On New Year’s Eve in 1995, French president François Mitterrand dined upon the cruel apex of French cuisine—foie gras, three dozen oysters, and a capon. But a smaller bird, the ortolan bunting, was the pièce de résistance of the dying man’s last meal. The sparrow-sized Emberiza hortulana are known as the “soul of France” and are easy to recognize with their olive-grey heads and distinctive yellow eye-rings. Poachers use glue and nets to catch the tiny creatures as they rest in trees after an exhausting migratory flight over the Mediterranean. Sold to restaurants, the captives are blinded or immured, as darkness triggers instinctual gorging. After adding a few grams to their minute frames, they are taken, still alive, and plunged in brandy to drown, then marinate, before being plucked and roasted. Connoisseurs speak rapturously of juices bursting from ruptured organs, of how small bones lacerate the inside of one’s mouth heightening one’s sense of taste. Tradition demands draping one’s head with a napkin to shield this gastronomic atrocity from God’s eyes. Not sated by a single serving, Mitterrand ate two ortolan rôti at his morbid banquet.

It is hard to remember the jubilation following Mitterrand’s victory in 1981—where he became the first socialist president in half a century—and the radical economic program he implemented during his first two years in office, because of the thermidor chill of his later administration and consistent callousness to environmental issues. Any hopes of a green-left alliance sank with the Rainbow Warrior, the Greenpeace ship bombed by French intelligence operatives, in 1985.

Mitterand’s last meal, a symbolic climax of a long-standing contempt towards nature, leads one to ask: how could such an influential politician of the 20th-century European left be a sadistic, vain grotesquerie, when his socialist forebears two centuries prior dreamt of utopias where both humans and animals could be free? It was once natural to ask: why pursue the liberation of just one species if only to raise them as tyrants over all the others? Animal liberation was once a key component of radical politics, but for much of the 20th and 21st centuries it has languished as the “orphan of the left.” For Mitterrand, animals and socialism were only unified in his stomach.

One might assume that animal liberation has returned to the center of radical thought given the flowering of “ecosocialism” over the past decade. In 2016 and 2018, green Marxists Andreas Malm and Kohei Saito respectively garnered the coveted Deutscher Prize—the left’s Pulitzer—and their monographs and manifestos have sold by the hundreds of thousands. The efforts of academic ecosocialists have been reinforced by prominent left-wing journalists, notably Naomi Klein, who shepherded shibboleths such as the “Green New Deal” into mainstream discussions. The contrast between today and the bad old 1990s is profound. Back then, the doyen of Marxist orthodoxy, David Harvey, could unabashedly cite neoliberal dross to buttress his assertion that the “doomsday scenario of the environmentalists is farfetched and improbable,” while Marxism’s premier journal, New Left Review, published drivel questioning the “supposed greenhouse effect.” Before the last decade or so, there were some ecosocialists, but they wrote as individuals—Wolfgang Harich, André Gorz, Ted Benton, James O’Connor, Mike Davis, and so on. Now the tendency has become a collective endeavor at the center of debates. This is all well and good. But where are the animals in ecosocialism?

Here is the intellectual mystery that needs to be explained: why do ecosocialists neglect or outright reject animal liberation? (There are a few exceptions, including Kenneth Fish, Astra Taylor, and Ted Benton, but not many more.) It is astonishing that Verso, the left’s leading publisher, can churn out an endless stream of similar-sounding books on climate change (usually with some variation of “burning” or “fire” in their titles), but have published nothing on the biodiversity crisis and just a smattering on animal rights. (Revealingly, the recent book On Extinction focuses only on human extinction.) Max Ajl and Rob Wallace sound much like spokesmen for a ranchers’ association when they implausibly claim methane emissions from North America’s livestock industry were comparable to the historic bison population, and thus are not worth worrying about. In her review of George Monbiot’s Regenesis in New Left Review, Harriet Friedmann poses the “question of manure” because she cannot imagine farming without livestock, then laments “veganism, even more than conservation” becoming the book’s “driving force,” as if that disqualifies it. The ecosocialists’ flagship magazine, Monthly Review, can publish a critique on conservation for being inherently “colonial” (deploying the Kampfbegriff 17 times in one essay) without displaying any interest in what socialist conservation might look like. In This Changes Everything, Naomi Klein eagerly concurs that “the right is right” when conservatives warn against climate change being a “green Trojan Horse” for the left, but in On Fire she rejects Donald Trump’s extrapolation from the logic of the Green New Deal that “you’re not allowed to own cows anymore” as a “smear.” To adapt the well-known quote from Fredric Jameson, it seems that socialists find it easier to imagine the end of the world than an end to hamburgers.

