In 1985, one of the biggest wine scandals in the world was uncovered: Wineries and bottlers in Austria and Germany had sweetened many millions of litres of wine with the antifreeze glycol and liquid sugar. The consequences were dramatic.

The wine scandal of 1985 triggered the first major debate in modern times about the legally defined safety and guaranteed origin of food. Today we can say that the “mother of all food scandals”, as “Welt” editor Peter Schelling called it in 2010, has changed the world of wine for the better. The understanding of wine as a cultural asset and a high-quality luxury food has changed and developed considerably since then.

The wine scandal was the result of decades of political and economic mismanagement in the Austrian and German wine business. At the beginning of the 1970s, nobody in the Austrian wine industry wanted to admit that wine consumption was declining. The per capita consumption of over 45 litres of wine per year and inhabitant at the beginning of the 1960s declined inexorably. Only the winegrowing politicians refused to accept this and launched major advertising campaigns. They wanted to get more wine down the throats of consumers and thus guarantee greater sales volumes for the wineries. But this did not work. As a result, there was a rapid overproduction of cheap everyday wines, which were bought less and less. Price dumping was the order of the day.

Open doors for the cheats

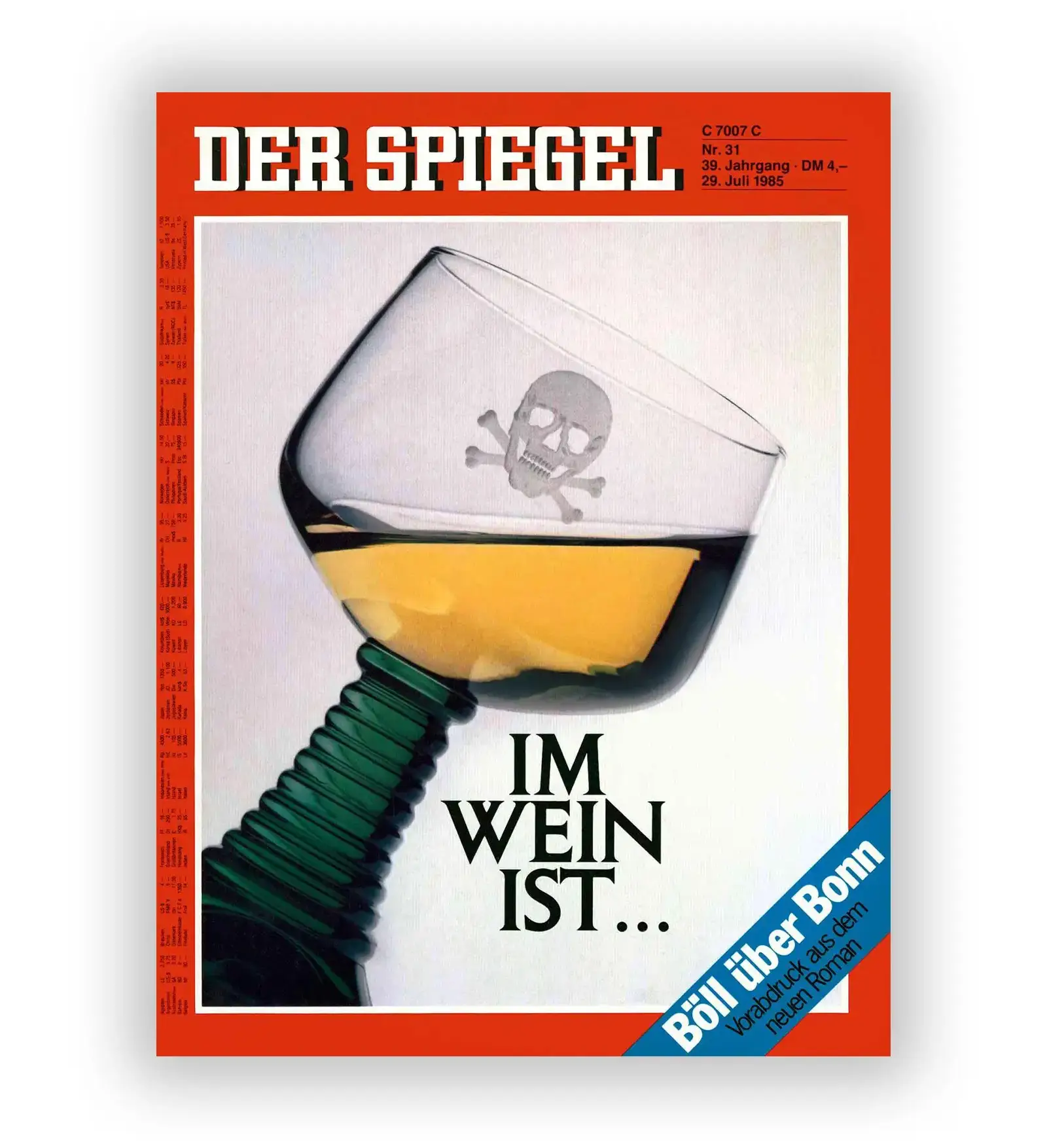

The glycol scandal dominated the headlines in Austria and Germany in the summer of 1985

Der Spiegel

Producers therefore thought about how to raise the price per litre. Austrian winegrowers found the solution in the then unbroken high demand for their Prädikat wines for export. From the mid-1970s onwards, almost the entire production of Austrian Prädikat wines—more than 200,000 hectolitres per year—went to Germany.

This gave some winegrowers an idea: the wines demanded by the German trade could simply be “refined” from the cheapest table wine by adding diethylene glycol to create high-quality Prädikat wines—and sold at good prices. The type of wine in demand was also an invitation to counterfeit as much Prädikat wine as possible. The professional immaturity of the importers and the cluelessness of the wine consumers made it very easy—and risk-free—for the adulterating winegrowers to cheat. Contemporary witnesses also report on this in TV documentaries, which can be seen in the media libraries of ORF, ARD and Arte.

