Food demand dataset

We used five years of household food purchasing data in the Australian NielsenIQ Homescan Dataset (that is, January 2015–December 201935). This longitudinal dataset comprises a panel of approximately 10,000 households in each year who recorded all packaged and unpackaged foods purchased for at-home consumption (that is, from supermarkets, convenience stores and grocers). The panel is broadly representative of the Australian population in terms of geographic distribution, income levels and household sizes36. The sample of households is unbalanced because participation on the panel varied between one and five years. To collect the data, households used a portable barcode scanner to scan product barcodes (for packaged items) and a scanning guide booklet (for unpackaged items such as fresh fruits and vegetables). For each scanned product, panel members manually recorded the price paid and the quantity purchased. NielsenIQ then determined each product’s name, brand, package size (kg or litres) and food category via linkage with a master product dataset. No data were collected on products purchased for consumption outside of the home (for example, from restaurants and cafés).

Households that were flagged by NielsenIQ for containing unreliable purchase information were excluded from the study. For each calendar year, households were flagged if they (1) were not on the panel for the entire 52-week period, (2) did not scan a barcode for at least 26 weeks or (3) did not meet the minimum spend threshold (that is, an average of AU$5 per week).

To account for inflation over the study period, we chose January–March 2019 as the base quarter and adjusted prices in other quarters using the Consumer Price Index for foods37. Additionally, we flagged and excluded all purchases with implausible prices: (1) more than 5 s.d. above the category-level unit value, or (2) more than 5 s.d. above the brand-level unit value within the category.

SES classification

Household SES was categorized using the Index of Relative Social Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics38. This index summarizes the economic and social conditions of households living within a particular area by considering a range of indicators, such as income levels, education levels, employment rates and housing. To maintain household confidentiality, NielsenIQ does not provide the exact IRSAD score of each household, but instead aggregates IRSAD scores into deciles. Using these scores, we classified households into socioeconomic quintiles (that is, Q1 referred to IRSAD deciles 1 and 2 and Q5 referred to IRSAD deciles 9 and 10).

Category selection

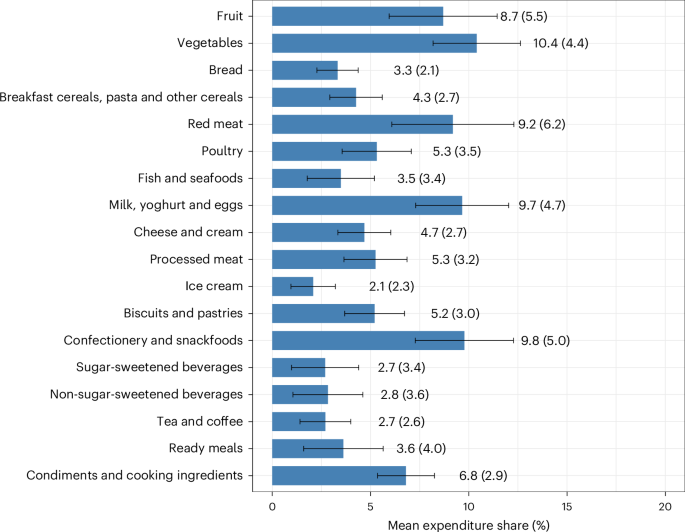

Products were organized into 18 different categories (Supplementary Table 4). The categorization system was adapted from the categorization system used for the WHO Nutrient Profile Model for the Western Pacific and South East Asia Regions39,40. Given that these Nutrient Profile Models were primarily developed to support policies restricting marketing of unhealthy foods towards children, rather than to provide guidance for fiscal policies, we made some adaptations to better align with plausible fiscal policies in Australia. For example, we disaggregated the beverages category into sugar-sweetened beverages, non-sugar-sweetened beverages, and tea and coffee, and also divided the meat category into red meat, poultry, and fish and seafoods. Definitions of each category are provided in Supplementary Table 5. Each category was further classified as ‘core’, ‘discretionary’ or ‘other’ according to the Australian Dietary Guidelines41.

Empirical approach

We used the linearized version of the AIDS developed by Deaton and Muellbauer42 to estimate food price elasticities. This approach has previously been applied to Australian NielsenIQ data to estimate a subset of food price elasticities20,21. In brief, we aggregated transactions annually for each household. Then, the expenditure share of each category (that is, category expenditure divided by total expenditure) was modelled as a function of its price, the price of other categories and the total expenditure.

Estimating category prices

To estimate category prices, one option was to use unit values (that is, category expenditure divided by purchase quantity) for each household in each year. However, unit values may introduce endogeneity into the model because household preferences for quality (omitted variable) can influence both unit values (independent variables) and category expenditure shares (dependent variables). Based on Zhen et al.43 and Sharma et al.20, to reduce this endogeneity bias, we represented category prices using a Fisher Ideal Price Index based on brand-level unit values and quantities, as shown in equation (1):

$${p}_{{jht}}=\sqrt{\frac{{\sum }_{k=1}^{n}{p}_{{kht}}{q}_{k0}}{{\sum }_{k=1}^{n}{p}_{k0}{q}_{k0}}\times \frac{{\sum }_{k=1}^{n}{p}_{{kht}}{q}_{{kht}}}{{\sum }_{k=1}^{n}{p}_{k0}{q}_{{kht}}}}$$

(1)

Here, pjht is the Fisher Ideal Price Index for the jth category for household h in year t, pkht is the unit value of brand k for household h in year t, qkht is the purchase quantity of brand k for household h in year t, pk0 is the mean unit value of the kth brand across all years and households, qk0 is the mean purchase quantity of the kth brand across all years and households, and n is the number of brands.

