Author Polina Chesnakova. Photo by Dane Tashima.

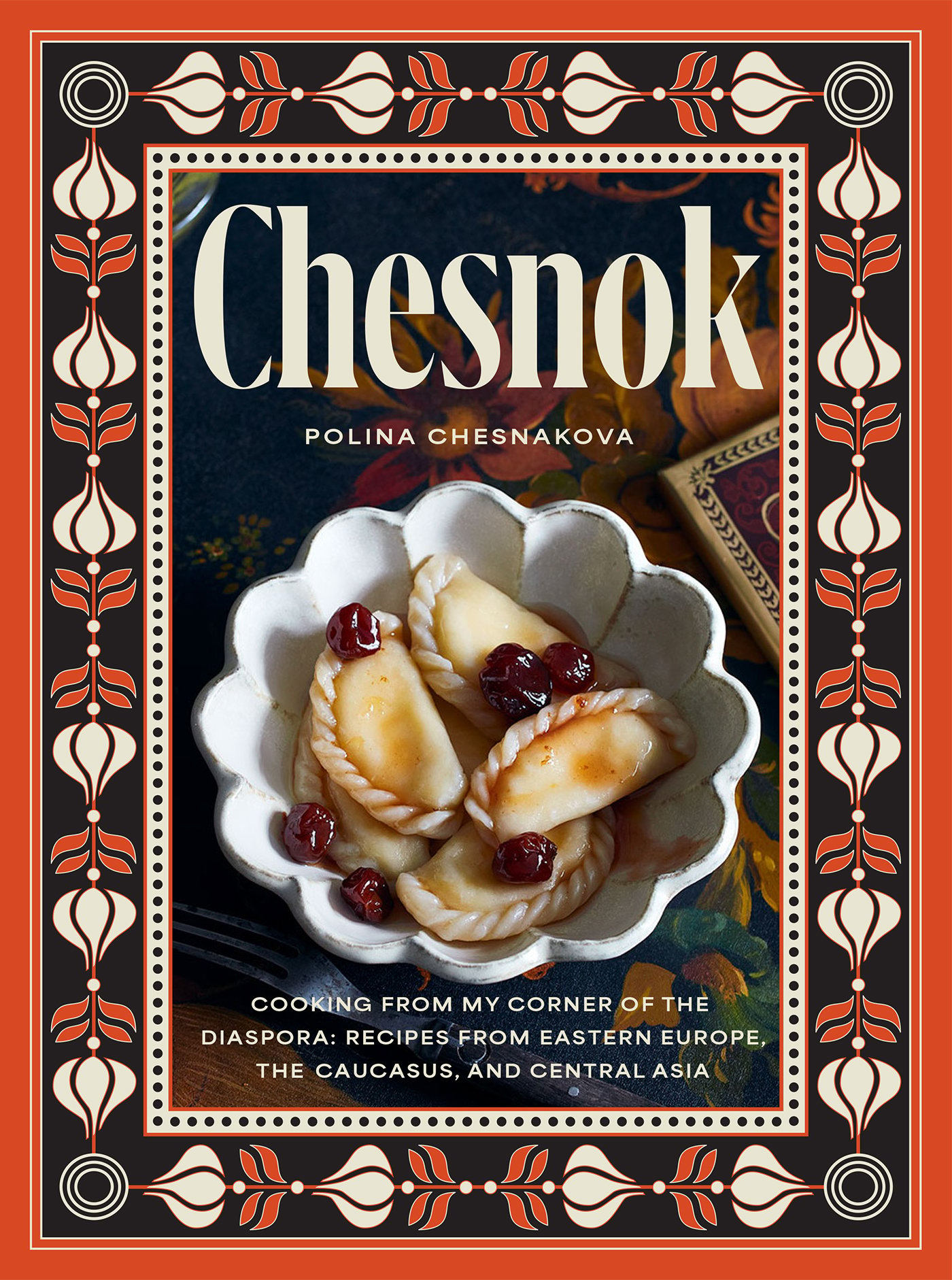

Chesnok is a new cookbook from Polina Chesnakova, who tells the story of her family’s immigration from Eastern Europe to the United States through food. The Soviet Union disbanded in 1991, which created a diaspora in Eastern Europe, with many fleeing the area to the United States and other countries. Chesnakova was born in Ukraine but immigrated to Warwick, Rhode Island, with her family when she was just three months old. A child of Russian and Armenian parents from Georgia, Chesnakova’s recipes span Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia with ingredients and techniques that cross cultures. She grew up eating all her aunts’ and mother’s recipes at family gatherings and learning to cook at their hips. “Chesnok” is the Russian word for garlic, which is a major ingredient in their cuisine, and it’s also a play off of the author’s last name. Chesnakova’s book is divided into sections including Breakfast; Dumplings, Pastries, and Breads; Soups; Vegetables and Salads; Meats and Seafood; Grains and Legumes; Ferments, Pickles, and Preserves; and Sweets. Learn all about her cultural journey through food in Chesnok.

How did you first come to the United States?

I was born in Ukraine, and we immigrated to the US when I was three months old in September 1992. We landed in Providence, but I more or less spent most of my upbringing in Warwick.

In the book, I know you get into your family’s history in the Soviet diaspora. Can you give us a summarized history of how your family came to be here in the United States?

My mother is Russian, and my father is Armenian. They both were raised in Georgia in the Soviet, and they saw the writing on the wall. Things were starting to take a turn, and they were one of the lucky ones to be able to get out fairly early in ‘92. My mother’s sister (my aunt) and her husband had moved to Rhode Island earlier. So they encouraged my parents to move to Rhode Island as well. We moved in September 1992, and slowly, more of my mom’s sisters trickled in over the years. So we had each other. My mom was one out of eleven, and five sisters ended up in Rhode Island. I grew up in a big, boisterous Russian family with lots of cousins. So that was one part of the equation. And then the other part is that shortly after we landed, there were a lot of refugees coming from the former Soviet Union, and there was a community that started to build in Rhode Island.

So you started to build your own community?

There was a group of families that started to congregate in the early ‘90s. It was a reflection of refugees from all over the former Soviet Union. And so the founding families were from Estonia, Ukraine, Russia. And as that congregation grew, so did representation from all over the former USSR. I grew up in communities of immigrants. My family is predominantly Russian, but I grew up with friends who were Ukrainian and Armenian, and I had friends from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. And so when I started writing this book, it was really important for me to document my family’s recipes, and then taking a closer look, I realized there’s so much representation from other countries as well, and that was just a reflection of the sort of melting pot of cultures that I grew up with.