Such an omission is strange not only because socialists pride themselves on practicing the “ruthless criticism of everything existing,” but because they are descended from a radical tradition overstuffed with vegetarians two centuries ago. Animal liberation was debated and, often, pursued by revolutionary liberals, Romantic poets, and working-class Christians, the troika that would eventually birth the socialist movement. Even after Marxism’s ascendance in the latter half of the 19th century, a few illustrious herbivores remained within the left’s ranks, including George Bernard Shaw, Charlotte Despard, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Henry Salt, Franz Kafka, and Edward Carpenter. How did a coalition of poets, Jacobins, and utopians birth as its descendants ghoulish gluttons and bien pensant theorists who refuse to speak up for another species? When neglect is enough to doom an animal—the ortolan bunting is still heavily poached and will likely perish within a quarter century—then the ethical gap between gorging on songbirds and indifference to their fate is narrow. What happened to the soul of socialism?

For nearly a century, between the publication of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin of Inequality in 1755 and the collapse of Robert Owen’s communal movement in 1845, animal liberation was alongside gender equality, atheism, and abolishing private property among the highest summits of utopian desire. The distant goal of animal liberation and its immediate practice of vegetarianism not only distinguished early socialists from those to their right, but also acted as an adhesive binding various groupuscules of early socialism into a new, cohesive ideology. As we shall see, the animal question would be precisely the point where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels snapped the socialist movement into the camps of “scientific socialists”—as the Marxists arrogantly called themselves—and their superannuated “utopian” predecessors. Once Marxists became the dominant faction within socialism in the late 19th century, the prominent aspiration of animal liberation would fade and be forgotten, except when it would be revived occasionally as an object of ridicule.

Just as Rousseau is a forefather of European socialism without quite being a socialist, he was seen by his contemporaries as a proselytizer of vegetarianism while only dabbling in it himself. He did, however, often discuss animals and meat in his many works. In the Discourse, he argued if one heeded the “inner compulsion of compassion” then one would “never do harm to another man or even to another sentient being.” In Émile, he argued that carnivory changed people’s behavior, and that “great eaters of meat are in general cruel and more ferocious than other men.” As someone who advocated for simplicity in food and other facets of life, he had nothing but contempt for gluttons, who had a “vice of souls that have no solidity” and are “brought into the world but to devour.” It is not hard to imagine what he would have thought of Mitterrand.

Rousseau would inspire many imitators, including British radicals across the Channel. The Scottish vegetarian John Oswald not only admired Rousseau but was inspired by Indian dietary practices during his military service on the subcontinent. Disgusted by colonial violence, he abandoned the British army and rushed to Paris after the outbreak of the revolution to join the Jacobin Club. He soon became a military advisor, an admirer of the guillotine, and an advocate for animal liberation. Amidst the turmoil of the early 1790s, he somehow found the time to pen The Cry of Nature, arguably the first modern pamphlet dedicated to freeing fellow creatures. Oswald’s example inspired other radical liberals, such as Joseph Ritson, who was published by the same press as Thomas Paine. Ritson’s Essay on Abstinence from Animal Food as a Moral Duty was soon accompanied by other vegetarian propaganda, such as Thomas Frank Newton’s inquiry into humanity’s natural diet in Return to Nature. Newton met Percy Bysshe Shelley at the home of William Godwin (another radical liberal and occasional herbivore like Rousseau) to feast on vegetarian fare and radical ideas. Shelley drew on Newton and Ritson when composing his long poem Queen Mab, whose influences are especially evident in the section “A Vindication of Natural Diet.” For Shelley, socialism was inseparable from vegetarianism, hence his denunciation of “the monopolising eater of animal flesh” for “devouring an acre at a meal.” Queen Mab became a tract beloved by working-class radicals, such as the Chartists fighting for universal male suffrage in the mid-19th century. Indeed, George Bernard Shaw recalled being told in his youth by an elderly activist that Queen Mab was known as the “Chartists’ Bible.”

