When 25-year-old Savin Edirisinghe stepped onto the stage to receive the 32nd Gratiaen Prize for his debut short story collection Katakata, he brought with him more than just a book. He brought an entire generation of young Sri Lankans who write in English yet dream in multiple languages, who navigate everyday life with a poet’s soul, and who find inspiration in the most unlikely places—buses, petticoats, whispered gossip, and quiet suffering.

For Edirisinghe, the win was not just personal triumph—it was, in many ways, a statement of cultural evolution. Speaking to The Sunday Island, he said:”If I can win the Gratiaen, anyone can,” he said with a smile that belied both humility and disbelief. “English is not my mother tongue. I didn’t grow up immersed in English literature. But I write in English because it’s one of the languages I feel most at home in.”

The Gratiaen Prize, Sri Lanka’s most prestigious literary award for writing in English, has over the years served as a springboard for some of the country’s most acclaimed voices. Yet this year’s winner represents something refreshingly new: a voice grounded in urban and semi-urban life, unapologetically local, but delivered with literary elegance and poetic flair.

The Power of Gossip and Story Telling

The title Katakata—a Sinhala word that loosely translates to “gossip” or “chatter”—was carefully chosen. “That was my marketing brain at work,” Edirisinghe smiles. “I work in advertising during the day, so I know how important a good title is. But it also fits the stories. These are tales stitched together from things I’ve overheard, stories shared in passing, or little dramatic moments I’ve imagined based on real people.”

Despite the gossipy premise, Katakata is not sensational. It is introspective and rich with emotional texture. “I think we gossip because we want to live, for a moment, inside someone else’s life,” he explains. “It’s a way to understand desire, frustration, dreams—everything we suppress in ourselves. Writing is like that too. It’s about living other people’s lives in a very intimate way.”

The characters in Katakata—while often surreal or absurd—are inspired by real individuals. Friends, acquaintances, strangers on public transport. “They won’t recognise themselves,” Edirisinghe insists. “They’ve been altered, reshaped, sometimes exaggerated. But they all began as someone real.”

The collection, sprinkled with magical realism and absurdism, explores themes of desire, repression, identity, and societal contradictions—particularly the unseen lives of Sri Lanka’s working and middle classes. What makes the work stand out is how Edirisinghe blends lyrical prose with earthy, grounded subject matter.

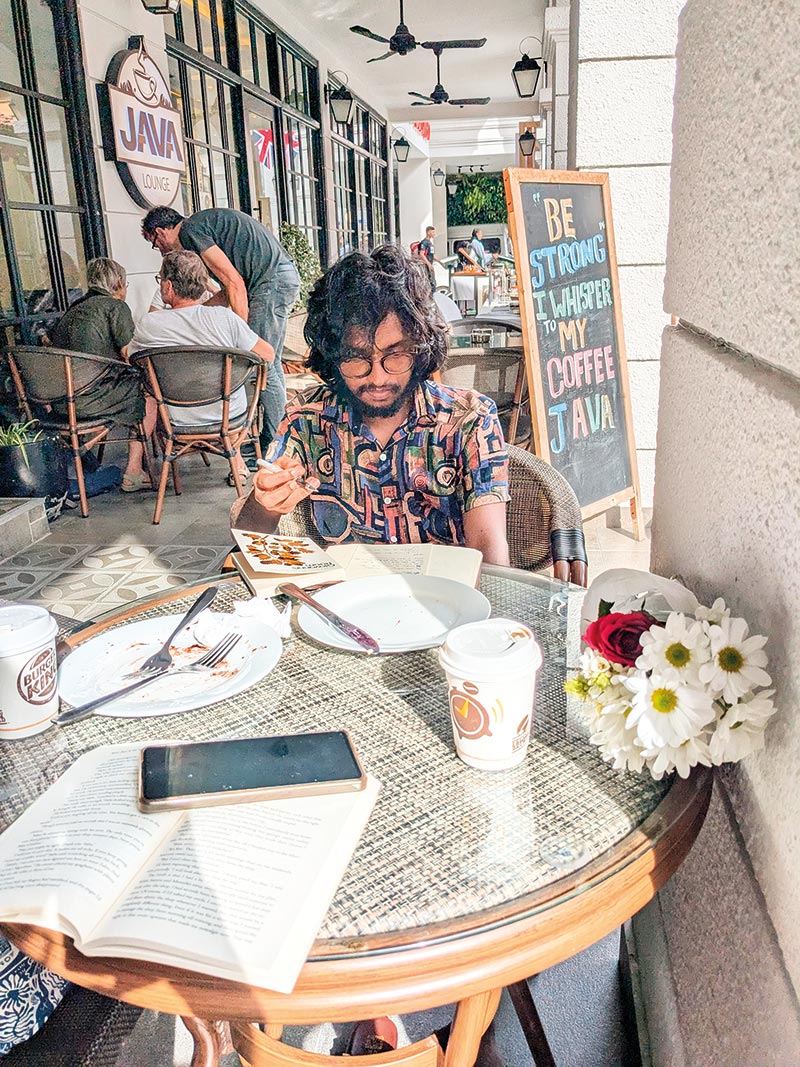

Savin

A Poet First, a Storyteller Always

Edirisinghe prefers to be called a poet. “I write more poetry than prose,” he says. “Even when I write fiction, the poetic rhythm sneaks in. That’s how I express myself best.”

