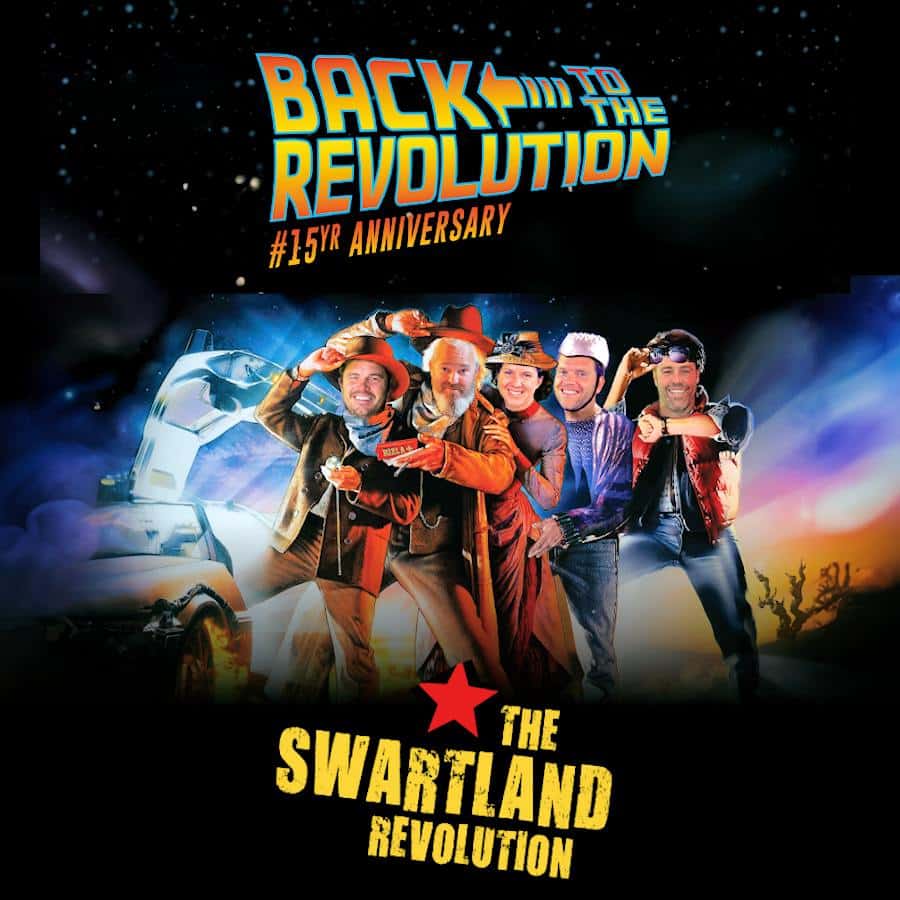

This year’s Swartland gathering marked 15 years since the inaugural event. Back in 2010, there was something stirring. The South African wine industry was in flux: the KWV had long since relinquished its statutory powers, transformed from super-cooperative to corporate entity, and the comforting blanket of price supports and surplus removal was gone. Grape growers, understandably distressed, began exiting the industry in alarming numbers – from 4,786 in 1991 to just 2,350 in 2023.

At the same time, however, the number of cellars crushing grapes soared, peaking at 582 in 2011. The Swartland “Revolution” emerged to prove that independents not only had a place in the new order but could thrive. And indeed, the Fab Four – Badenhorst, Mullineux, Porseleinberg, and Sadie – have gone on to build wildly successful brands, re-shaping perceptions of what South African wine can be.

But herein lies the rub: if revolution implies systemic transformation – something that benefits the many, not just a charismatic few – has that actually happened?

The broader picture tells a more sobering story. In 2024, South Africa’s vineyard area shrank to 86,554ha, down 15% from its 2006 peak. Grape supply is tightening, and while we remain the sixth-largest exporter by volume, we’re still outside the top 10 in terms of value. Premiumisation might come easily to the Swartland’s stars, but it remains elusive for the rest.

Let’s not forget: revolution, properly defined, is about overturning entrenched systems, establishing new structures, and delivering lasting benefits for the majority. Mere regime change won’t cut it – true transformation is deeper, more inclusive, more enduring.

Have the Swartland icons revolutionised South African wine? Certainly – for themselves. But perhaps they now serve more as outliers, a reminder of how resistant the broader industry remains to real change.

Of course, some readers might be tempted to dismiss all this as sour grapes. As mentioned, I wasn’t at the event. At R9,500 a head (before travel and accommodation), I couldn’t justify the spend. The organisers made clear no media would be invited – saying it was too tricky to choose who made the cut. I would respectfully suggest that refusing scrutiny is, in fact, a classic counter-revolutionary stance.

Still, I’m not cynical enough to think the revolution is over. If its core ideals remain unmet, then perhaps it’s time for a reboot – one grounded in today’s realities, broader in reach, humbler in tone, and bold enough to face the hard questions.

Because if we’re still calling it a revolution, then surely we owe it to ourselves – and the industry – to make sure it actually is one.