Clement Bouilloux, market expert at Montel, discusses how France’s power system is becoming an overloaded circuit – generating more clean current than the grid can absorb and risking short-circuits of value, not voltage.

I’ll declare my bias up front: I’m French – so naturally, I know better. I’m an engineer – so I really know better. Put those together and you see the problem. But in energy, “knowing better” often means being proven wrong, especially whenever the debate turns to solar versus nuclear. As an engineer, I want an optimal solution. But too often, we treat solar and nuclear as items on a menu – just order both and wait a decade. It’s not so simple. France already runs on nuclear, with 57 operational reactors (59 if you count Fessenheim, which perhaps we shouldn’t have closed – too late now). So, it’s not a matter of “nuclear or solar” but how to fit solar into an already nuclear-heavy system.

Solar in a nuclear world

Nuclear runs flat out, filling most of the baseload need. The residual load during solar hours – the demand not already covered by nuclear – is shrinking. It will drop from about 16 GW in January to 11 GW in May. Installed solar currently totals 23 GW, producing 10-14 GW on a typical sunny day and occasionally spiking up to 18 GW.

You can see the problem: nuclear and solar are exceeding French demand during daylight hours, even before wind or hydropower are added. So, can France just export? Hardly. Across Europe, everyone is installing more solar, creating midday oversupply from Spain to the Netherlands. Interconnectors max out – not from lack of capacity but because nobody wants the excess.

Result? Day-ahead prices crash to zero or even turn negative, with 350 hours of negative pricing in France last year, 457 in the Netherlands and 245 in Spain. This year is on track for even more. Solar was built to be cheap and clean but at scale, it’s now cannibalising its own value. We’re producing more solar than anyone needs – at the same time.

Overproduction: nothing new for France

France is familiar with overcapacity. The 1980s and ’90s saw nuclear likewise oversupply the market – too much supply, too little demand. French reactors learned to ramp flexibly – a rare ability and a key asset today. Pumped hydro storage helps by charging during sunny hours. But it’s not enough: as negative prices mount, French solar – and wind – are being curtailed for economic reasons.

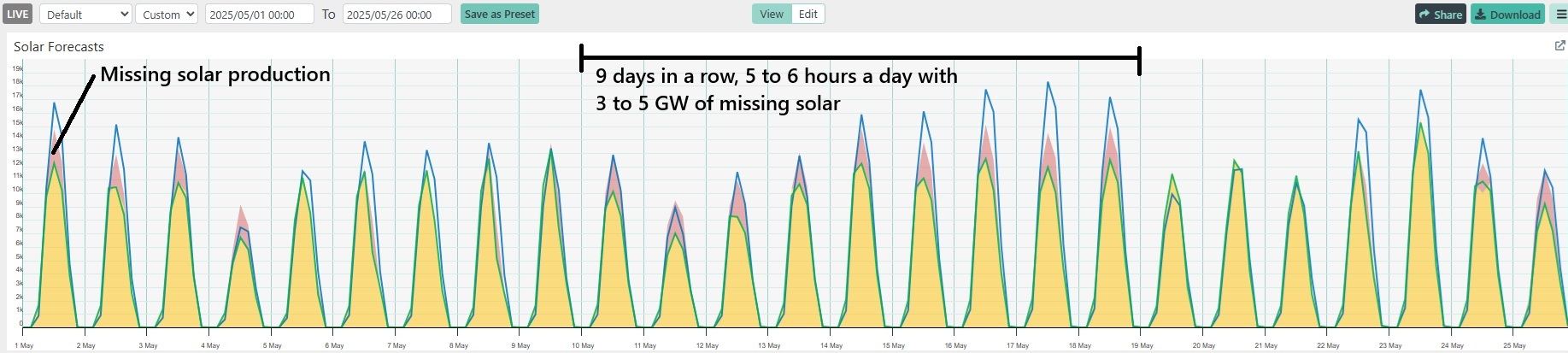

Solar production and curtailment in May 2025. Image Montel Analytics

Solar production and curtailment in May 2025. Image Montel Analytics

In the year to date, more than 500 GWh of French solar could have been produced but wasn’t. If this trend continues, the annual unproduced energy could power a city the size of Strasbourg for a year. That’s wasted energy, investment and emissions savings – and growing proof the system needs more than just a higher number of solar panels.

France is on track for 45 GW of installed solar capacity by 2030, the first step towards 140 GW by 2050. But with current May loads of 46-48 GW, new capacity could outstrip demand – especially given continuing low demand growth. Adding more panels, in today’s system, just means producing the same energy with more hardware. Does it make sense to pour more public money into this, either in France or Europe?

Demand isn’t exploding – yet

Despite all the rhetoric about electrification, French power demand is flatlining. In 2024, total demand is up just 0.7% on last year, still below 2020. Heat pump and electric vehicle sales are falling, while booming elsewhere in Europe. Flagship electrolyser company McPhy has gone bankrupt. Electrolysers were pegged to create substantial power demand to produce renewable hydrogen. The green reindustrialisation dream is colliding with reality.

Policy now turns to “demand response” – incentivising people to use more power when there’s plenty. It’s a big shift from even a few years ago when the official message was to save energy at all costs.

Europe has reached the point where every extra gigawatt deserves scrutiny. The fact remains: we still don’t store power on a seasonal scale. The grid runs on dynamic balance – matching production and consumption in real time. And while engineers like to talk about optimum systems, that only works in a steady state. Today, we’re in transition – risk management, not perfect optimisation, is the need of the hour.

Storage, cars and new demand

Absorbing all this midday excess would take at least 15 GWh of battery storage – about 3 GW charging for five hours. That’s the equivalent energy capacity of 10m fully charging electric cars. By comparison, France currently has 40m cars but only 2m are electric. There’s room for growth.

An electric car charging in Bordeaux, France. Photo: Mikalai Kachanovich/Shutterstock.com

An electric car charging in Bordeaux, France. Photo: Mikalai Kachanovich/Shutterstock.com

Another possible solution for surplus is data centres, which run 24/7 – a good match for nuclear’s consistent output and solar peaks.

An ageing fleet

France’s nuclear fleet, mostly built in one decade, will hit 50 years old by 2030. If oversupply persists, France won’t need to keep every reactor running at all costs: safety, economics and politics will decide. We should be asking: what is our optimum system for the next few decades?

Right now, solar and nuclear together offer clean energy – but also wasted power. Only by tackling demand, storage, cross-border flows and system flexibility head-on can we make every gigawatt count. Until then, even knowing better isn’t enough. Until we redesign the system’s architecture – with more storage, flexible demand and smarter distribution – we’re just pushing electrons into a loop with no real output. Even the most efficient design fails if it doesn’t meet domestic needs.

Dining and Cooking