Christians belonging to “dissenting” denominations (i.e., not the Church of England), were more receptive to the swift undercurrent in their religion that pulled them towards socialism and vegetarianism. (This ancient tendency has emerged sporadically since the beginning of Christianity, such as the first-century Gnostics and the mediaeval Cathars, who were vegetarian anti-establishmentarians par excellence).The founder of the conservative Methodist church, John Wesley, was vegetarian. Thomas Tyron, a 17th-century proponent of animal liberation and influence on later writers like Ritson, was Anabaptist. The most important vegetarian Christian for our narrative, however, was William Cowherd, who founded his own church in Salford in 1809 to practice vegetarianism without interference from skeptical carnivores higher up in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Cowherd, who later participated in the founding of the Vegetarian Society in 1847, organized educational programs, communal meals, and scientific training for his working-class congregants, contributing to what one historian called the era’s “proletarian enlightenment.” One Cowherdite, Joseph Brotherton, was active within the labor movement and organized donations for victims of the Peterloo massacre in 1819, when soldiers attacked working-class demonstrators demanding suffrage. After parliamentary reform in 1832, Brotherton was elected as Salford’s first Member of Parliament. Robert Owen, the entrepreneur and utopian socialist, was a Methodist before adopting spiritualism in his defeated old age. He was not vegetarian, but many in his movement were, including William Thompson, his right-hand man and the group’s leading economic theorist.

For these three groups—radical liberals, Romantics, and working-class Christians—vegetarianism was a corollary of their interest in a profound question: what were humans like before civilization? Whether they were atheist or religious, they all believed that civilization had bred squalor, hierarchy, ill health, and alienation from nature. The goal of socialism then was to restore humanity to its natural state, even if people could not actually return to the Garden of Eden or to a life of hunting and gathering. Thus, a meatless diet, holding property in common, and allowing men and women to relate to each other without shame or domination were practical ways to create an earthly paradise. Vegetarianism was a crucial practice to realize this endeavor. Cowherd composed vegetarian hymns for his congregants (“Ours is the food that Eden knew / Ere our first parents fell”), while Rousseau considered it “proof that the taste for meat is not natural to Man is the indifference children have to such food and their preference for all kinds of the vegetarian vittles.”

Shelley and fellow Romantics interpreted the myth of Prometheus as a description of the ancient shift from a herbivorous to carnivorous diet after the adoption of “fire to culinary purposes” which made flesh palatable (“screening from his disgust the horrors of the shambles”). Few of these vegetarian radicals were solipsistically concerned with health alone. Rather, they were moved by the more profound injury of our separation from fellow creatures. In Queen Mab, Shelley looked forward to when:

No longer now the winged inhabitants,

That in the woods their sweet lives sign away,

Flee from the form of man; but gather round,

And prune their sunny feathers on the hands

Which little children stretch in friendly sport

Towards these dreadless partners of their play.

