Michael Patrick Shiels

| For the Lansing State Journal

Wine, cheese, and cuisine – specifically, Lambrusco, Parmigiano Reggiano, and balsamic vinegar – authentically originate in Italy’s Emilia-Romagna Region, known as the “Food Valley” between Bologna and Parma.

Tourists, aficionados, and those seeking edification, go wine tasting in Northern California’s Napa Valley, where they observe the production processes. Similarly, travelers can experience all three of the aforementioned culinary treats, and the resulting magic on menus chefs create with them, by touring Emilia-Romagna’s historic, pastoral Italian countryside.

In 2024, 200,000 tourists visited at least one of the 290 Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese dairies. My visit to the Caseificio San Bernardino’s Parmigiano Reggiano, in Parma, allowed me to see full production of what is known as the “king of cheeses” when I was led through the operation wearing laboratory sanitary scrubs, a hairnet and shoe covers.

I learned Parmigiano Reggiano was created in the 1300’s by traveling monks who noticed something about cow stomachs and enzymes, but I decided it is best not to dive too deep into the details of that discovery. San Bernadino uses no additives or preservatives – just two ingredients: the freshest morning milking and whey. I have “fuzzy math,” but the 100 kilogram balls I saw formed in each of the 20 vats become 40 valuable wheels of cheese-per-day, which means over 14,000 per year. They are then aged for at least a year, and up to 100 months, so the cheese wheels stack up, floor-to-ceiling, and get rotated like wine barrels. And like wine, cow milk from different regions – and length of aging – yield cheese with different aromas, intensities and flavors.

After the tour, I tasted various strengths of Parmigiano Reggiano, which is like nibbling pieces of candy, with dabs of local balsamic vinegar and sips of lambrusco, at a picnic table in the fresh air. Between bites, I chatted with Benedetto Colli, the press officer for the Consortium that protects the cheese and educates the consumer.

“Parmigiano Reggiano can only be produced at the 290 dairies in five provinces in the northern part of Italy – just 10,000 square kilometers,” he said. “I was born in Parma, so I eat it every day. When I was a boy and my mother was cooking, she would always come and give me just a little slice of it so I would grow up strong.”

The taste changes as it ages.

“It is sweet when it starts, and can be paired with prosecco wine. At 24 months it is perfect to be grated over pasta. When it grows older it becomes salty and is better paired with a strong red wine, Irish whiskey, or tequila,” Colli advised.

He said in Emilia-Romagna, when you are speaking of Parmigiano Reggiano, you need only refer to it as “cheese.”

“When you want pecorino or gorgonzola, you call for it by name. Just as in the Veneto area, if you ask for an ‘ombra,’ which literally means a ‘shadow,’ it is local prosecco wine,” Colli explained. “If I had to choose one food to explain to an alien what ‘human food’ is, it would be Parmigiano Reggiano.”

Caseifici Aperti, a weekend “open dairies” festival across the Parma region, is celebrated each April and October.

