Drinking wine to the point of ecstasy is something you’ve probably experienced, perhaps in the confinements of your uni halls, perhaps at pub-trips-gone-haywire, perhaps in a field at 3am. We’re not one to judge, and the ancient Roman god Bacchus wouldn’t have either. In fact, he had a whole cult following dedicated to doing just that. So what actually went down at the Bacchanalia rituals, and, importantly, what wine were they drinking?

Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll aren’t a new phenomenon, argues historian Bettany Hughes. Our search for extremity and excess didn’t, in fact, originate in the San Francisco’s ‘Summer of Love’ in the ’60’s, but can be traced right back to the very beginnings of civilisation itself. True, the culture’s come along a bit (ancient civilisations didn’t have Berghain, or progressive psytrance, or even natural wine bars, poor things), but when it came to wine, they didn’t mess around.

Nowhere was this more true than in the worship of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, whose legendary festivals, the Bacchanalia, blurred the line between devotion and debauchery. Drinking wasn’t just as a pastime, but as a full-blown ritual. So who was Bacchus? What really happened at his wild rites? And what were they actually drinking?

Let’s uncork the past.

Who was Bacchus?

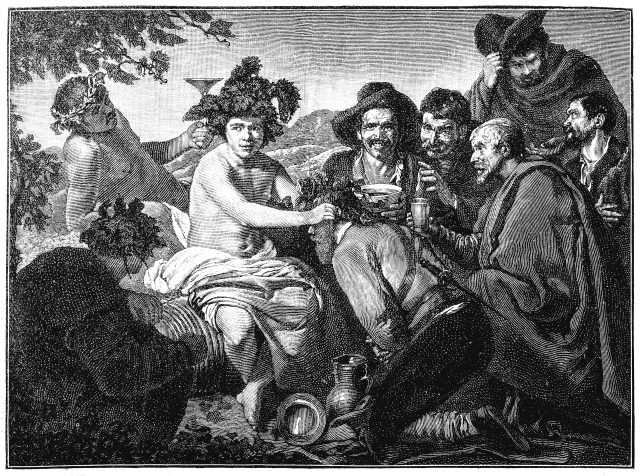

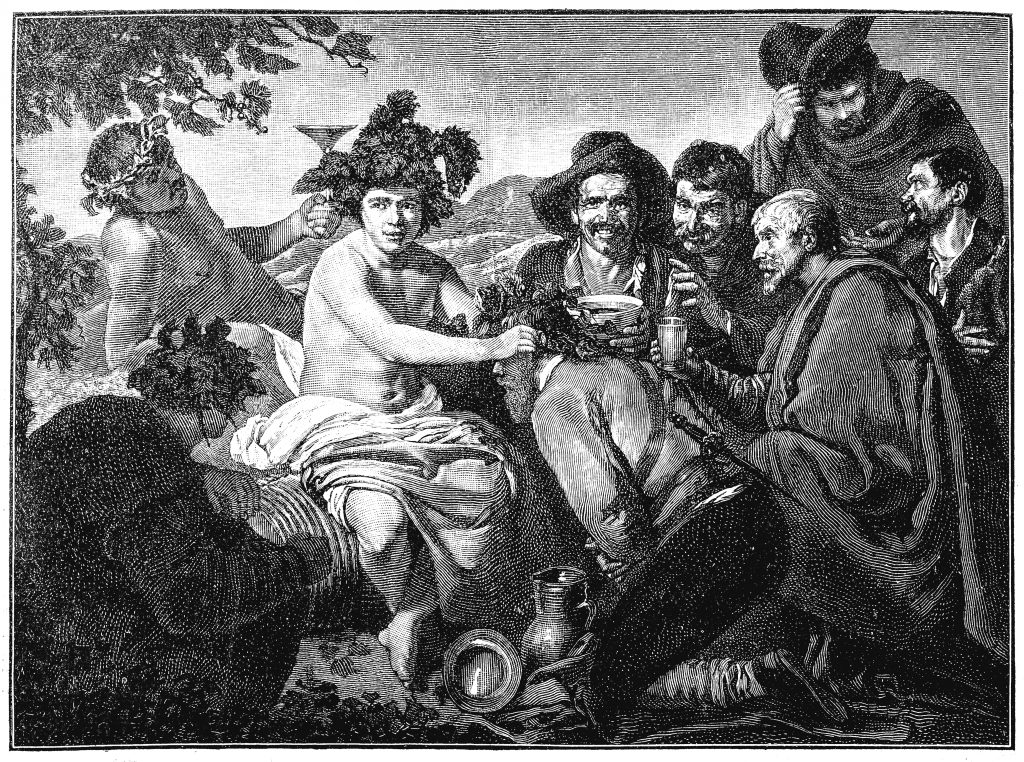

Draped in vines, goblet in hand, and trailed by wild-eyed Satyrs and frenzied Maenads, Bacchus was the Roman god of wine, fertility, and revelry, an iteration of the Greek Dionysus. His name comes from the Greek word bakkheia, describing the ecstatic frenzy he inspired in his followers, a state so intense it was said to be ekstasis, literally ‘standing outside oneself.’

Often depicted as androgynous, Bacchus blurred boundaries—not just between male and female, but between life and death. He promised his devotees a shot at the afterlife, and was sometimes called Dionysus Psilax, ‘he who gives men’s minds wings’. for the transcendental highs he induced. A divine precursor to Red Bull, if you like.

Dionysus is credited with introducing wine to the Greeks, as viticulture swept across the ancient world. Some historians even suggest the Biblical miracle of Jesus turning water into wine was crafted in part to rival the influence of the Dionysian cult. According to myth, grapevines blossomed when Dionysus returned from the underworld. The historian Pausanias reports that, under the god’s power, three empty basins would miraculously fill with wine overnight.

What were his festivals?