So was your community in the West Bay, in Warwick specifically? Or was it people coming from all over the state?

We started getting together at a church in East Providence. I think it used to be called Second Baptist Church. If you take that East Providence, East Riverside Avenue exit, and take the left ramp on Taunton Ave., it’s that big church right on the corner. The church was growing, and eventually we were able to raise enough money to buy the building outright. The members were coming in from all over the state.

East Providence is such a melting pot. I know it’s known for its Portuguese community, but I didn’t realize there’s also a whole Soviet/ Russian community as well. Were there places like restaurants that you grew up going to that cooked familiar food from home?

We were working class, so going out to eat was a special occasion. It was mostly like going out to Olive Garden. But all the recipes that you see in my book, and all the food that I grew up on, was all home cooking. My mother and my aunts are fantastic cooks, and we got together often. Food was always a big focal point. At church, we would often have potlucks, and everyone brings something. There were family favorites that reflected where everyone was from and it was a multicultural smorgasbord.

That sounds so awesome. And I know you open your book with insight into what the holidays are like in your household with all your family members. Can you explain what that atmosphere is like when you’re prepping for a big family gathering and everyone coming together?

It’s just a big, big family affair, and we spend weeks getting ready for it. Every family has an assignment of which dishes they’re going to bring. There’s lots of delegating, lots of bickering, there’s always the debate of “Will we have enough food? Should we add this dish? Is that too much or not enough?”

It’s hard to tell how much to cook.

And in my family, more is more. You can never have too much food. It’s always better to have too much food, because then you can enjoy the leftovers. It’s definitely a team effort, getting the holiday table together. Usually we get together in the afternoon, and it’s a full day affair of eating and taking breaks and coming back to the table again. Eventually, towards the evening, we roll out tea time. And of course, it’s a full-on spread. There’s no such thing as one dessert in my family. So we have something with fruit, something with chocolate, something with cream. We pick up chocolates from the Eastern European store. It’s an all day eating extravaganza.

