Since bottles of olive oil are notorious for having difficult-to-read labels that are often confusing or misleading, we spent lots of time examining them—and speaking to olive oil expert Kathryn Tomajan to learn more.

Generally, the more information provided on a bottle of olive oil, the better (much like wine). If you’re browsing olive oils in the store, it’s helpful to be familiar with a few terms so you can make an informed decision. Most people probably know to look for extra-virgin olive oils, but that’s just one piece of the puzzle. Ultimately, your taste buds will be your best guide, but here are some important details to help steer you in the right direction.

Extra-virgin olive oils are lab- and taste-tested to make sure they’re free of any defects. Photo: Michael SullivanExtra-virgin olive oil

Extra-virgin olive oils are lab- and taste-tested to make sure they’re free of any defects. Photo: Michael SullivanExtra-virgin olive oil

This is the highest grade olive oil you can buy; it’s lab- and taste-tested to make sure it’s free of any defects (here’s an example of a lab report from Fat Gold). Excessive heat and the use of chemicals are also prohibited in the extraction process. While extra-virgin olive oil has no agreed-upon global (or nationwide) quality standard, Tomajan said the differences between various extra-virgin certification standards are relatively negligible from a shopper standpoint.

You may occasionally see oils labeled as “virgin olive oil,” which means they’re subject to the same extraction standards but had minor defects that earned them a grade below “extra-virgin.” Refer to the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA; PDF) and the International Olive Council for more specific definitions.

This oil isn’t extra-virgin, but the supplier makes it clear that it’s a blend of refined and extra-virgin olive oils. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Another example of an olive oil that isn’t virgin or extra-virgin. Photo: Michael Sullivan

This oil isn’t extra-virgin, but the supplier makes it clear that it’s a blend of refined and extra-virgin olive oils. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Olive oils that aren’t extra-virgin or virgin

Olive oils that aren’t extra-virgin or virgin

You may see various olive oils in the grocery store that don’t say “extra-virgin” or “virgin” anywhere, and are instead labeled as: olive oil, pure olive oil, light olive oil, premium olive oil, or cooking olive oil. Often, they’re just a blend of refined, virgin, and extra-virgin olive oils (see the CDFA’s definition for refined olive oils here).

These oils are typically cheaper, and won’t have much (or any) olive oil flavor. So unless you’re aiming for neutrality or low cost (or both), one expert we spoke to recommended sticking with olive oils classified as extra virgin.

You should always look for a recent harvest date. This dusty bottle of oil from 2017 was still sitting on store shelves in 2023 and is most certainly rancid. Photo: Michael Sullivan

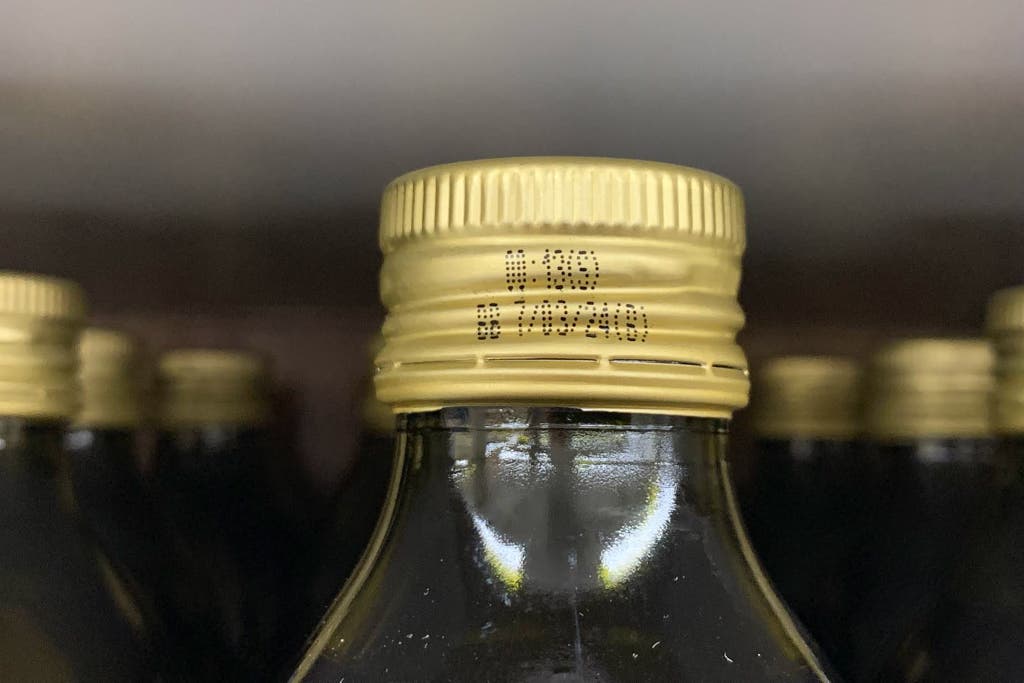

The best by date—seen here on the bottle cap—is not always a good indication of freshness. Photo: Michael Sullivan