All things are void of terror: man has lost

His terrible prerogative, and stands

An equal amidst equals

Compared to utopian socialism’s verdant intellectual history that teems with animals, Marx and Engels’ collected works offer only a few piffling fragments that could be cobbled together as environmental frameworks. The fruit of such scholarship, Saito’s “degrowth communism” and John Bellamy Foster’s “metabolic rift,” has licensed Marxists to finally care about environmental issues, and thus has its merits. Yet, if the limiting factor in Marxists’ interest in nature is the concern Marx himself showed about soil fertility, then such scholarship offers quite arid ground for a new ecosocialism. Nowhere in Marx’s writings can one find any interest in fostering a new socialist subject who could relate to nature differently, let alone someone akin to Shelley’s edenic human whom animals would not fear. Instead of trying to find validation for ecosocialism solely in Marxism, it is worthwhile to examine the utopian socialist tradition for inspiration and to also see why Marx and Engels discarded the long-held aim of animal liberation as they devised a new socialist lineage. Animals were once at the center of socialist thought, then they suddenly disappeared.

Explaining this rupture requires attending to Marxism’s contradictory place in the history of the left as both an heir of utopian socialism and its usurper. To different degrees, both Marx and Engels praised utopian socialists, drew on many of their goals and concepts, and participated in their organizations. The widespread misconception on the left today that they simply dismissed utopian socialism fails to capture their complicated engagement with it.

Marx and Engels’ deference to utopian socialism—especially Owenism—stemmed from that tradition’s stature as the left’s towering, then suddenly tottering, edifice during their youth. Engels first encountered the left in 1842 when he attended a lecture at an Owenite Hall of Science, a massive building in central Manchester that could accommodate an audience of 3,000. Soon thereafter, he began writing for the Northern Star, an Owenite newspaper, which was part of a publishing empire able to print two million pamphlets a year. While a young Marx was immersed in the political triangle between Cologne, Brussels, and Paris, and thus was far from Owenism’s heartlands in northern England, he felt obligated to attend Owen’s 80th birthday celebration in 1851. He reported back to Engels that “the old man was ironical and endearing.” Even in the polemical Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Engels asserted how “proud” he was to have “descended” from Owen and other utopian socialists. Marx not only considered Shelley to belong to the “advanced guard of Socialism,” but angrily defended utopian socialists from the “coarse insults” of his rival Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Marx and Engels’ proximity to the utopian socialists was not only physical but also intellectual, as they borrowed several key concepts, such as the goal of overcoming the division of town and country, as well as imagining socialist governance in terms of the “withering” of the state.

Marxism would come to surpass utopian socialism, not because of the broadsides fired by the Rheinlanders but from its own charming admixture of hubris and naïveté. There were many intentional communities in the first half of the 19th century in North and South America, the Caribbean, and Europe. The willingness of utopian socialists to try to practice and realize their visions was simultaneously a strength and weakness of the movement. Robert Owen bought 30,000 acres from an existing religious community in Indiana for one experimental community, renamed New Harmony. Its collapse in 1828 cost the wealthy entrepreneur four-fifths of his fortune. When Owen’s last attempt to organize a socialist community, Queenwood, collapsed in 1845, his movement was dragged down with it. Through this yawning gap Marx and Engels stepped in, determined not to repeat the mistakes of the old left. Commentators over the years have suggested various differences between utopian and scientific socialists (e.g., writing “blueprints” and “recipes for the cookshops of the future”), but they have overlooked the most profound point of contention: their opposing conceptions of the human, which in turn affected how each group approached the animal question.