I want to be a guest at that party. So you have one son who is three and a half and a baby girl on the way. Does your son eat a lot of the traditional foods at family parties?

It depends on the day, the mood, how hungry he’s feeling. But one dish that is always a favorite with everyone, but especially kids, is the cheese bread from Georgia, where my family immigrated from. They have many different versions, depending on which region you’re from, and the one that we make, especially for big family parties, is called penovani khachapuri; penovani meaning flaky. We have a shortcut, kind of like a hack for making it, where we use store-bought pastry and make it into a sheet pan version. It’s two layers of pastry filled with gooey, melty cheese. Every kid, no matter how picky they are, they love that.

It sounds like a grilled cheese but different. And what are some of your favorite recipes in the book?

The tabaka-style adjika chicken. That is probably one of my go to recipes. It’s how we marinate and roast chicken. We use the adjika which is a Georgian chili paste. It’s essentially a spatchcock roasted chicken, and we marinate it in this Georgian chili paste called adjika. And if you can’t get your hands on it, my mom will often use the Portuguese hot crushed peppers.

I actually have that in my fridge!

I didn’t realize it was an international thing, until I left home for college. But it’s very much a Rhode Island/Portuguese ingredient. So for those in Rhode Island, it’s a great substitute, and you can find it in all the stores. It’s a chili paste, and you mix it with mayo, cilantro and fresh garlic, and you have the heat from the chili paste and the mayo carries that flavor, locks in the juices and keeps the chicken super succulent. So that is my favorite way to roast chicken. You can use it as a marinade for grilling, roasting or pan-frying it.

I want to make that in my home. I’m sure it will be a hit!

Another favorite is the dumplings. I have a handful of dumpling recipes. I love the Ukrainian varenyky, and you can have them either savory or sweet. I grew up eating that at my Ukrainian friend’s house. Their mom always served ones filled with farmers cheese, kind of like cottage cheese.

Portuguese people have farmer’s cheese like that too.

I think Germans have similar versions called quark that are filled with farmer’s cheese. They’re really good, topped with a dollop of sour cream and a sprinkling of sugar. It’s super comforting, very nostalgic. Or if you can get your hands on sour cherry. You will often find them filled with fresh sour cherries. In the book, I have a recipe for a sour cherry compote to top off the dumplings.

Oh, that sounds amazing. Does it take a lot of time to cook this type of food, or are you able to squeeze in something on a weeknight?

Dumplings are always going to be an afternoon affair. And it’s always nice to invite a family member or friend to help you move that process along. Then you can make a lot and freeze them. So then they do become weeknight-friendly. The chicken, that’s pretty weeknight-friendly. But then you also have a lot of these dishes that take a little bit more time. My mom and my aunt were all working while also being in charge of feeding their families. So they would always make recipes, these big, one-pot recipes that lasted for a few days, so they’re not stuck in the kitchen every night.

That’s how I strategize too!

Yes, like my family, the borscht recipe makes this giant pot to feed a small army. You put a lot of work into it, but then you’re enjoying it for many days. And you can freeze what’s left. And the golubtsy, the stuffed cabbage rolls recipe makes a big portion. They freeze really well, and you can enjoy it for many days afterwards.

Yeah, if you’re gonna get all those dishes and pans dirty, you may as well go big. That’s how I feel.

In the Vegetables and Salads section, you have these salads that come together really quickly. But this book is not thirty-minute weeknight dinners.

That’s what makes the recipes so good, and totally worth it, as you said. What’s one thing you want people to know about your book, if they’re browsing in the bookstore, why do you think they should invest in your book, and what will it bring to their families?

The book is a beautiful representation of a diaspora that has been historically overlooked and misunderstood. And it was really important for me to showcase, not only the recipes and food we eat, but also why we eat these recipes. It’s a great introduction to this specific community of immigrants, especially with current events. It sheds light on that part of the world and helps people better understand the complexities and nuances that my community still has to navigate and face, but in a way that also celebrates all the different countries and cultures that are represented in the book. And also, all the ways that our shared history has brought us together. It celebrates many different countries and cuisines that have found their way together on one table.

