Sustainability has recently become a central theme in business orientation, in the planning of governments’ strategies and in the motivation of purchasing decision around the globe. Nevertheless, the concept of “sustainability“ is quite complex and broad, having a series of case-specific facets that can be analysed and interpreted from different perspectives (Diesendorf, 2000; Purvis et al., 2019; Kwatraa et al., 2020). Moreover, the well-known (and extremely vague) definition of sustainable development in the Brundtland Report (WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development), 1987; “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”), explicitly links the adjective “sustainable” to economic growth, social equity, food security and natural resources protection. The practical application of this open definition, implying the reconciliation of economics and ecology (despite sharing the same Greek etymological root οἶκος: home/family/family’s properties), still remains the great challenge of the 21st century. One further problem is that while chemical and physical phenomena concerning sustainability are generally quantifiable, the measurement of qualitative data like some social, cultural, environmental and landscape issues (immaterial values) may be subjective (Koo et al., 2009) and can be affected by particular local conditions.

Regarding the Italian olive-oil sector, the extreme fragmentation of the production structure, the different farming systems, the vast national olive germplasm and the prominent economic, cultural (from gastronomy to medicine, from art to mythology and history), social and environmental value of olive, make it difficult to generically define an univocal model of sustainability. The Italian olive sector includes about 825,000 farms (ISMEA—Institute of Services for the Agricultural and Food Market, 2020b), most of them (97%) are sole proprietorships employing about 95% of supply-chain workforce, but generating only 30% of the olive sector turnover (~4.5 billion euros; ISMEA—Institute of Services for the Agricultural and Food Market, 2020a). 81% of the farms have a size of less than 2 ha (55% less than 1 ha) corresponding to 38% of the total olive grove area (Ismea, 2020a). These data are also linked to the hindering orographic situation of olive groves mostly cultivated in hilly (67%) and mountainous (11%) areas (ISTAT—Italian National Institute of Statistics, 2012), where the olive tree represents an integral and characteristic element of the territory as well as one of the few crop options for agriculture and environmental conservation (Tiò, 1996).

Italian olive growing can be generally split between a majority (63%) of nonprofessional small-holder farms and a smaller, but significant, number of professional farms, competitive at the international level (ISMEA—Institute of Services for the Agricultural and Food Market, 2020b). The former represents a traditional, rainfed, poorly mechanized and low input olive growing often practiced in complex orographic contexts, characterized by steep slopes and terraces, in which workforce is provided by family members and olive oil is generally destined for self-consumption (accounting approximately for 4% of the total oil produced). In this sense, these companies have a preeminent environmental, landscape, historical, cultural and anthropological significance, by preserving local traditions and biodiversity (local varieties) and preventing severe soil erosion (Beaufoy, 2001; Loumou and Giourga, 2003; Brunori et al., 2018). From a sustainability point of view, they have a low environmental impact with high social value, but they are generally unprofitable (i.e. they are based on the undervalorization of family worktime), although the earnings are often shared within small communities and families for which they represent an important (if not the only) source of income (Duarte et al., 2008; Palese et al., 2013). Notwithstanding, extensive, rainfed olive groves in dry areas have been forecasted as the most vulnerable to future climate changes (Mairech et al., 2021).

Competitive farms are represented either by small but strongly market-oriented companies with niche productions or by large companies with intensive and in (sporadic cases) super-intensive production systems. These latter systems have been proven to be economically more sustainable than traditional olive groves due to higher yields per hectare and lower operating costs per kg of product (Godini et al., 2011). However, the increase of plant density emphasize the use of agrochemicals, irrigation and mechanization with a consequent greater environmental impact on a per-area basis compared to traditional systems (Beaufoy, 2001; Tous et al., 2014; Russo et al., 2016; Ben Abdallah et al., 2021). Similarly, some studies report a reduction of biodiversity of vascular plants (DRAPAL – Direção regional da agricultura, 2009) and avifauna (Solomou and Sfougaris, 2015; Bouam et al., 2017; Morgado et al., 2020) in response to intensification, as well as a reduction of fish variety and habitat diversity, in water courses in the immediate vicinity of intensive olive groves (Matono et al., 2013). From a social point of view, a direct linkage between intensification and the notion of de-territorialization has been proposed, whereas intensive farming systems are less rooted to traditional knowledges, peculiarities and regional ecologies of the territory and community (Silveira et al., 2018). On the other hand, the carbon sequestration potential of olive orchards has been described to increase under intensification of planting, albeit with some exceptions, because of the greater biomass produced in response to the higher volumes of water employed for irrigation (Mairech et al., 2020). Eventually, in a comparative study on Water Footprint (WF) intensive and superintensive olive orchards had a lower water demand per hectare and lower values for each of the three components of WF, than those recorded in a traditional orchard (Pellegrini et al., 2016).

Italian olive oil industry counts 220 companies and over 4000 olive mills. Therefore, 90% of oil mills process less than 1000 tons of olives, equal to 44% of oil production (ISMEA—Institute of Services for the Agricultural and Food Market, 2020a). On the other hand, the capillary presence of olive mills ensures fast olive processing and therefore the hygienic-nutritional quality of olive oil (given the correct management of the previous phases), as well as the production of many oils linked to the territory. This may represent an additional value especially in tourist areas. Supporting local companies and safeguarding autochthonous cultivars for premium quality products play a great importance for consumers as the on-farm or on- mill purchases account to 26% of the total oil sold in Italy (ISTAT—Italian National Institute of Statistics, 2021). Despite this, since Italy is the world’s leading olive oil importer, “100% Italian” olive oil represents less than 30% of total bottled production (ISMEA—Institute of Services for the Agricultural and Food Market, 2020a). In assessing the sustainability of this “international” oil, the environmental impact due to transport must therefore also be considered. Furthermore, part of this imported olive oil comes from North-African countries with a weaker system of environmental laws (allowing for instance looser use of agrochemicals), than those enforced in Europe. To date, EU trade agreements do not provide particular sustainability requirements for imported goods (Fuchs et al., 2020), insofar as European Commission is about to present a legislative proposal regarding a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), namely a carbon tax applied to imports of certain goods from outside the borders of the European Union.

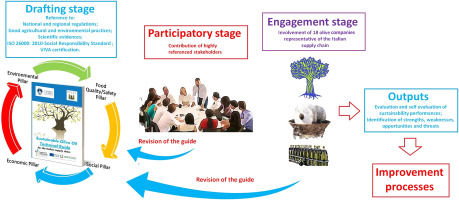

In this scenario, the identification of the high number of variables that must be taken into consideration in the sustainability assessment/self-assessment process for both the agricultural and the processing phases represents a crucial point for a correct definition of actions and policy. The drafting of a “total” sustainability technical guide is part of this perspective, as it was intended as an operational support for the enhancement and promotion of a sustainable olive-oil supply chain by representing a point of reference for olive oil companies in the definition of a sustainability model and in the systematic implementation of improvement processes. At the same time, it can be a useful tool for policy makers to define the areas of economic intervention in supporting olive companies in a context of environmental and cultural heritage protection, premium quality production, fair income distribution, respect for workers’ rights and profitability. Additionally, a sustainability technical guide can represent an aid for small farms in the transition to sustainable forms of agronomic and/or business management in order to access national or European fundings that are traditionally more commonly requested by and granted to large farms.

Dining and Cooking