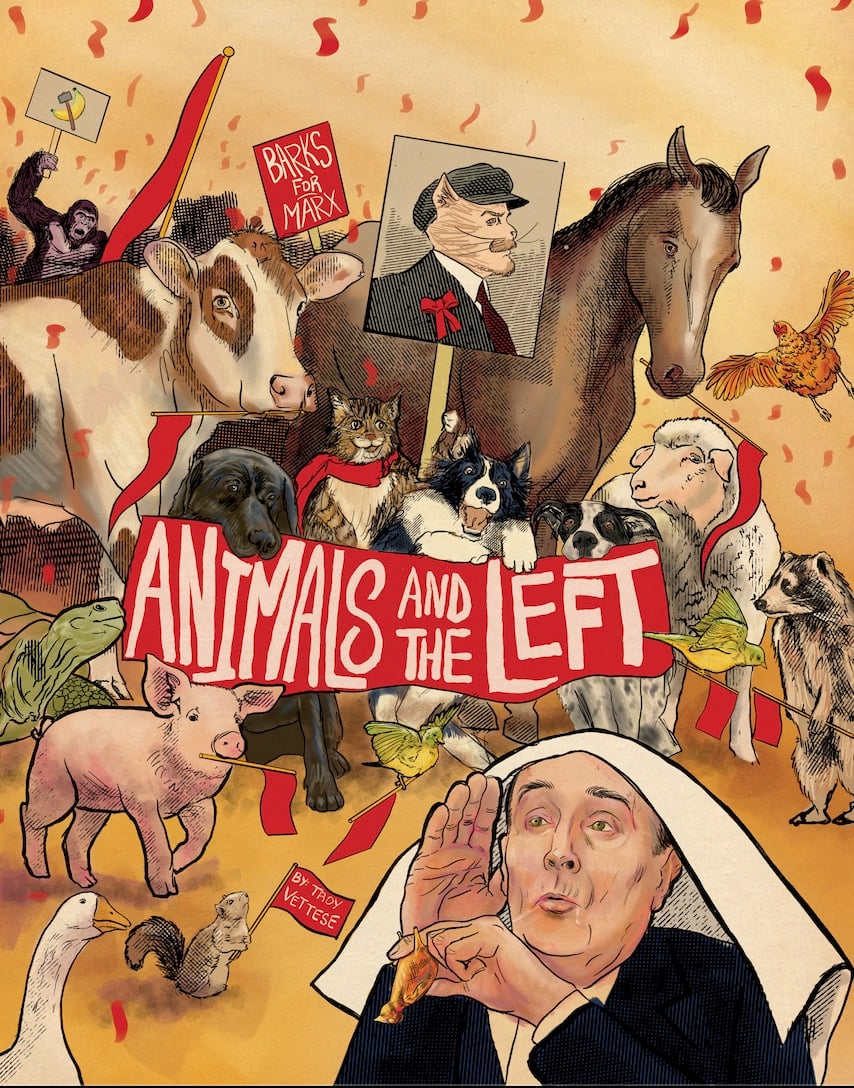

Illustration by Jesse Rubenfeld

Illustration by Jesse Rubenfeld

The differences between utopian socialists and Marxists were ultimately rooted in contrasting conceptions of the human animal. Owen and his fellow utopian socialists assumed that human nature could be understood through study and modified through education because its essence was largely static and knowable. The route to such comprehension could, depending on the kind of utopian socialist, lead through theology, sociology, or anthropology, but they believed that once the facade of civilization was stripped away then our species’ original nature could be discerned in the “savage” or denizen of Eden. Already by the 18th century, early socialists believed that they knew enough about human nature to imagine the contours of a new society. These speculations tended to be rustically Rousseauan: simple clothing, simple food, and simple pleasures. The utopian socialists agreed that, before civilization, humans shared the Earth in common, without any hierarchy (apart, perhaps, from one based on age) predicated on class or gender. Some socialist utopias had some modern conveniences, such as John Adolphus Etzler’s fantastical “naval automaton” powered by the tides or the “force barges” of William Morris’s News from Nowhere, but in the words of one historian, the future would in socialism would be “a bit dull.” Human desires could be known and satisfied: hence the energetic writing of extremely detailed and largely static utopias.

Notably, the utopian socialists’ conception of the human offered little obstacle between Homo sapiens and other species. Rousseau once argued that “every animal has ideas since it has senses […] there is more difference between this man and that man than between this man and that animal.” Once one began to imagine liberation for our species there seemed little reason to stop there, which is why animal liberation appears so early and often in early socialist works. Admittedly, the utopian socialists lacked any understanding of ecology, and therefore the aim was not wilderness but a garden, preferably one where all the animals enjoyed harmonious relations amongst themselves too. In Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s utopia without men, socialist Amazons selectively bred cats so that they lost their instinct to birds, while the beautiful forest surrounding Herland had been denuded of predators. One can find similar examples in other utopian socialist tracts; in some speculations carnivorous animals were replaced with better, benign creatures, such as Charles Fourier’s “anti-lion.” From a contemporary ecosocialist perspective that focuses on the catastrophe of the Sixth Extinction and the potential of rewilding (especially through reintroducing apex predators), clearly one cannot borrow wholecloth from the utopian socialist tradition.

