Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

It all began with an opinion piece. In February, I wrote an article for Al Jazeera – a tribute to the doctors in Gaza who were killed or kidnapped by Israel, whose legacy I am hoping to maintain as I go through medical school myself. To my surprise, the piece went viral.

Suddenly, my Instagram inbox was filled with friend requests and messages from people across the world — strangers who wrote to tell me how deeply they were touched, how they stood with me, how they were praying for my safety and future.

Among those messages was one from Dr. Alison Kinning, a vascular surgeon from the United States. I accepted her request and read her words: “A powerfully written piece. I wish you success and safety in your lifetime.”

Uncompromised, uncompromising news

Get reliable, independent news and commentary delivered to your inbox every day.

Dr. Alison Kinning with the author in the courtyard of the European Gaza Hospital in Khan Younis on March 17, 2025.Photo courtesy of Basel, CEO of HHO

Dr. Alison Kinning with the author in the courtyard of the European Gaza Hospital in Khan Younis on March 17, 2025.Photo courtesy of Basel, CEO of HHO

We didn’t continue the conversation after that, but a few weeks later, a message popped up on my phone that stopped me cold: “I will be in Gaza on March 13, 2025, and I would like to present you with my own stethoscope — so you will remember me throughout the rest of your journey in medical school.”

She added: “If you need anything from outside Gaza, I could bring it to you. And if you want me to take something from Gaza to someone in the U.S., I’m willing to do that as well.”

Related Story

Buyers and sellers alike struggle to survive under both siege and constant threat of Israeli airstrikes on the markets.

I sat there, stunned, reading her words over and over. A stethoscope. A gift, a gesture, an offering across the miles. It hit me then — she was coming to Gaza on a medical mission, as a vascular surgeon, to help patients clinging to life. I was overwhelmed by her kindness.

I told her about my sister, Dr. Intimaa Salama Abo Helow — a dentist pursuing her PhD in the U.S. — who had been struggling for months to send us basic medications and vitamins that had long been out of our reach. Dr. Alison offered to help without hesitation, and I connected the two of them while I remained here, in Gaza.