Dionysus’ festivals began in ancient Greece as state-sponsored spectacles of worship and release. Tens of thousands gathered—men, women, children, even slaves—to take part in days-long celebrations of music, theatre, trance-dancing, and, of course, wine. Picture ancient raves with flutes, cymbals, wild processions and ecstatic rituals that broke down societal norms.

The Romans later adopted and adapted these events as the Bacchanalia, first recorded around 200 BC. Initially secretive, all-female gatherings held three times a year, the festivals soon expanded to include men and became more frequent, and more unruly. Offerings of wine, grapes and animals were made to Bacchus, alongside frenzied dancing, prayer, and song. In The Bacchae, Euripides describes celebrants wrapped in animal hides, consumed by wild, near-animalistic abandon.

By 186 BC, the revels were deemed so threatening to public order that the Roman Senate cracked down, restricting their size and frequency, and leading in thousands of arrests and executions. Still, some devotees fled to forests and remote groves, continuing their ecstatic rites in secret.

What were people drinking?

At a festival devoted to the god of wine, it’s no surprise that drinking was central. Psychedelic herbs, mushrooms, and hallucinogens like belladonna were reportedly in the mix too, though there wasn’t (yet) a god for those.

Ancient Greek wines were classified as dry, sweet, or sour. “Black wine” (what we’d call red today) was considered the finest, likely due to its ability to withstand oxidation. In The Odyssey, Homer mentions aromatic, sweet black wine. Wine historian Madeline Puckette suggests these wines, concentrated on straw mats, were high in alcohol and sweetness, often with a nutty, brown sugar-like profile.

Wines made from unripe grapes produced sour notes, while varietals like ‘Limnio’, one of Greece’s oldest known grapes, were likely used in both Greek and Roman wines. Drinking vessels ranged from kylixes (shallow cups) to rhytons, horn-shaped goblets designed for ceremonial drinking.

Like the Greeks, Romans diluted their wine with water, often spicing it with saffron, dates, pepper, or honey. But Roman winemaking pushed the envelope: ingredients like pine resin, incense, ash, seawater, and even marble dust were added to alter flavor and texture. Popular Roman blends included passum, a sweet raisin wine, and mulsum, a honey-wine mix likely served warm. The finest wines were said to come from Chios, Lesbos, and Thasos – Greek islands that became legendary for their vineyards. So while we don’t know exactly what the particular pick was for the Bacchanalia, we do know that wine was more than just a drink, but a portal to the wild, frenzied and ecstatic realm of Bacchus.

Related news

Majestic Wine toasts ‘biggest Christmas’ in its history

Snoop Dogg under fire for wine promo during Black History Month

Charting Planeta winery’s modern history through Menfi

Dining and Cooking