The chemical diethylene glycol, which had previously been used as an antifreeze and for de-icing aeroplanes, was particularly suitable for counterfeiting at the time. This is where the legendary term “Frostschutzauslese” (antifreeze selection) from the magazine “Der Spiegel” in 1985 came from. Diethylene glycol, or glycol for short, was added to Austrian wines to increase the extract values and to pass off inferior table wines as high-class Prädikat wines. Glycol also tastes sweet and full-bodied, which was very much in line with expectations of high residual sugar values. The manipulations remained undetected for years. According to court reports, the adulteration began as early as 1978, with insiders even talking about even earlier years, only these wines had already been drunk.

Scandal in Austria and Germany

The scandal dominated the headlines and news for weeks: One suspected forgery followed the next.

Kleine Zeitung

The scandal began on 21 December 1984 when a whistleblower, who remains anonymous to this day, brought an “adulterated” sample to the Federal Institute of Agriculture and Chemistry in Vienna with a reference to banned ingredients. The chemical detection of glycol in wine at the end of January 1985 marked the beginning of the requiem: on 23 April 1985, Agriculture Minister Günter Haiden (SPÖ) informed the Austrian public about the scandal. It was obvious that the glycol scandal would soon reach the German market and shake its foundations due to the huge export volume. A few weeks after the scandal became known in Austria, it became apparent that massive quantities of the adulterated wines had also reached the Federal Republic of Germany. In the first half of 1985 alone, around 147,000 hectolitres of Austrian wine were imported. A few large German importers, mainly from the federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate, quickly became the focus of investigations. Niederthäler Hof in Rümmelsheim, which belongs to the bottler Ferdinand Pieroth, the Peter Lang and Walter Seidel wineries in Alsheim and the Oster and Mertes wineries in Cochem and Bernkastel-Kues were particularly affected.