For Marx, however, humanity’s essence or “species-being” was defined by its historicity, consciousness, and unpredictability. In these ways, Marx distinguished humans from a typical animal that was merely “one with its life activity.” For him, animals were unthinking, unchanging, and defined by certain behaviors and organs, while humans thought before they acted, and could become a uniquely “universal” species by treating “all nature [as humanity’s] inorganic body”—that is, as a set of external, mutable organs in the form of tools and infrastructure. This process was, first, historical because human nature would change as people changed their environment and, second, unpredictably dynamic. Thus, detailed utopian blueprints were moot because future desires and abilities would be permanently in flux. This process of changing one’s species-being was a conscious process, making humanity a species uniquely able to direct its own development.

Unlike the utopian socialists, Marx drew not on theology or anthropology, but rather a philosophy of history that convinced him that the “elements of the new society” could be glimpsed in the old and would hint at future developments. As humans were dynamic by nature, Marx and Engels reasoned, our species would change even faster under socialism. Engels also projected Marx’s philosophy of history backwards to argue that humans guided their own evolution through tool-use (increasing the dexterity of our hands) and carnivory (which gave the brain a “far richer flow of the materials necessary for its nourishment and development.”) To emphasize his disagreement with earlier edenic socialists, Engels declared that “with all due respect to the vegetarians, man did not come into existence without a meat diet.” In this conception, humanity was not only different from all other species in that it consciously creates itself, but to realize its species-being it must become a universal animal by redirecting all of nature to its ends. It is not hard to see how this conception of the human would come to undergird Marxism’s nigh indestructible anti-animal bigotry.

The effects of the Marxist view of human nature were detectable soon enough. Whereas vegetarianism remained present in the non-Marxist socialist lineages remaining after the collapse of Owenism in 1845, there have been remarkably few Marxist vegetarians. Shaw saw the new split as “those who want to sit amongst the daisies and those who organize the dockworkers.” One of Marx’s early champions in Britain, H.M. Hyndman, visited one such vegetarian socialist (Henry Salt) and wrote to another (Shaw) to complain:

I do not want the movement to become a depository of old cranks, humanitarians, vegetarians, anti-vivisectionists and anti-vaccinationists, arty-crafties and all the rest of them. We are scientific socialists and have no room for sentimentalists.

During the Russian Civil War, Leon Trotsky summoned the ghosts of the old left to dismiss criticism of his ruthless methods (“Kantian-priestly and vegetarian-Quaker prattle”). In the 1930s, Marxist archaeologist Gordon Childe drew on Marx and Engels’ conception of the human to structure his influential history of the Neolithic Era, in the aptly titled Man Makes Himself. Whereas animals evolve to “better adapted for survival, more fitted to obtain food and shelter,” he wrote, “human history reveals man creating new industries and new economies that have furthered the increase of human species and thereby vindicated its enhanced fitness.” It is unsurprising that the myth of “man the hunter” was coined by another Marxist anthropologist in the 1960s.

These misconceptions seem to have endured and proliferated even after Marxism’s decline in the 1990s, becoming common sense within the broader communities of academic science (e.g., the “expensive tissue hypothesis”) and popular culture (e.g., the manospheric “lion diet”). This Marxist view of human nature has even influenced the conception of the Anthropocene. In a prominent article belonging to that oeuvre, bourgeois environmental historians and Earth-system scientists claim that “the shift from a primarily vegetarian diet to an omnivorous diet triggered a fundamental shift in the physical and mental capabilities of early humans.” Anthropoid egotism likely undergirds contemporary ecosocialists’ focus overwhelmingly on climate change because this crisis imperils humans, while factory farming and biodiversity loss matter only for animals. There are, of course, self-interested reasons to worry about such matters—zoonotic pandemics such as SARS-CoV-2 or avian flu spring from razed rainforests, poaching, and the breadth of animal husbandry from the pastoral to hyper-industrial. A more profound reason to care about animal liberation is for the soul of socialism. When socialists argue for omnivory, they unconsciously adopt a conservative rhetoric that appeals to tradition, status quo, pseudo-science, and vae victis. One wonders if ecosocialists today fear the ridicule of their comrades for being sentimental cranks, for wanting to sit amongst the daisies.