Wherever households did not purchase a given brand, it was not possible to calculate the corresponding brand unit value. Here, we imputed the brand-level unit value using regression and available brand prices, household size, year and region information, as has been done in prior studies20,43. Additionally, for each category, to reduce the number of imputations, we only considered the top brands that accounted for 80% of sales revenue and combined all other brands into a single group.

Estimating total expenditure

For each household in each year, total expenditure was calculated by summing all food and beverage purchases. However, using total expenditure as an independent variable in the model may introduce endogeneity because it is co-determined with category expenditure shares, thereby representing a simultaneity bias43. To mitigate this bias, we adapted a commonly used approach in the literature20,44 and used the natural logarithm of household annual income divided by the Stone Price Index as an instrumental variable, as shown in equations (2) and (3):

$$\mathrm{ln}\left(\frac{{{\rm{X}}}_{{ht}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}\right)={\lambda }_{1}+{\lambda }_{2}\mathrm{ln}\left(\frac{{I}_{{ht}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}\right)+{\lambda }_{3}\mathrm{ln}\left({H}_{{ht}}\right)+{\tau }_{t}+{R}_{r}+{\nu }_{{ht}}$$

(2)

$$\mathrm{ln}\left({P}_{{ht}}\right)=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{m}{w}_{j{ht}}\mathrm{ln}\left({p}_{j{ht}}\right)$$

(3)

Here, Xht is the total expenditure of household h in year t, Pht is the Stone Price Index for household h in year t, wjht is the expenditure share of the jth major category for household h in year t, Iht is the annual income of household h in year t, Hht is the size of household h in year t, τt is time fixed effects, R is region fixed effects, and νht is the error term.

Demand system

After accounting for price and expenditure endogeneity, the AIDS was estimated using equation (4) below. As part of this demand system, we imposed assumptions that made the demand system consistent with consumer choice, including additionality, symmetry and homogeneity.

$${w}_{{iht}}={\alpha }_{i}+\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{m}{\gamma }_{{ij}}\mathrm{ln}\left({p}_{{jht}}\right)+{\beta }_{i}\mathrm{ln}\widehat{\left(\frac{{X}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}\right)}{\delta }_{i}\ {H}_{{ht}}+{\tau }_{t}+{R}_{r}+{\mu }_{{iht}}$$

(4)

Here, \(\mathrm{ln}\widehat{\left(\frac{{X}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}\right)}\) was predicted using equation (2) and µiht is the error term. Fixed effects were used for household size, year and region. The key parameters to estimate included γij and βi. One expenditure share was dropped during estimation to avoid perfect multicollinearity.

To estimate the Marshallian (uncompensated) price elasticity of major category i in response to price changes for major category j (eij), we used equation (5):

$${e}_{{ij}}=\frac{{\gamma }_{{ij}}-{\beta }_{i}{\overline{w}}_{j}}{\overline{{w}_{i}}}-{\delta }_{{ij}}$$

(5)

In these equations, \(\overline{{w}_{i}}\) and \(\overline{{w}_{j}}\) are the mean expenditure share of the ith and jth category, respectively, and δij is the Kronecker delta (that is, δij = 1 for OPEs where i = j and δij = 0 for CPEs). The delta method was used to estimate standard errors for price elasticities. A two-sided t-test was applied to each price elasticity estimate, and statistical significance was defined as a P-value <0.05 while adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction.

Furthermore, to examine price responsiveness for each socioeconomic quintile, a demand system was estimated separately for each socioeconomic quintile. Throughout, analyses were conducted using R and the micEconAids library.

Robustness checks

Additionally, as a robustness check, we reconducted the empirical approach using three separate inclusion criteria: (1) including households that were flagged by NielsenIQ for containing unreliable purchase information, (2) using a balanced sample (that is, only households that were on the panel across all five years), and (3) limiting to households that made purchases from all 18 categories each year.

We also repeated the analysis using the quadratic version of AIDS, which is a more flexible model that incorporates a quadratic expenditure-share food Engel curve. Because the micEconAids library does not directly support the quadratic version of AIDS, we followed a previous study45 and incorporated the quadratic term as a demand shifter, as shown in equation (6):

$$\begin{array}{l}{w}_{i{ht}}={\alpha }_{i}+{\sum }_{j=1}^{m}{\gamma }_{{ij}}\mathrm{ln}\left({p}_{j{ht}}\right)+{\beta }_{i}\mathrm{ln}\widehat{\left(\frac{{X}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}\right)}+\\{\theta }_{i}\frac{{\left(\mathrm{ln}\widehat{\left(\frac{{X}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}\right)}\right)}^{2}}{{Q}_{{ht}}}+{\delta }_{i}\ {H}_{{ht}}+{\tau }_{t}\,+{R}_{r}+{\mu }_{i{ht}}\end{array}$$

(6)

Here, \({(\mathrm{ln}\widehat{(\frac{{X}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}})})}^{2}\) was predicted using \((\mathrm{ln}(\frac{{I}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}))\) and \({(\mathrm{ln}(\frac{{I}_{{\rm{ht}}}}{{P}_{{ht}}}))}^{2}\) as instrumental variables and Q is the Cobb–Douglas aggregate price defined using \({Q}_{{ht}}={\prod }_{j=1}^{m}{\left({p}_{{jht}}\right)}^{{\beta }_{i}}\) (where βi was estimated using equation (4)).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.