The audience at the Las Vegas convention centre listened intently to the suited British businessman pitching a seemingly irresistible investment opportunity.

The man was James Wellesley, the chief financial officer of Bordeaux Cellars, and he was there to tell them about an unexpected way to make money from the world of fine wines.

“We only lend against investment-grade wine,” Wellesley told his audience at the Sovereign Man conference. “We’re dealing mainly with French bottles, some of the nicer California ones.”

The proposition was an enticing one back in 2017: high returns in an era of record low interest rates.

The American investors gathered in the auditorium could not have known it then, but they would wind up victims of one of the biggest and most ambitious alleged frauds ever to envelop the world of wine.

Wellesley, 58, of Tunbridge Wells, was extradited to New York last week to face charges of wire fraud and money laundering in connection with a $99 million Ponzi‑style scheme. His business partner, Stephen Burton, was arrested and extradited to the US in 2022. Both men have pleaded not guilty.

“The story behind Bordeaux Cellars is a pretty extensive and sordid one,” Don Cornwell, a Los Angeles attorney and “wine detective” who spent years looking into the case, said.

Inspired by a Sunday Times article

Burton, of London, founded Bordeaux Cellars in 2010 as a company trading fine bottles. Wellesley, a childhood friend of Burton’s, joined shortly after.

With banks averse to lending money for such risky investment deals, Bordeaux Cellars found a niche acting as an intermediary between “high net-worth” collectors who needed liquidity to buy rare wines and the investors who provided the money, receiving interest rates as high as 12 per cent in return.

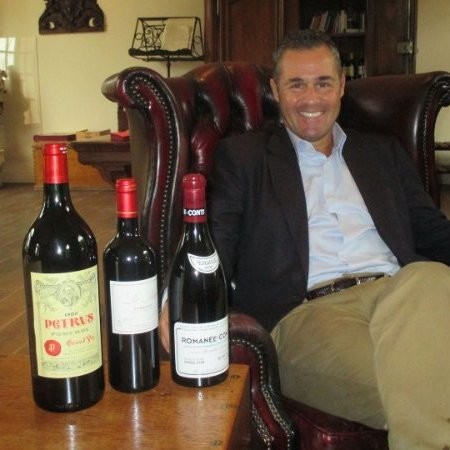

Burton in an image posted online

Burton, 60, claimed to be a Stanford University School of Business graduate who became a wine broker in his twenties.

He told CNBC in 2013 that the idea for Bordeaux Cellars came to him while reading an article in The Sunday Times. “There was a pawnbroker over here in London who had a warehouse full of Aston Martins and Ferraris,” he said. “Literally, people were just driving into this warehouse, handing them the keys for a cash loan. So I just put two and two together, and I thought, you know, we could do this with wine.”

Wellesley, meanwhile, was a disbarred lawyer turned property developer looking for a way to make quick money.

The men told investors the loans would be backed by Bordeaux Cellars’ vast wine inventory, which included bottles worth thousands of dollars from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti in Burgundy and Château Lafleur in Bordeaux. According to a criminal complaint filed over the case, they would receive regular interest payments from the collectors.

Burton and Wellesley claimed Bordeaux Cellars had investors in Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan because those countries offered fairly low interest rates. Burton boasted that he had made more than 200 loans worth more than $30 million and had never experienced a default.

Fooled by the accent?

Burton and Wellesley drummed up business at investment conferences from Las Vegas to Cancún, Mexico. Wellesley would introduce himself using a number of different aliases, including Andrew Fuller, James Anderson and Andrew Templar.

Wellesley explained Bordeaux Cellar’s model at the 2017 Vegas conference: “Lots of our customers now are property developers who are short of cash,” he said.

One investor, a restaurateur who put in several thousand dollars, told The Times: “I was totally convinced. Maybe it was the accent, maybe it was the confidence, but he had me.”

The pair were becoming well-known in wine circles in New York, Hong Kong and London. Burton as the apparent aficionado, Wellesley the business brains. Burton’s LinkedIn profile shows him posing next to an expensive Château Pétrus and claiming to have a private collection of more than 5,000 cases:

Burton’s LinkedIn page

LINKEDIN/STEPHEN BURTON

“Stephen was the guy who would show up with crazy bottles at dinners and try to impress people with his stories,” said Alex Turnbull, then at the London-based wine firm Justerini & Brooks and now head of private and online sales at Jeroboams.

“I once heard him say with great confidence that he had the largest collection of Penfolds Grange [an acclaimed Australian shiraz] in the world. I said to him, ‘funnily enough, I know someone who claims the same, you guys should meet up’.

“He got very defensive and kept making excuses.” Turnbull also claimed Burton spoke with an Australian accent that he thought was affected. “You get a sense very quickly when you share a great wine with someone whether they’re legitimate or not,” he said.