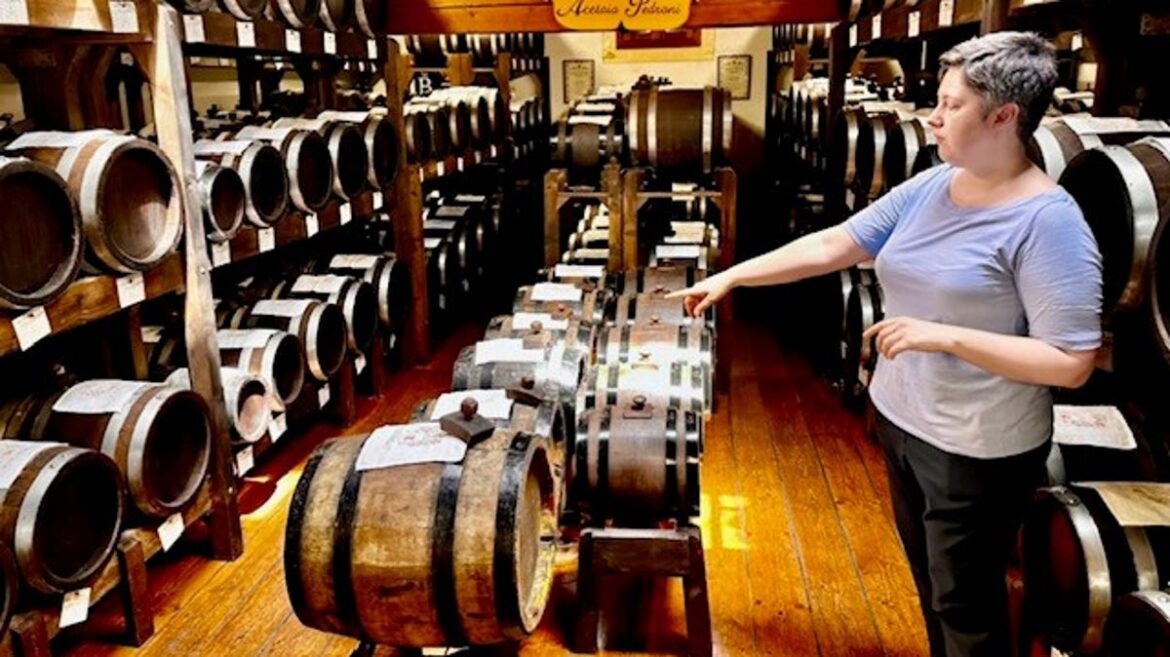

Pedroni Traditional Balsamic of Modena has operated under six generations of family stewardship since 1862. The small, historical campus of buildings, a former monastery, includes a confessional and what was once the village of Rubbiara’s only telephone (1 minute limit.)

After a tasting tour and traditional, artisanal lunch of “tagliatelle” cakes; tortellini; strichetti; and vanilla gelato garnished with 25-year-aged balsamic at Pedroni’s outdoor osteria, Valeria Piccinini and I talked in their tavern.

“In Modena, we are obsessed with balsamic,” she admitted. “To us, it is the most delicious and precious thing in the world. We also have a saying when people get better looking with age, we say, ‘you’re doing as balsamic’ as a compliment since the older balsamic gets, the better tasting and fuller and richer, it becomes.”

Balsamic vinegar of Modena that have an IGP and DOP certification are a treat, since all the region’s producers combined release 100,000 bottles each year. Visitors to Pedroni see, and smell, the fragrant fermentation and pungent aging done in what is called the dynamic method: moving the vinegar through oak and chestnut barrels of different wood and size. Balsamic ends up being sold in traditional (and official) drop-shaped bottles, like perfume, which turn up in gourmet shops, at special occasions and even important business meetings.

The Giacobazzi Lambrusco Museum, outside Modena in Nonantola, is an experience full of whimsy and history: a winemaking tour culminating in tasting the surprising varieties of the local sparkling wine.

“I like hosting the tours here. People are curious,” said Greta Formigoni, serving sips in between popping into the shop to sell bottles. “A lot of people think that Lambrusco is just a sweet wine, but in reality, the most traditional versions for us are dry, because it’s a wine that we are drinking along with a meal.”

The museum also displays sportscars created by founder Antonio Giacobazzi’s friend and fan Enzo Ferrari – and memorabilia for Giacobazzi’s sponsorship of F1 racer Gilles Villeneuve. A statue and photos of the world-famous tenor Luciano Pavarotti depict the Modena’s maestro, also Giacobazzi family friend, enjoying the Lambrusco.

Genuine, Parmigiano Reggiano, balsamic vinegar, and lambrusco come only from Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region. Fly to Bologna for easiest access; there are train stations there, and in Modena, Parma, and throughout the region.

Contact Michael Patrick Shiels at MShiels@aol.com His new book: Travel Tattler – Not So Torrid Tales, may be purchased via Amazon.com Hear his radio talk show on WJIM AM 1240 in Lansing weekdays from 9 am – noon.

Dining and Cooking