Poetra.RH/Shutterstock

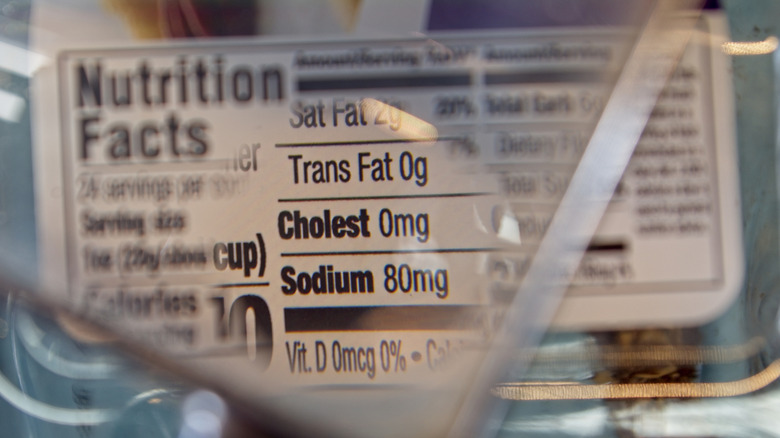

It’s no secret that the marketing world is full of gray areas. Eye-catching descriptors on grocery store labels have an infamous tendency toward ambiguity. Not all canned tuna sold in the U.S. is actually dolphin-safe, even if its label says otherwise, and is it really a good idea to buy clearance-sticker steak? How can consumers help but feel a tad wary? Luckily, when it comes to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) nutrient content labeling, there’s no room for “open to interpretation.”

In order to be labeled as a “good source” of a certain nutrient, per FDA regulation, the product must contain “10-19% of the DV [Daily Value] per RACC [Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed],” according to the National Academies Press. These labels “may be used on main dishes to indicate that the product contains a food that meets the definition, and the food that is the subject of the claim is clearly identified.”

Ranking slightly above “good source” in the FDA labeling hierarchy is the “high” source label. Per FDA regulation, a food item is a “high” source of nutrients if it contains 20% or more of the DV. These quantifiable differences might distinguish a serving of broccoli as “a high source of vitamin D” from a handful of almonds as “a good source of protein,” for example.

A good source must contain a certain percentage of nutrients

Lee Lawson/Getty Images

Unlike the Clif Bar lawsuit, when the energy bar brand was sued for including the word “nutritious” on its packaging, FDA nutrient labels are formulaic and numerically calculated. For instance, if a packaged granola bar were labeled as a “good source” of iron, it would need to contain 1.8-3.42 milligrams of iron per serving. The current FDA daily recommended value for iron intake is 18 milligrams, and 10-19% of 18 milligrams is 1.8-3.42 milligrams. Similarly, the FDA recommends 420 milligrams of magnesium, 28 grams of dietary fiber, 50 grams of protein, and 2,300 milligrams of sodium as the daily values of these other popular nutrients.

The FDA (which is different from the USDA and uses separate regulations) isn’t about marketing products to consumers. The organization is designed to protect public health and safety by providing factual information about the U.S. food supply — even if that transparency is sometimes at odds with exaggerated marketing ploys. To quickly calculate whether a certain food is a “good source” of any particular nutrients, simply divide the total FDA recommended daily value by the listed nutrient content on a product’s nutrition label. If the result falls between 0.1-0.19, then the food item qualifies as a “good source” of that nutrient.

Dining and Cooking