‘They would have disappeared off the face of the earth’

Turnbull’s only professional dealing with Bordeaux Cellars was in 2017, when one of his clients was looking to secure a loan against his $5 million collection. “Bordeaux Cellars agreed to something like 25 per cent loan-to-value, so I think they were paying something high like a million, a million-and-a-half, in cash.”

Alex Turnbull says he saw through Stephen Burton’s braggadocio

JEROBOAMS

Turnbull said Wellesley was insisting the client relabel his collection with Bordeaux Cellar labels, which Turnbull called a “red flag”. He said: “That’s a very important technicality because if a case of wine stored under bond gets relabelled with someone else’s name on it then legally they become the owners of that property, which could become a real problem for the collector.

“James called up and he was very aggressive, issuing all sorts of threats and saying the [relabelling] had to happe. I’m convinced that if we had done it at that moment in time James Wellesley and Stephen Burton would have disappeared off the face of the earth along with all that wine.”

Meanwhile, the restaurateur began to suspect something was amiss when Burton claimed that an American going through a divorce had put up two dozen cases of Screaming Eagle to get “some quick cash”. The investor questioned why a person wealthy enough to own so much of Napa Valley’s priciest cult cabernet sauvignon would agree to loan it at 16 per cent interest.

For the first two years, investors saw regular quarterly interest payments. Then, as the years went on, the payments became fewer and further between.

Arrested on Valentine’s Day

According to legal papers, it is alleged that another American investor handed over $200,000 as a loan for an investment against a collateral of rare wines contained in the Bordeaux Cellars’ warehouse in London, but when he went to check, the wine was not there.

“According to one of the witnesses from the wine trade that I spoke with in the UK, in late 2018 Burton showed up at the storage facilities and used a credit card to pay the duty and VAT on the wines stored in bond there and then took every last bottle with him,” said Cornwell, the Californian wine detective who helped to expose the infamous forger Rudy Kurniawan. The story of Kurniawan’s downfall — and Cornwell’s role in it — was turned into the hit Netflix series Sour Grapes.

• How the world’s biggest wine fraudster could yet make his fortune

The Bordeaux Cellars scheme collapsed in February 2019 when Burton and Wellesley stopped making interest payments to investors altogether. One victim attempted to call the London office on the number given on the Bordeaux Cellars business card, only to be told there was no such firm at that office.

According to legal filings, the wines claimed as collateral for the loans did not, for the most part, exist. The money raised by the new investors had gone to pay interest to the previous ones, and to the two partners.

Burton was arrested in a hotel in Kent on Valentine’s Day, 2019, after a tip-off. In his room, the police found two fake passports, expensive collectors’ watches, gold bars and South African and British currency with a total value of almost £1 million.

Burton was charged in the UK with money laundering and possession of false documents and sentenced to four years in prison. He was released in the summer of 2020 and left the country, just as the FBI began investigating allegations of the fraud.

‘Andrew Templar’ lives a lavish life

Burton and Wellesley were indicted in March 2022 by a grand jury in New York, accused of inducing investors to “invest in excess of approximately $99.4 million in term loans purportedly brokered by Bordeaux Cellars”. The US authorities requested their extradition, alleging that 71 of the 141 victims were based in the US and that they had collectively lost nearly $25 million in the alleged Ponzi scheme.

Burton was arrested again in Morocco in 2022, federal prosecutors say, when he tried to enter the country using a fake Zimbabwean passport, and was then extradited to the US on an FBI warrant.

Wellesley faces up to 20 years in prison if convicted

LEE SORRELL

Wellesley, while working as a solicitor, had been found guilty by a disciplinary tribunal of embezzling funds from his clients’ accounts during the period from 1989 to 1995 totalling £127,000 and was later disbarred. In 2013, Wellesley served jail time for fraud after borrowing £5.7 million for a property scheme involving 19 luxury apartments and failing to repay the loan after the bottom fell out of the market.

Wellesley had kept about £3.5 million of the proceeds, using the money to fund a lavish lifestyle in southeast Asia, where he changed his name to Andrew Templar to avoid detection. He was eventually arrested when he returned to Britain in 2013 to visit his family. He served three years of a six-year sentence, before returning to work at Bordeaux Cellars after his release in 2016.

Wellesley was arrested in 2022 and held at Wandsworth prison until his arraignment at the Brooklyn federal courthouse last Friday. “These are all allegations, and we will defend them vigorously,” John Wallenstein, Burton’s lawyer, said. Wellesley’s lawyer could not be reached for comment.

Trial dates have not yet been set, but both men face up to 20 years in prison if found guilty. Announcing the indictment, Breon Peace, US attorney for the eastern district of New York, said: “Unlike the fine wine they purported to possess, the defendants’ repeated lies to investors did not age well.”