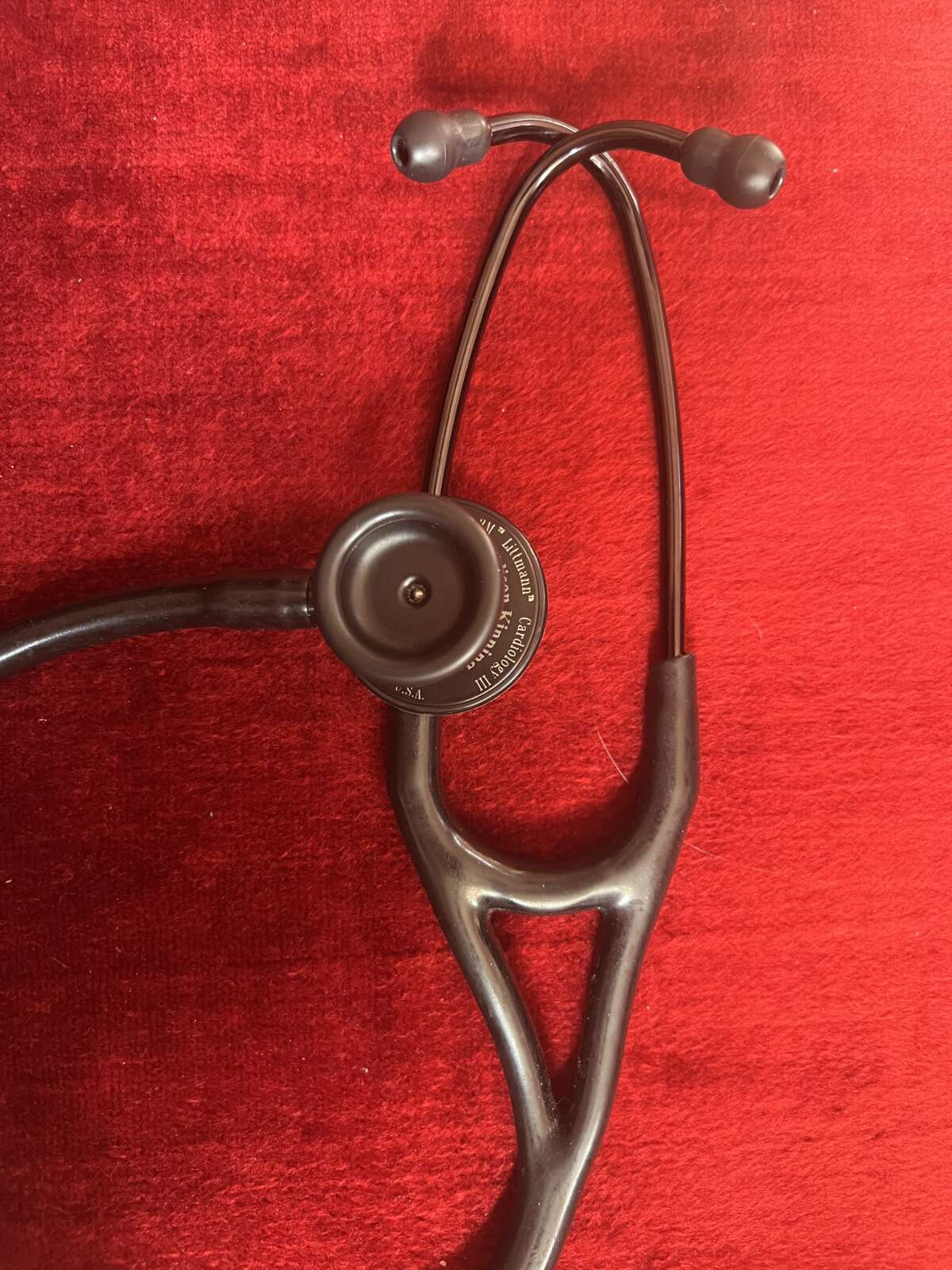

The stethoscope gifted to the author by Dr. Alison Kinning.Photo courtesy of Hend Abo Helow

The stethoscope gifted to the author by Dr. Alison Kinning.Photo courtesy of Hend Abo Helow

Alison kept me updated on every step of her multi-day journey to Gaza, beginning March 10, when she left the U.S. She passed through Jordan, spending the night there before continuing on to occupied Palestine. “It’s my first time visiting the Middle East,” she told me of her medical mission with a team of three other doctors.

On the morning of March 13, they set out for the border, carrying medical equipment that health workers in Gaza’s crumbling hospitals had been pleading for — equipment Israel long denied entry, equipment that could save lives. But most of it was confiscated at the crossing, and they were left with only one bag each. My heart clenched when I heard this. One bag. How tragically, painfully small that was, compared to Gaza’s desperate need.

Despite the deliberate delays by Israeli forces, they reached Gaza by 6 p.m. Alison messaged me as she traveled to the European Hospital: “I was shocked by the scale of destruction and devastation. It’s nothing like what I saw through my phone.”

Alison had come alongside Dr. Siraj, a Libyan-British orthopedic surgeon; Dr. Usama, an Egyptian-British neurosurgeon; and Dr. Ismail, an Indian-British neurosurgeon. Their mission was made possible by the Heroic Heart Organization (HHO), which worked tirelessly to support them.

At the time, it was the holy month of Ramadan — barely two weeks after Gaza had been completely blockaded. Even in these dire times, HHO did everything they could to organize care for these visiting physicians, offering them warmth, shelter, meals, sweets, and drinks that reflected the soul of our culture.

Field visits were arranged too — not to tour monuments of glory, but to witness ruins, alleys, shattered streets, each one a living testament to loss, to endurance, to the human will to survive.

Alison told me how deeply she was moved by the people she met: “Their generosity is humbling,” she said. “I like tea with mint. I also love qatayef — we shared some after Iftar,” she said, referring to the cream or nut stuffed pancakes that are traditional to eat during Ramadan.

The day after she arrived, Alison got to work — surgeries, patient rounds, outpatient clinics. I knew how intense her days were, every hour stretched thin, every moment a chance to save someone teetering on the edge. I asked her gently, “When would it be convenient to meet, when you’re free from surgeries?” We set a date: March 17.