Utopian socialists questioned civilization and imagined socialism as a way to create a new society allowing us to live in a way more fitting to our nature. Marxists, by contrast, do not engage in a civilizational critique. Rather, they want to accelerate and deepen the pace of civilization by realizing our species-being as the universal entity infusing the planet with our consciousness, to fully de-animalize ourselves. Their faith that the new society is being created in utero within the old ironically robs us of our ability to consciously deliberate what kind of creature we want to be, how we want to relate to each other, and how we should relate to the rest of nature. Mitterrand was the paragon of too much civilization, of when a surfeit of sophistication becomes worse than barbarism. Decades later, most Marxists seem unable to perceive the horror latent in their vision of communism, of humanity liberated from capital only to enslave the countless co-inhabitants of our planet.

A new ecosocialism could keep within its theoretical panoply a Marxist critique of political economy, but abjure its nightmarish human-chauvinism. It is bizarre that Marx, the ardent materialist, became an idealist—that is, holding the belief that ideas rather than material conditions drive history—only when he wanted to elevate the “conscious” human over the unthinking animal.1 “What distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees,” he claimed in Capital, “is that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality.” One could quibble with Marx’s grasp of archeology, ethology, and evolutionary biology, but what matters more is that the utopian socialist conception of the human and its corollary of animal liberation is more useful for us now in this era of environmental catastrophe.

Of course, we cannot return to our edenic origins. The hunter-gatherer idyll was only feasible when we numbered four million some 10,000 years ago, not our eight billion today. However, utopian socialism is more feasible than Marxism because it imagines a post-capitalist society that does not depend on completely dominating nature, implementing full automation, and somehow instituting a complex, libertarian social order at a global scale. Marxists somehow still believe that such a society could spontaneously emerge after a revolution and thus not require any discussion on how it would function beforehand. The utopian striving toward Eden while not being able to return creates a different relationship to history, of a thoughtful reflection on our past and animality without degrading into reactionary nostalgia or adhering to a meaningless acceleration into a future. A utopian socialist conception of the human opens up the rigid divide between us and other animals, reminding us that liberation means creating the conditions for us to return to our natural selves.

This goal never completely disappeared on the left. A marginal stream of thought has long meandered slowly and quietly away from the mighty river of anthropocentric Marxism. Theodor Adorno despised the way the “image of the unrestricted, energetic, creative human being has been infiltrated by the commodity fetishism” and instead yearned for a society where one could live “rien faire comme une bête [doing nothing, like an animal], lying on the water and look peacefully into the heavens.” Becoming animals again would include meaningful work, a restored biosphere, harmonious relations with other creatures, and plenty of time for music, love-making, art, and doing nothing at all. It may sound utopian for humans to become beasts again, but is it not more unrealistic to stretch human nature to its breaking point by keeping pace with the inhuman force of capital? Is it not more unrealistic to think we humans are more akin to capital in its insatiable movement than our fellow lazy animals? In Capital, Marx described the proletariat stripped of both its obligations and means of subsistence as Vogelfrei (“free as a bird”), without recalling how the word used to connote peasant freedom in the Middle Ages. As socialists, we cannot just yearn for the lost golden age, but seek new ways to combine the liberties of the past with the potential of the present to create a future that transcends both. We must strive to be as birds once again—and ensure such freedom for birds too.

1: Thanks to Jacob Bard-Rosenberg for pointing this out to me.

Dining and Cooking