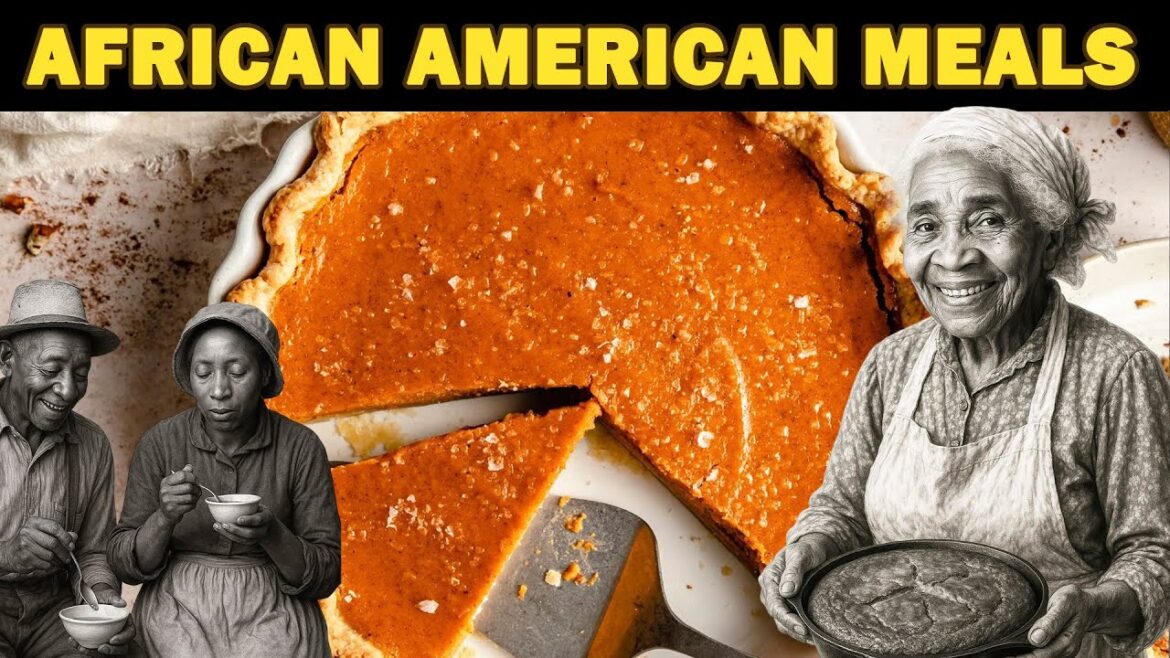

Discover 25 lost African American recipes your grandparents never wrote down — the dishes that shaped Black history, soul food, and Southern cooking. These recipes were born from survival, faith, and love, passed down through generations not by books, but by memory.

From smothered pork chops and collard greens to sweet potato pie and Gullah red rice, each meal tells a story of resilience, family, and flavor. Join us as we explore the roots of African American food traditions, tracing how enslaved cooks and Black families transformed humble ingredients into timeless soul food classics.

🖤 What you’ll find:

The real history behind America’s most iconic soul food dishes.

Forgotten recipes that built Black cuisine.

Stories of strength, heritage, and survival through food.

This isn’t just cooking — it’s memory, legacy, and love served warm.