Gifts the author and her family sent to her sister in the U.S. The pockets bear the name of a local shop for embroidered clothes in Gaza.Photo courtesy of Intimaa Abo Helow

Gifts the author and her family sent to her sister in the U.S. The pockets bear the name of a local shop for embroidered clothes in Gaza.Photo courtesy of Intimaa Abo Helow

From the moment we knew she was coming, my parents and I searched for meaningful gifts — something that could speak for Palestine. My mother called an old friend to ask if she could create a handmade embroidered shawl bearing the symbols of our ancestral home, Beersheba. But her friend answered with heartbreak: “Ten days isn’t enough. I need months to complete such a piece.”

Time was running out. So for the first time since October 7, we braved the local market. Drones buzzed overhead, distant booms echoed, but we kept our focus. We scoured the shops, selecting a beautifully crafted jacket for Dr. Alison, another for one of Intimaa’s close friends, a red embroidered keffiyeh for our Jordanian friend, and a white one for Intimaa.

My father carefully held Intimaa’s shawl and sprayed it with his favorite cologne — the scent she loved most. “So she can feel my presence whenever she wears it,” he whispered. I teased, “It’s nearly 6,000 miles between us and Intimaa. The scent won’t stay.”

But my father, determined, reached out to a new friend, Abu Ibrahim. My father got to know Abu Ibrahim while he was displaced nearby where we are, in Al Nuseirat refugee camp. Abo Ibrahim returned to north in the March of Return with hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians in January, after the ceasefire began. My father asked if he could help find vintage Palestinian pieces at Souq al-Zawiyah, a market in Gaza City. The pieces Abo Ibrahim gathered were not just items — they were artifacts carrying stories, memories, defiance. Sadly, he couldn’t make the journey back to the south to bring us these items; Israel had begun intensifying its airstrikes again, violating the fragile truce.

Yet, when an old friend of my father, Abu Mu’adh, heard why my father was searching, he was moved. His wife, a master of embroidery, gathered their most meaningful pieces: “We are trapped by death here in Gaza,” Abu Mu’adh said. “Intimaa deserves these. She will value them. Every stitch tells a story — heals a wound—and leaves behind the promise of a free, beating Palestine.”

And then, my father prepared two final gifts: two bottles, each holding two liters of olive oil. One for Intimaa, one for Alison, along with pickled olives. But this wasn’t ordinary oil. These olives had been picked, pressed, and bottled under the shadow of rockets. Their taste carried a history of survival, of resilience, of trees that had stood for centuries, feeding and shading us through siege and hunger.

On March 17, the 17th day of Ramadan, I got a call from Basel, one of the people who worked at HHO: “I’d like to invite you to join us for Iftar today,” he said warmly. I hesitated. “It’s difficult — it’s a 40-minute trip from here.” But my father immediately offered to come with me, even though he worried he might not remember the route anymore. Gaza’s streets had been erased, reshaped by war.

Basel reassured us. “We can send a car to pick you up.” So after Iftar, we went. My father and the driver fell into heavy conversation about the atrocities they had witnessed. Their words trailed off into a silence so deep, only broken by the whispered prayer: “Thank God, it’s over. May it never return — not even in our nightmares.”

As the car crept through Gaza’s broken skeleton, my father gazed out the window, softly asking, “Where are we now?” He had once known these streets like the back of his hand. Now, the landmarks were gone, swallowed by rubble and ruin.

Inside the car, I was panicking quietly. It had been a year and a half since I’d traveled such a long distance. What used to be ordinary now felt heavy with fear — one of the many invisible wounds left behind after surviving relentless slaughter.

When we arrived at the European Hospital — a place that has itself since been bombed by Israeli forces, leaving 28 dead and dozens wounded — I saw Alison waiting. She handed me a bag with medications, vitamins, and her personal gift: her stethoscope. I gave her the gifts we had prepared.

She beamed with gratitude, saying how excited she was to share the Palestinian olives and olive oil with her family. Alison told me being in Gaza was like a dream. “From a virtual connection to standing face-to-face, here in Gaza — it feels surreal.”

Then I asked the question I had carried in my heart: What brought her to Gaza during the ceasefire, knowing war could break out again at any moment?

She looked at me, her voice steady, “I couldn’t stand by and do nothing.” She couldn’t watch children die while she’s behind a screen, knowing many could be saved if only there was real action and intervention. “This is a crack in our collective humanity,” she told me. “I only wish I could do more.”

She showed me photos of a vigil held by U.S. medical personnel, their signs calling for a ceasefire, for an end to the blockade, for the liberation of Palestine.