The authorities in Rhineland-Palatinate, under the leadership of Agriculture Minister Otto Meyer (CDU) and later Dieter Ziegler (CDU), received the first indications of the forgeries on 25 April 1985. However, they did not act at first. The German government only learned of the glycol findings on 7 May 1985 through a press release from the consumer advice centre. Even the Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry of Viticulture did not begin comprehensive investigations until the beginning of July. When Federal Health Minister Heiner Geißler (CDU) finally officially warned the public on 10 July 1985, the damage had already been done: Many millions of litres of wine were affected, which is why the situation escalated. Countless wines were confiscated in Rhineland-Palatinate and other federal states. From mid-July, the German Federal Ministry of Health sent out long lists of the confiscated glycol wines to trade associations and the media. The tabloid press coverage further fuelled the social panic. One of the media highlights was the headline “Antifreeze wine at grandma’s birthday party—11 poisoned” in the Bild newspaper on 12 July 1985, which turned out to be a “newspaper hoax” but fuelled the economic damage all the more.

The scandal became even more explosive when it became known that quality wines from Rheinhessen had also been illegally blended with Austrian wines contaminated with glycol for years. Again, the Pieroth subsidiary Niederthäler Hof and the Walter Seidel winery were particularly criticised. Initially, those responsible argued that it was “mere contamination of the bottling plants”. However, investigations quickly uncovered systematic blending over a period of years. German wineries had also adulterated huge quantities of wine: between 1974 and 1978, 13 per cent more Prädikat wine was officially tested in the Mosel-Saar-Ruwer wine-growing region and ten per cent more in Rheinhessen than was actually harvested, reported Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) in a review in 2015. One example: according to the report, the Irsch winegrowers’ association on the Saar sold fifteen times the normal yield from the well-known “Ockfener Bockstein” vineyard. The cellar master was later given a prison sentence of two years and two months for cheating.

Dramatic consequences for small wineries

Between 1985 and 1986, Austrian wine exports to the Federal Republic of Germany plummeted by over 90 per cent. German wineries also suffered massively. The small family-run wineries that had no connection to the fraud, but collectively fell into disrepute, were particularly badly affected. At a demonstration in Mainz in August 1985, around 5,000 winegrowers vented their anger and demanded an end to the lax import controls. The banners were worded in clear language: “Helmut Kohl—honorary citizen in Austria. Do the German winegrowers matter to you?” they read, alluding to the Chancellor’s perceived lax reaction. Political consequences followed: in Rhineland-Palatinate, State Secretary Ferdinand Stark was dismissed and a number of senior civil servants had to resign. Minister President Bernhard Vogel (CDU) had to face massive criticism from the opposition in the state parliament. The leader of the opposition SPD party, Rudolf Scharping, accused the government of trivialising and delaying the scandal.

The legal investigation dragged on for over a decade. Around 2,600 criminal proceedings were heard in the 1980s at a specially established wine criminal chamber at the Mainz district court. The investigators gained deep insights into the counterfeiting scene: according to the WDR report, during one court hearing the presiding judge revealed the recipe used by many Moselle winegrowers for years: “Take 1,000 litres of wine and a 50-litre canister of liquid sugar.”

In this way, the criminal court was able to prove that the Schmitt brothers from Longuich (Mosel) had “refined their cellar techniques”. Using more than 600 tonnes of sugar, the wine merchants counterfeited around ten million litres of wine between 1972 and 1980. They produced Spätlese and Auslese wines, even Trockenbeerenauslese wines, from the cheapest table wine. The estimated profit from these counterfeits totalled around ten million marks. On 4 March 1985, Heinzgünter and Gerd Schmitt were sentenced to prison terms of five and four years in the largest German wine adulteration trial to date.

But the investigations continued. The proceedings against the Ferdinand Pieroth winery later attracted particular public attention. Despite allegations that around nine million litres of wine with a market value of 137 million marks (around 70 million euros) had been illegally blended between 1978 and 1985, the trial ended in 1994 with acquittals and fines of around one million marks (around 500,000 euros) due to a lack of demonstrable intent.

Read more:

Dining and Cooking