Four RCTs with a total of 346 participants were included in this systematic review. In two largest RCTs, eGFR was reported to increase following a change to a vegetarian diet (P = 0.01 and P = 0.001). Another two reported no significant differences between the experimental and control groups, and these were associated with a high risk of bias in terms of missing data outcome, or the randomization process. The clinical application of a vegetarian diet in CKD prevention may be compared to a low-protein conventional diet (0.6-0.8 g/kg/day of proteins), due to its naturally low protein character [17] and positive impact on eGFR [17, 18] along with a decreased urinary albumin exertion [20]. In fact, the implemented bias assessment might discredit the aforementioned studies, due to the change in standards over the last 20 years. Therefore, introducing a time criterion for the trials may be the most appropriate solution. Moreover, the study groups in both trials were relatively small, involving no more than 17 patients, which also could have affected the final results. A study strictly comparing the difference between a low protein vegetarian diet and a low protein conventional meat diet was considered biased, thus, the values demonstrated in the study were not significant [19]. Only two studies [17, 18] were assessed, having a low overall risk of bias, and these constituted the basis for the conclusions. There was a significant difference between the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet (VD) and the Mediterranean diet (MD) with a mean difference of 4.2 mL/min/1.73m2 (P < 0.001) in final eGFR. However, considering the eGFR at baseline (0.5 ml/min/1.73m2), the relative final difference is 4.7 ml/min/1.73m2. An increase of 3.4 ml/min/1.73 m² was observed between the initial and final eGFR in the VD group, indicating a positive effect of the diet on eGFR (17). In contrast, among patients following the Mediterranean diet, a decrease in glomerular filtration rate of 1.3 ml/min/1.73m2 was observed. It should be noted that in this study the vegetarian diet was compared to the Mediterranean diet. The Mediterranean diet is high in vegetables and low in protein. It seems promising to conduct a study that will compare the vegetarian diet with the usual diet. In the second study, the authors compared a very low protein (KD) vegetarian diet supplemented with ketoanalogs with a standard low protein (LPD) diet. Glomerular filtration rate decreased in both groups. The KD diet caused a smaller reduction in eGFR than LPD, the difference in eGFR decrease was 4.2 ml/min/1.73 m². Although the eGFR was lower at the end of the study in both study groups, the KD diet helped minimize the decline in filtration function (18).