They told you soul food was just fried chicken and mac and cheese. But they never told you about the Sunday pots where oxtails simmerred for hours and the air smelled like home. These weren’t just meals. They were messages remembered by heart and passed through generations. Stay till the end. One flavor might bring back a memory you didn’t know you missed. One smothered pork chops. They say soul food is all about spice, but sometimes the real flavor came from patience. Back in the South, when the best cuts were never meant for black families, people learned to turn scraps into grace. What was meant to be tough became tender with time, smoke, and faith. The skillet hissed like a memory. Fat melted slow, onions turned golden, and flower dust floated in the air like Sunday light through a window. Every sound was a rhythm. Scrape, stir, sizzle, silence. Grandma would always say, “Don’t rush the gravy. It’s how you taste the week.” If it came out thick, she’d smile. Kids waited in the doorway, not daring to speak until she nodded. That was the sign dinner had arrived. First, the pork chops got a light coat of seasoned flour. Then came the sear. Both sides golden and crisp. After that, a little broth, a handful of onions, and the secret step. Smother is slow till the meat gives in and the gravy tells it story. Smother pork chops weren’t just food. They were proof that even when life burned you, you could still turn it into something tender. A sermon in sauce about survival that tasted like love. Two collard greens with smoked turkey necks. Long before anyone spoke of vitamins or wellness, collard greens were already keeping heart strong and spirit steady. Their roots reach back to West Africa where pots of leafy greens simmer slow with spice and smoke, not as luxury, but as life itself. When those same traditions crossed the ocean into the American South, the greens became sacred, a dish for mourning and for mercy, for family and for faith. In the cabins and kitchens of old, the ritual began before dawn. Turkey necks or ham hawks met the iron pot with a hiss that spoke of patience. Steam rose to the rafters. Onions and fat shared their perfume. And vinegar cut the air like memory too sharp to forget. Each leaf was washed again and again for grit. Whether from soil or sorrow had no place in the pot. Hours passed before the broth turned dark and holy. what the elders called pot liquor, rich enough to feed both hunger and hope. They said that broth could heal a weary soul, cure hunger, heartache, or hard times. Collard greens were never just food. They were a quiet prayer passed down in bowls that kept the people alive long before the world cared to notice. Three, sweet potato pie. No holiday table in a black home ever felt right without the soft orange glow of a sweet potato pie resting on the seal. Steam curling through the evening air. It wasn’t just dessert. It was inheritance. In every family, one person made the pie and everyone knew who it was. Her hands carried the balance of sugar and spice the way a preacher carries scripture, by heart, not by measure. Long before pumpkin pies filled cookbooks and store shelves, sweet potatoes had already claimed their place in southern kitchens. Pumpkin was for those who could afford plenty. But the sweet potato was the people’s gift. Born from African soil and southern struggle. Roasted until caramelized, mass smoothed with brown sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, and a touch of vanilla, it offered warmth that no factory crust could ever hold. The first slice always went to the elder. eating slowly, eyes closed as if listening to the memory baked inside. By morning, the pie was breakfast served cold beside coffee and the sound of quiet laughter. Sweet potato pie wasn’t just sweet. It was the taste of legacy. Humble, steadfast, and written in the language of love. Four, fried catfish. If Sunday had a taste, it would be fried catfish. Crisp on the outside, tender at the heart. Born from the muddy waters that kept people fed when nothing else would. Down by the rivers and creeks, the catfish was more than a catch. It was a blessing. When gardens fell, the wages ran thin. A line cast in dark water could still bring supper home. Some folks said that catfish save whole families more than once, turning hunger into a meal and despair into gratitude. Before the feast, the fish took a short swim in buttermilk, softening the flesh, washing away the river’s grit. Then came the cornmeal, seasoned with black pepper, cayenne, and a little garlic powder. Each fillet coated in a golden promise. When it hit the oil, it sang that familiar song. The sound of survival meeting joy. The catfish was eaten fresh from the pan, passed from hand to hand on paper plates with white bread and hot sauce on the side. It wasn’t fancy, but it was freedom. Proof that even from the muddiest water, something good could rise. It turned survival into celebration and ordinary days into reunion. Five. Hopping John. Before luck charms and lottery tickets, there was Hopin John. A humble bold of black eyed peas, rice and pork, a southern wish for better days. Its roots reached back to West Africa and the Gullet Coast where rice and beans had long symbolized life and abundance. In the south, those same traditions adapted to what was available. Peas grown in garden plots, rice stretched to feed a crowd, pork scraps saved for flavor. On New Year’s Day, it was eaten as a prayer for fortune. Peas for