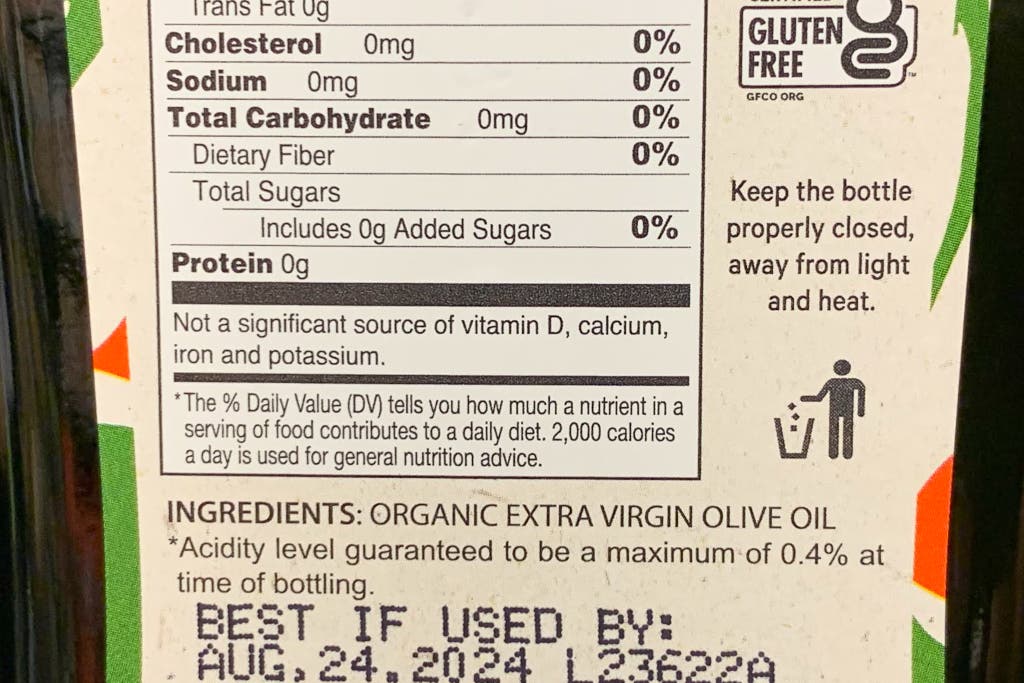

Another example of a “best if used by” date on a bottle of olive oil. Without a harvest date, you have no way of determining how fresh the oil is. Photo: Michael Sullivan

An example of an olive oil harvest date. Photo: Michael Sullivan

You should always look for a recent harvest date. This dusty bottle of oil from 2017 was still sitting on store shelves in 2023 and is most certainly rancid. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Harvest date

Olive oil is best consumed within two years of the harvest date. Unfortunately, most supermarket olive oils don’t provide their harvest dates (likely because they’re combining a blend of oils from around the world with differing harvest dates). The date labels on packaged foods are somewhat arbitrary, so if the bottle lacks a harvest date, you have no idea how fresh the oil actually is. Look for the most recent harvest date you can find. Note: The harvest date is often written as a range of the season and not necessarily a single year (for example, 2022/2023).

Designation of origin certifications, such as PGI or IGP, can give you some added assurance that the oil is indeed from a particular region and has been vetted by a third party. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Look for European oils with a designation of origin certification, such as DOP. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Designation of origin certifications, such as PGI or IGP, can give you some added assurance that the oil is indeed from a particular region and has been vetted by a third party. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Certifications to know

Certifications to know

Third-party certifications, such as the Applied Sensory Olive Oil Taste Panel, can help give you some added assurance beyond a label that just says “extra-virgin.” For olive oils made in California, you may see certifications from the Olive Oil Commission of California or the California Olive Oil Council (Yes, it’s confusing). The North American Olive Oil Association is another common certification.

If it’s a European oil, look for a designation of origin certification, such as PGI, PDO, IGP, or AOC, depending on its origin. You still want to look for a harvest date in tandem with certifications, otherwise you have no way of knowing how long the oil has been sitting on store shelves.