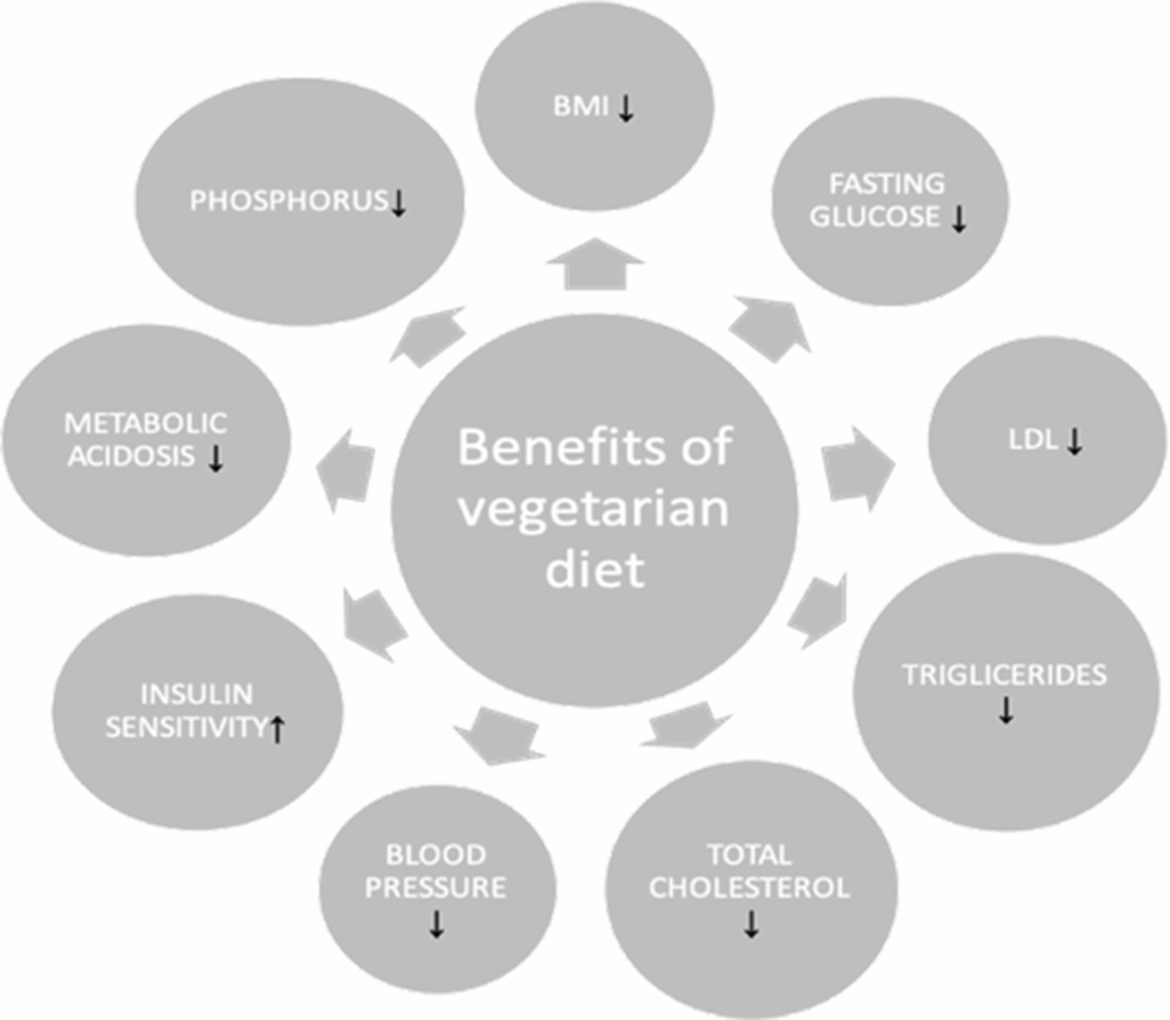

The available scientific sources provide data highlighting other benefits of a vegetarian diet in patients with chronic kidney disease. The crucial aspect is a lower systolic pressure observed in vegetarians, which may have a protective effect not only in terms of the kidneys, but also for the heart. Another vital factor is an anti-inflammatory effects of a plant based diet, which may reduce oxidative stress, protecting against renal injury [22]. Vegetarian diet provides a diversity of a gut microbiome preventing from dysbiosis and low grade inflammation. It can be achieved by the high fiber and vitamin content which increase the bowel transit, preventing from the production of uremic toxins and of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [23]. Vegetarian diet was found to have an anti-inflammatory effect through higher consumption of fruits and vegetables which contain more antioxidative vitamins such as vitamin C, E and beta-carotene [24]. Vegetarians have higher plasma ascorbic acid as well as lower concentration of uric acid and hsCRP [25]. Thanks to this, they have lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease or stroke. Moreover, vegetarians have been found to have lower HO-1 (heme-oxygenase-1) – a marker indicating protective properties against oxidative stress [26]. That constitutes a significant factors in view of the cardiovascular health and the atherosclerosis risk in renal patients. Hyperkalemia, in turn, appears to be a limitation for the prevention of CKD in this group of patients. However, the aforementioned risk is low in patients in stage 4 of CKD, therefore, a vegetarian diet constitutes a safe option for this group [10]. Recent research on the population of CKD patients in stage 4–5 indicated that effects of a very low-protein diet supplemented with ketoanalogues (sVLPD) seem to be as effective as a standard low-protein diet (LPD), with no significant difference in the risk of renal death (P = 0.28) end stage renal disease (ESRD) (P = 0.51), or cardiovascular events (P = 0.2). This provides a new perspective on the idea of the ketoanalogue use in delaying the progression of CKD [27]. In addition to its positive impact on the physical health, a vegetarian diet is considered to positively affect the quality of life (QoL), which comprises several domains, such as physical, social, environmental and psychological. In each of these, vegetarianism plays a vital role in influencing well-being [12]. Although a vegetarian diet seems beneficial, the treatment should be consulted with the dietician to avoid a potential nutritional deficiency.

Although not many RCTs were found, an interesting cohort trial including patients diagnosed with diabetes is worth mentioning. According to a multivariable logistic regression analysis of a cross-sectional study, vegan and ovo-lacto vegetarian diets were found to be less associated with CKD (vegan 0.87, 0.75 to 0.97, P = 0.018; ovo-lacto vegetarian: 0.84, 0.77–0.88, P < 0.001) [28]. Among the patients with a diagnosed T2DM, the risk of CKD was even lower (OR: 0.68, 95% (CI): 0.57– 0.82) in a lacto-ovo vegetarian group as well as (OR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.49–0.94) in the vegan subjects [29]. Moreover, proteinuria was more frequent in the control group (27.7 vs. 21.7% as compared to vegans, and 20.5% in a lacto-ovo vegetarian group, P < 0.001) [29].

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review bears certain limitations. Only papers in English were included in the review, no publications translated into English, or studies published in other languages were considered in the review process, which may lead to language bias. The availability of relevant studies was also a major limitation of this systematic review, as only four studies met the inclusion criteria. The studies analyzed were found to be heterogeneous in various aspects. There were clinical and methodological differences between studies, such as different inclusion criteria, variability in results due to administered medications, and most significantly – different study designs which may have affected the study results. Another factor was the changing risk of bias. Furthermore, the methods of measuring GFR varied between the studies. In terms of the strengths of this systematic review, the risk of bias was assessed using ROB2 tool in the case of each study.