The wolf (Canis lupus), because of its adaptability to different environments and its ability to re-colonize territories when no persecution occurs, has in just a few decades expanded its range in Europe (Balciauskas, 2008, Breitenmoser, 1998, Chapron et al., 2003, Chapron et al., 2014). The Russian wolf population is the largest in Europe, supporting those of Baltic and North-European countries, and it is contiguous with the populations of Eastern Europe from which wolves began the re-colonization of Central Europe (Ansorge et al., 2006, Linnell et al., 2005). The Spanish wolf Canis lupus signatus (2200–2300 individuals) is slowly extending its distribution (Mech and Boitani, 2003).

Wolves greatly declined in Italy, surviving in two small isolated subpopulations confined to the southern and central part of the Apennines. At their nadir in the early seventies of the last century, wolves in Italy numbered about 100 individuals (Zimen and Boitani, 1975). Since the late eighties, wolves have shown a spontaneous rapid recovery, re-colonizing all the Apennines and reaching the western Italian and French Alps (Boitani, 2000, Breitenmoser, 1998, Fabbri et al., 2007, Marucco and McIntire, 2010, Valière et al., 2003).

The re-colonization of the Alps would be a fundamental step for wolf conservation in Italy and Central Europe as well (Genovesi, 2002). Moreover, the early and ongoing wolf expansion from the eastern Alps will predictably increase chances to originate mixed packs and increase the local genetic diversity as has been already described (Fabbri et al., 2014, Randi, 2011).

The sub-population of wolves inhabiting the Liguria region thus plays a crucial role in assuring the linkage between the wolves of central Italy and those of the Western Alps (Fabbri et al., 2007). If this link should break, the wolf population of the Western Alps would be isolated, perhaps failing to recolonize the remaining part of the Alps.

The distribution of wolves is usually determined by the abundance of its preys, environmental characteristics, and the risk associated with the presence of humans (Eggermann et al., 2011, Jędrzejewski et al., 2004, Massolo and Meriggi, 1998). This last point is the key problem of wolf conservation because wolves can have a dramatic impact on livestock breeding, affecting human attitudes that can lead to illegal killing, increasing the risk of extinction (Behdarvand et al., 2014, Kovařík et al., 2014).

The impact of wolves on livestock is different according to geographical region. In regions with a very low abundance of wild ungulates, as in Portugal and Greece, wolves feed mainly on livestock (Migli et al., 2005, Papageorgiou et al., 1994, Vos, 2000). On the other hand, in Germany attacks on livestock are rare because shepherds equip the pastures with electric fences to protect their herds and because the wild ungulate availability is high (Ansorge et al., 2006).

In other new-recolonizing areas such as France or North Italy, wild ungulates are the main prey of wolves, but the use of livestock is still noticeable (MEEDDAT–MAP, 2008, Meriggi et al., 2011, Milanesi et al., 2012).

Systematic research on wolf feeding ecology has been carried out since 1987 in the Ligurian Apennines. These studies showed an increasing use of wild ungulates in the time but also a medium–high use of livestock species as prey (Meriggi et al., 1991, Meriggi et al., 1996, Meriggi et al., 2011, Schenone et al., 2004). Consequently, wolf presence in Liguria, as well as in other areas of natural re-colonization, causes a conflict with human populations that perceive predator presence as a negative element that can compromise a poor rural economy. Thus, wolves suffer a high mortality mainly due to illegal killing and accidents. This situation makes the population vulnerable and actions aimed at a greater protection of the species are required.

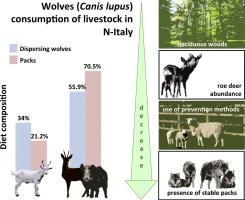

Usually wolf populations are structured in stable packs and lone wolves; packs are formed by a pair of adults, by their offspring and other related individuals (i.e. the offspring of previous years), and sometime by adopted individuals, whereas lone wolves are erratic individuals that can temporarily establish in an area without packs. In general lone wolves are young dispersing from packs but they can also be adults moving far from their original pack because of pack disruption or break off for several causes (killing by humans, low prey availability and related increasing aggressiveness, natural death of the dominant pair) (Mech and Boitani, 2003). Packs are established in areas with high prey availability, because only a high availability of preferred prey can dampen the aggressiveness of the pack members and avoid pack disruption (Thurber and Peterson, 1993). Dispersing and erratic individuals use the areas without wolf packs that can be considered suboptimal habitats because of the low prey availability, high human disturbance, and possibly potential problems with local people (Fritts and Mech, 1981). Illegal killing can break the packs, increasing erratic wolves and reproductive pairs that can have a greater impact in particular on livestock rearing (Wielgus and Peebles, 2014).

The objective of the present study was to determine which factors influence wolf diet, in particular, the choice of livestock as prey, which is the first step to find solutions for wolf conservation. With this aim, we determined wolf diet, by analyses of scats collected in the whole Liguria region from 2008 to 2013. We highlighted the factors influencing it, i.e. years, seasons, ungulate abundance, and social structure of wolves (packs or dispersing individuals). Then we related livestock consumption to environmental features, wild ungulate abundance and diversity, husbandry characteristics, wolf grouping and habitat occupancy behavior (stable packs or dispersing individuals).

Dining and Cooking