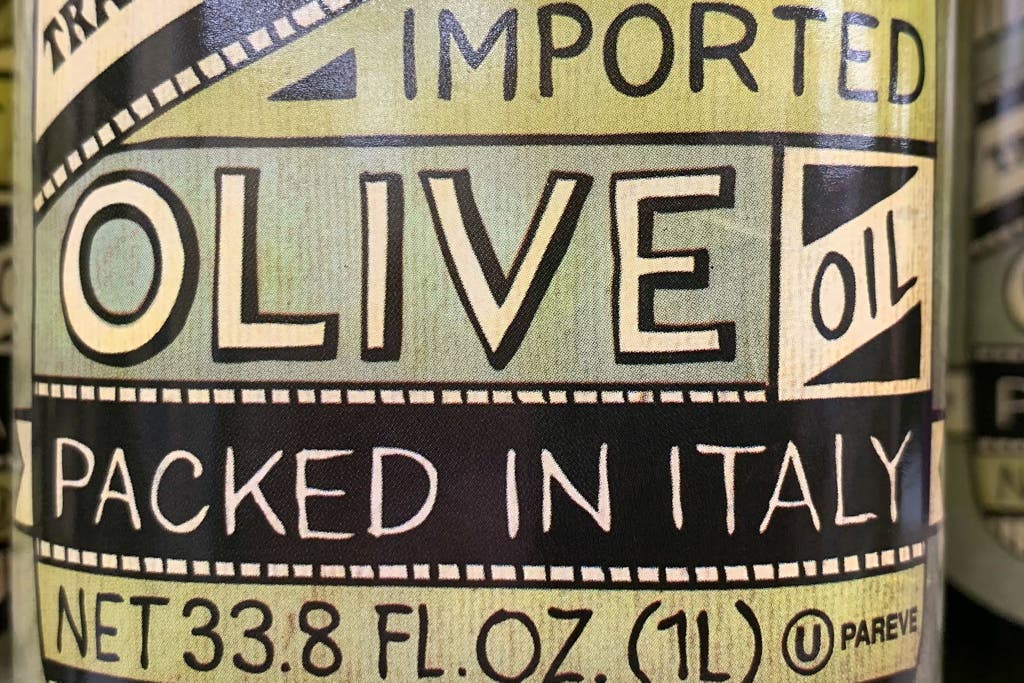

The phrase “packed in Italy” doesn’t mean the olives are actually from Italy. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Imported olive oils aren’t necessarily from the region listed on the front label—refer to the back label to determine the origin of the olives. Photo: Michael Sullivan

The phrase “product of Italy” means the olives were grown in Italy. Photo: Michael Sullivan

This label tells you that the olives are from both Spain and Italy. The oil was packed in Italy, but not all of the oil in the bottle is from that region. Photo: Michael Sullivan

The phrase “packed in Italy” doesn’t mean the olives are actually from Italy. Photo: Michael Sullivan

Origin

The country of origin is required for olive oil labels. Olive oils that say they’re a “product of” a particular region means the olives were grown there. If an oil is labeled “imported from” or “packed in” a particular region, the olives weren’t necessarily grown there (Spain and Italy are actually the top exporters and importers of olive oil), so always refer to the back label to find the specific origins. Olive oil blends often combine oils from regions across the world—typically the initials of the various countries of origin will be listed on the label.

Bottles of extra-virgin olive oil will typically say “cold pressed” or “first cold pressed.” This terminology is outdated, since most oil is now extracted using mechanical presses, but the verbiage persists. Photo: Michael SullivanCold pressed

Bottles of extra-virgin olive oil will typically say “cold pressed” or “first cold pressed.” This terminology is outdated, since most oil is now extracted using mechanical presses, but the verbiage persists. Photo: Michael SullivanCold pressed

According to the CDFA, “cold pressed” means the olives were pressed or crushed using a mechanical, hydraulic, or centrifugal press at a temperature that doesn’t lead to significant thermal alterations of the oil. Olive oil expert Kathryn Tomajan said this term is a holdover from before most oils were extracted using stainless steel crushers and centrifuges. Many people still think they need to look for this terminology on the label, so producers continue to include it.

You may also see the terms “first pressed” or “first extracted,” which Tomajan said implies that the oil is extracted from fresh olives only—never a second extraction from olive pomace. But this terminology is also redundant, as any extra virgin olive oil is, by definition, always both cold- and first-extracted.

Filtered versus unfiltered

“Unfiltered” doesn’t mean the oil is less processed. In Tomajan’s opinion, the best olive oil producers filter their olive oil, which means the residual water and particles have been taken out at the end of the production process. This process protects the oil from premature oxidation and doesn’t affect the nutritional value of the oil. Generally, she said, you want your olive oil to look clear, not cloudy.

This article was edited by Marilyn Ong and Marguerite Preston.