His literary influences reflect this dual sensibility. “Oscar Wilde, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, and of course Shakespeare,” he lists, adding Sri Lankan names with equal reverence: Mahagama Sekara, Yamuna Malini, and lyricist Rathna Sri. “I admire people who can take language and make it sing.”

His childhood, he recalls, was steeped in stories—thanks to his father, a dramatist, writer, and journalist. “To get me to sleep, he’d tell me two or three stories each night. And when he ran out of real stories, he made up new ones. I always knew which ones were made up—but I loved them even more.”

From those early beginnings came a young boy scribbling stories on A4 sheets, cutting and pasting images from magazines, and rewriting the endings of books he’d already read. That instinct to take the familiar and reshape it still defines his work today.

A Complicated Love Affair with Writing

“I have a toxic relationship with writing,” Edirisinghe says candidly. “But it’s filled with passion. It’s the only thing I know how to do.”

He compares his relationship with writing to Lionel Messi’s with football. “It’s like breathing for him. And for me, writing feels the same. If you took it away from me, I wouldn’t know who I was.”

Yet it’s not always easy. “Sometimes I want to write something so badly, but I just can’t get it right. That leads to frustration, even anxiety. But I keep at it. Because that’s what you do when you love something.”

His advice to young writers? “Write until you feel right. You may never feel completely satisfied—but in the process, you’ll create stories, poems, maybe even a script or a novel. Just keep writing.”

Writing What You Know

In his acceptance speech, Edirisinghe urged writers to write about what they know. “I can’t write about tulips or winter—I’ve never experienced them. But I can write about bus rides, petticoats, and the absurd things we encounter every day.”

That doesn’t mean he’s limited by reality. “Even sci-fi is believable when the emotions are true. You don’t need to live in space to write a compelling story. You just need to find a connection—something that makes the story feel alive.”

This is perhaps Katakata’s greatest strength: its ability to turn the mundane into the magical, to find poetry in the ordinary, and to reflect deep truths without sounding didactic or moralising.

Book that won acclaim

A Platform for the Youth

Edirisinghe credits the Future Writers Programme—a mentorship initiative—for helping him find his voice. “That was my first real exposure to the English literary scene in Sri Lanka. I met mentors like Professor Lal Medawattegedera and Ashok Ferrey. They gave me the courage to edit, to submit, and to believe I had something worth saying.”

He won the Future Writers Programme last year. This year, he took the Gratiaen Prize. “I think the Programme is a great stepping stone. It should be expanded and continued. If I hadn’t gone through that, I wouldn’t be here.”

For him, the Gratiaen win isn’t just validation—it’s an opportunity to open doors for others. “This award is often seen as something for Colombo elites. But now, people from outside the city—people who don’t even read in English—are talking about it.”

He recounts a call he received after the awards ceremony—from the man who used to read the electricity meter in his neighbourhood. “He found my number and called to say thank you for writing these stories. He said, ‘It’s refreshing to see someone like you win.’ That meant everything.”

Literature as a Soft Power

Beyond personal glory, Edirisinghe sees literature as a nation’s soft power—one that Sri Lanka must harness. “Look at what Shyam Selvadurai, Michael Ondaatje, and more recently Shehan Karunatilaka have done. Sri Lankan literature has global potential.”

He points to India’s thriving literary scene, and even Sri Lanka’s youth making waves on global platforms—from Anagi Perera at Miss World to Sri Lankans on the Forbes list. “We are showcasing the diversity of Sri Lanka—not just in identity, but in talent. Literature should be part of that.”

He dreams of a day when Sri Lankan literature—particularly English writing by locals—finds a global readership. “We have stories that the world needs to hear. But we need platforms, we need visibility, and we need writers who dare to write authentically.”

A New Chapter Begins

With Katakata, Savin Edirisinghe has opened more than a door for himself—he’s cracked open a window for a new kind of English literature in Sri Lanka: playful yet profound, deeply local yet accessible to all.

“I wanted to be different,” he says. “My father always said, ‘Be extraordinary among the extraordinary.’ That stuck with me. Even when I wish someone a happy birthday, I don’t just say it—I find a new way to say it.”

That same philosophy defines his writing: unexpected, lyrical, sincere. In Katakata, the mundane becomes magical, the gossip becomes gold, and every sentence pulses with life.

The award may have gone to one young writer, but the ripple effect could shape an entire literary landscape. “Now people who never imagined themselves submitting to the Gratiaen might just try,” he says. “That’s a win for all of us.”

By Ifham Nizam ✍️