“The trauma here,” she said, “the vascular damage — I’ve never seen anything like it in my career. I’ve had to amputate limbs over and over, just to save lives. It’s heartbreaking.”

Alison told me about an eight-year-old boy she had operated on — shot in the ankle by a sniper. His leg was nearly gone. She managed to save it, she told me softly. “We repaired his arteries. It was delicate, but we made it.”

We shared stories, photos, pieces of our worlds. I showed her pictures of our dogs; she told me about hers. We talked about our cultures, our symbols, our shared humanity.

Behind us, my father stood with Dr. Osama, Dr. Siraj, and Mr. Basel. Dr. Ismail stopped by before returning to surgery. Dr. Siraj smiled and asked if I’d like to shadow them in the operating room. Alison introduced me to them, calling me a promising writer and future neurologist, urging them to read my Al Jazeera piece. “It reawakens our moral obligations,” she said.

What touched me in the deepest way was their love, their solidarity, their fierce loyalty to Palestine. They had left behind their families, their careers, their comforts —not for fame, not for thanks, but simply to help Gaza to live, to heal, to be free.

Dr. Osama spoke of a critical case; my father thanked him. Dr. Osama gently replied, “No thanks needed. We owe you more.” Dr. Siraj added, “We are one nation, one pain. None of us is free until Gaza is free.”

Time passed quickly. We shared coffee, ate qatayef, swapped war stories. It was nearly 12:30 a.m. when we left, inviting them for Iftar another day.

We reached the Nuseirat Refugee Camp at 1:20 a.m. The streets, though late, were glowing with Ramadan lanterns. We arrived home at exactly 1:30 a.m. — half an hour before the inferno began. Explosions rained down as Israel broke the fragile ceasefire that had been holding for weeks.

Alison messaged: “Did you reach home safely?” I replied: “Luckily, yes.”

She told me she had jolted awake, terrified, as the hospital hallways filled with casualties and martyrs. The team rushed to the operating room, working endlessly, pausing only for short naps before diving back in.

Alison kept checking on me almost every day. I tried to comfort her, sharing the safety strategies we had perfected over a year and a half under fire — keeping away from windows, crouching in corners under imminent dangers, and staying out of the view of the drones. She, too, tried to assure me, telling me that everything was going to be okay.

Alison and her team left Gaza on March 27. But they were stopped at the Erez crossing, where Israeli soldiers confiscated the olive oil and olives. Alison messaged me, heartbroken: “They took everything. My heart aches, knowing how much your family sacrificed for those gifts.”

It wasn’t just the loss of those bottles. It was a gut punch to our hearts. We had risked everything for that oil — oil that wasn’t a weapon, wasn’t a threat. And yet, they feared it. They feared the presence of our identity, of our history, staining their hands.

They feared the olive trees — the trees that know, more than anyone, who the true owners of this land are.

Later, I came across a study that found that two-thirds of the Israeli public had allergic reactions to Levantine olive pollen, compared to just 14 percent of the Arab population living in the same kinds of areas — people who could likely trace their family’s history back on these olive-rich lands for several generations.

A part of me felt a strange satisfaction. But another part was furious — furious that even when they couldn’t enjoy what they stole, they still took it, just to deny us the comfort of giving.

On April 17, Alison sent Intimaa her gifts from us. Intimaa opened the envelope and finally touched a fragment of Gaza, distributing the gifts to her friends. Yet it was my father’s cologne that stood out most — its scent stronger than everything else, wrapping her in memories, in love.

My father had been right: 6,000 miles couldn’t break an unbreakable bond.

Alison wrote back: “Gaza changed me forever. It left a mark I’ll carry for life.”

Just like Intimaa’s connection to us. Just like our connection to Palestine.

It doesn’t matter if we are inside of Palestine or outside of it. Our homeland is carved into our hearts, stitched into our skin. We carry it, always.

An urgent appeal for your support

Truthout relies on reader support to publish independent journalism, free from political and corporate influence.

Unfortunately, donations are down. At a moment when our journalism is most necessary, we are struggling to meet our operational costs due to worsening political censorship.

Truthout may end this month in the red without additional help, so we’ve launched a fundraiser. We have 48 hours to hit our $25,000 goal. Please make a tax-deductible gift to Truthout at this critical time!

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Dining and Cooking