BERRYVILLE — Justin Bogaty has earned a distinction that few in the wine industry ever achieve.

Bogaty is the chief winemaker for the Bogaty Family Wine Group, which operates Veramar Vineyard in Clarke County, the James Charles Winery & Vineyard near Winchester and Bogati Bodega & Winery in Loudoun County.

He recently was recognized for 100 wines he’s produced having earned scores for excellence of 85 points or higher from Wine Enthusiast, one of the nation’s most popular magazines for wine-lovers and connoisseurs.

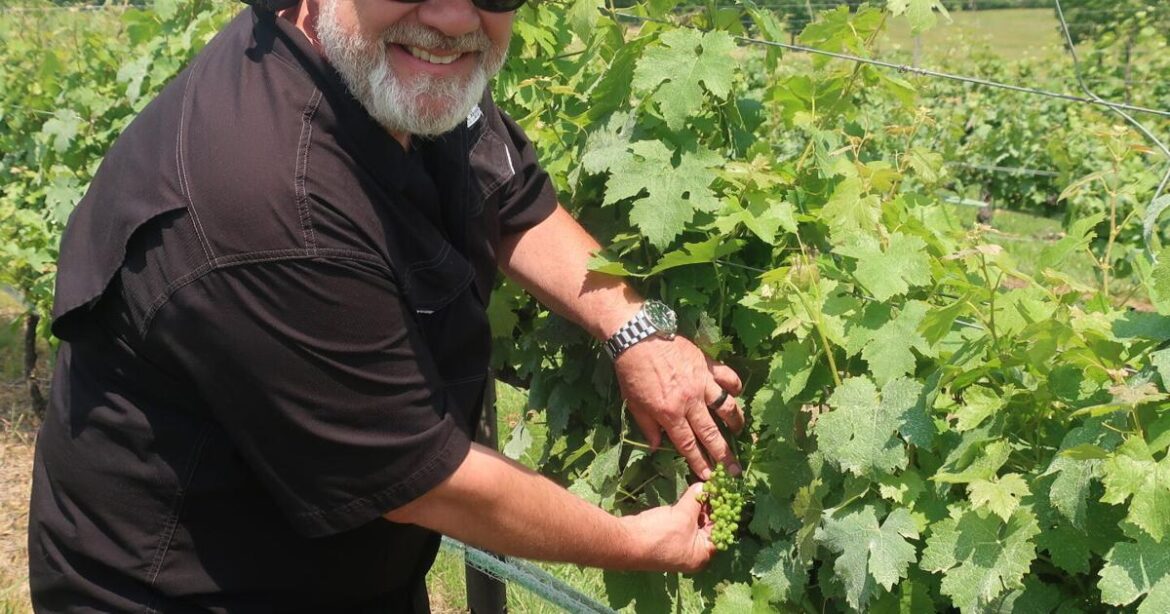

“It feels pretty darn good,” Bogaty said, grinning while standing among grapevines at Veramar.

For those who aren’t familiar with wine-making, he compared his recognition to being told by a top food critic 100 times that your cooking is excellent.

“It’s a huge honor,” he said, “and a sign that you’re one of the best at what you do.”

Receiving 85 or more points for a particular wine means it’s well-made and its quality is above average, Bogaty explained. It shows that a lot of skill and care went into making the wine.

Having 100 wines with such ratings means consistency, he said.

“Getting a few good ratings is nice,” he continued. “But doing it over 100 times means you’re not just lucky. You’re doing something right again and again. It’s not a fluke.”

Bogaty described Wine Enthusiast’s rating system this way: 80-85 is good, 86-90 is outstanding and 91 or higher is superb.

He estimated that 15 to 20 wines he produced scored either 90 or 91, the latter being the highest score he’s earned.

Just a few winemakers have ever received a perfect 100, he said to his knowledge, adding “it’s a rarity.”

Of course, he hopes to achieve absolute perfection someday. But he’s content with his accomplishments so far.

Bogaty’s parents, Jim and Della Bogaty, opened Veramar 25 years ago on approximately 30 acres off Quarry Road east of Berryville, having bought the property a few years earlier. For a hobby, they planted some grapevines. The hobby gradually turned into a business that has grown considerably during the past quarter century.

Veramar remains the family group’s largest vineyard and the headquarters of its operations. Its wines are sold and shipped internationally, although roughly 90% are purchased at the vineyard, Bogaty said.

“I’m pretty proud of that boy to earn that many awards in a little place like Berryville,” Jim Bogaty said of his son.

Justin Bogaty said the recognition by Wine Enthusiast magazine is especially notable because “we’re a small, family-owned winery” in a region where the fermented beverage industry is emerging.

Veramar’s wine-making crew consists of three people — Bogaty, an assistant winemaker and a vineyard worker who manages the grapevines.

That contrasts with much bigger wineries with larger crews in predominant wine-producing regions, such as the Napa and Sonoma valleys in California. Those firms may have 50 to 60 people involved in determining their wines’ quality, Bogaty gauged. They’re more likely to be honored, according to Bogaty, as they produce and submit for consideration numerous wines from different vintages throughout the years.

At Veramar, “we may only submit two or three wines a year” for judging, he said. So “it’s really hard” to compete with them.

Bogaty has been a professional winemaker for 18 years, so he’s learned a lot about fermenting processes and other aspects of the craft.

Experience helps a winemaker determine when a wine is just right for bottling, he indicated.

Nevertheless, “great wines are actually made in the vineyard” with high-quality grapes, Bogaty said.

“You cannot make great wine from bad grapes,” he said. Then again, “you can take great grapes and royally screw up” the wine.

Growing grapes in the Northern Shenandoah Valley is a complex venture because of several factors, he said.

Compared to the California wine valleys, the region is hillier and rockier. And, the soil is extremely old and less fertile, which puts stress on the vines.

“But the more that grapes have to suffer (as they grow), the better the quality of the wine,” said Bogaty.

Too much rain can dilute natural sugars in grapes, which can harm a wine’s flavor profile, he said.

The surrounding mountains help trap moisture, resulting in higher humidity levels.

Generally, “we don’t need irrigation here,” Bogaty said.

“You couldn’t grow grapes in Napa if you weren’t irrigating,” added the University of California at Davis graduate.

Veramar is about a mile from the Shenandoah River.

“This part of the valley was created by the river at some point” in time, Bogaty noted, pointing to large river rocks scattered in the fields. Some remain in the soil, while some have been gathered and moved to various locations.

Sunlight shines on the rocks, generating light and heat that enables grapes to ripen up to two weeks sooner than in other parts of the country, he said.

Overall, making wine requires giving the vintage a lot of attention.

“It’s a lifestyle, a passion,” said Bogaty. “If you don’t have a passion for it, you’re not going to make very good wine.”

Some people enjoy making small batches of wine as a hobby. Don’t try to turn that hobby into a business if you can’t give it the attention it needs, Bogaty advised.

He’s willing. After all, he’s devoted much of his life to it.

“As long as I’m alive, I’ll keep going” at it, Bogaty said.

He anticipates, though, younger members of the family eventually taking over the business.