The other thing that sets this book apart from other books, is that with my family being Eastern European, but from the Caucasus, you have this great blend of flavors and techniques from both regions. And so you have a lot of Eastern European and Slavic recipes. You have a lot of recipes from Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan. And then you have this other subset of dishes that combine the two. My family’s borscht has lots of cilantro and chili flakes, which is definitely more of a Georgian accent, our our golubtsy, the stuffed cabbage, has lots of herbs, dill, mint, cilantro, garlic. It’s kind of a fusion of Eastern European flavors with those from the Caucasus. So for those who are interested in those regions, they’ll find it really fun and exciting to cook from the book and to armchair travel to these parts of the world through the recipes.

Do you still have family in Ukraine that you have been worried about?

So when the Soviet Union collapsed, a big chunk of my family made it over to the US, and other family members moved to Moscow. Many of my aunts and uncles lived in Ukraine, many of my cousins lived in Kherson, sort of the South Central region of Ukraine that’s currently being occupied by Russia. I had many family members that have lived there and have since been displaced with the war. Either it was the dam explosion when their lands were flooded, or my uncle’s house had been shelled and burned to the ground. So many of my family members have lost everything and have since fled. It’s really sad to see history repeating itself.

There’s been a lot of worry and tears since the war has broken out. I’ve done a lot of fundraising for my family members, and different nonprofit organizations throughout the country. That’s been really important to me. When there’s so much happening, it’s easy to tune a lot of the news out.

Our largest community is the church in East Providence; the congregation has almost doubled in size since the war. A lot of people from Ukraine and from Russia are leaving a war-torn land. We see a lot of people come from Russia because they don’t agree with the decisions that the regime is making. There’s a second wave of immigration. And at the end of the day, these are all like-minded people that are looking out for each other and are against the war. Even though they have lost everything, we all really care for and look out for each other.

The book is available for pre-order. Publication date is September 16, 2025.

Here’s a sneak peek at one of the recipes:

Penovani Khachapuri recipe. Photo by Dane Tashima.

PENOVANI KHACHAPURI / GEORGIAN FLAKY CHEESE BREAD SERVES 8 TO 10

This sheet-pan version of penovani khachapuri— usually sold as a compact, handheld street food—is made with shatteringly crisp puff pastry and is a nonnegotiable at our big family parties. As the platter hits the table, a bit of a flurry ensues over who gets the corners (or, as we call them, popuchki—“little butts”). Thankfully there’s always enough pieces to go around, corner or no corner, and eventually everyone gets their fill. It’s impossible to get tired of this khachapuri, so don’t be surprised if it becomes a staple in your family, too.

Unsalted butter, for greasing

All-purpose flour, for dusting

One (17.3-ounce / 490 g) box frozen puff pastry, thawed but chilled

1 pound (450 g) low-moisture whole-milk mozzarella cheese, shredded

5 ounces (140 g) feta cheese, grated

5 ounces (140 g) whole-milk ricotta cheese

1 egg, lightly beaten with a pinch of kosher salt

Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C). Lightly grease a 10 × 15-inch (25 × 38 cm) jelly-roll pan or an 11 × 17-inch (28 × 43 cm) glass baking dish or something similar in size. These sizes will give you the best pastry-to-cheese ratio.

On a lightly floured surface, roll out one puff pastry sheet slightly larger than the size of your pan and transfer it to the pan. Sprinkle the moz- zarella in an even layer over the dough, leaving a thin border all around. Evenly crumble the feta cheese over the top. Dollop the ricotta in small spoonfuls all over in an even layer.

Roll out the second piece of dough to the size of your pan and lay it over the cheese. Pinch the edges of the pastry layers together to tightly seal like you really mean it—I go over my pinches a couple of times to make sure there aren’t any gaps. We don’t want any precious cheese ooz-ing out! Then roll the edges up and over the pie and pinch and flatten all over again. Generously brush the pastry with the beaten egg, making sure you get the edges, too. Poke the top of the pastry, save for the edges, all over with a fork— you can’t have too many pokes.

Bake the pie until crisp and golden brown and the bottom is firm, 30 to 35 minutes.

Let cool a bit for the cheese to set before cutting into squares and serving.

Excerpted with permission from Chesnok: Cooking From My Corner of the Diaspora: Recipes from Eastern Europe, The Caucasus, and Central Asia by: Polina Chesnakova published by Hardie Grant North America, September 2025, RRP $35.00 Hardcover.