coins, greens for money, cornbread for gold. But even beyond that, one day Hop and John spoke of resilience. How a pot of simple ingredients could feed many and carry hope through hard seasons. Leftovers became Skip and Jenny the next morning, reheated and reborn, just like the families who made it. Six hoe cakes. They called them hoe cakes because they were first cooked on the flat blade of a hoe out in the open fields where fire and iron were all that stood between a person and hunger. The enslaved had almost nothing. No stoves, no pans, no proper spoons, just cornmeal, water, salt, and the will to live. So they mixed what little they had and poured it onto the heated metal, letting the sun and smoke do the rest. Those cakes were survival disguised as breakfast, fast, cheap, and filling. But in the hands of the enslaved, they became something more than food. Each cake was a quiet act of resistance, a way to say, “We’re still here.” As time moved on, ho cakes left the fields and found their place on hearths and cast iron skillets. They hissed and bacon grease or butter, turning golden at the edges, soft in the middle, the taste of endurance turned into comfort. Ho cakes proved that even with no tools, no wealth, and no freedom, people could still create something warm, golden, and proudly their own. A meal born in bondage that rose into freedom one humble cake at a time. Seven. Ham hawks and limema beans. If patience had a flavor, it would taste like this. Smoky, rich, and slow as a Sunday sermon. Ham hawks and limema beans were born from days when hunger sat at every table and nothing could be wasted. The old folks used to say, “If you can’t afford plenty, then cook with time.” And that’s exactly what they did. With scraps of smoked pork, a handful of beans, and a fire that never hurried, they made something worth remembering. In those small southern kitchens, the air was thick with peace. The soft bubbling of beans melting into broth. The scent of smoke and salt. The steady rhythm of a wooden spoon keeping time. It wasn’t fancy food, but it was sacred. The elders would smile and say, “This is how we learn to make plenty out of little.” And they were right. Every bowl was a lesson in patience. Every meal acquired him to resilience. Ham hocks and limema beans remind us what that generation already knew. That dignity doesn’t come from what’s on your plate, but how you make it. And when you’ve got almost nothing, you season it with pride and you let love do the rest. Eight. Gulla red rice. If soul food had an anthem, Gulla red rice would be at steady heartbeat. Along the warm coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, this dish carried more than flavor. It carried a language, a rhythm, a memory. The Gulligi people, descendants of West Africans who kept their traditions alive on the Sea Islands, turned simple rice into a vessel of history. They called it red rice, but it was more than color. It was pride. Cooked in bacon fat or palm oil with onions, bell peppers, and crushed tomatoes, it filled homes with a scent that felt like music. A little time, a touch of cayenne, maybe a scrap of sausage or shrimp if the day had been kind, but even without meat, it sang. Elders said this dish would tell on you. If it came out too dry, you’d been distracted, too wet, and you’d rushed it. Because red rice demanded presence. You had to stir it with care, listen to it simmer, feel when it was ready. In that way, it taught patience, discipline, and pride. Today, chefs write about it, tourists order it, and food writers call it a discovery. But the truth is, it never vanished. It lived quietly in the kitchens of those who remembered. Nine. Chicken and dumplings. When life was busy or a holiday drew near, this was the dish that brought everyone home. A pot of chicken and dumplings bubbling slow, thick with comfort and care. In small southern kitchens, it was cooked for birthdays, Sunday dinners, or any day worth slowing down for. One chicken, sometimes an old hen from the yard, was enough to feed a crowd. boiled with onions, celery, and bay leaf until the broth turned golden and fragrant. When the meat was tender, the dough was rolled thin and cut into strips, then dropped into the pot one by one like tiny blessings sinking into warmth. The kitchen filled with laughter and the hum of voices, the air rich with the promise of a good meal. Families gathered close, passing bowls across crowded tables. Some said it was best the next day when the broth had thickened and the dumplings turned soft as clouds. Chicken and dumplings wasn’t just comfort. It was celebration in a pot. Proof that love could turn a simple bird and a handful of flour into a feast worth remembering. 10. Molasses gingerbread. Back when sugar was a treasure and sweetness was hard-earned, molasses was what kept joy alive in southern kitchens. Thick, dark, and slow as honey in winter. It poured from the tin with a deep smoky scent that filled the room before the oven ever warmed. This was the sweetness that stayed, strong enough to last through lean months, rich enough to turn plain flour into celebration. Women baked molasses gingerbread on holidays and Sundays when there was company coming or a child’s birthday to mark. Some saved the last bit of molasses for Christmas, saying, “Sweet things taste better when you’ve waited for them.” In cast iron pans, flour, eggs, and spice came together by hand. Ginger, cinnamon, and a pinch of clove. Then the batter was poured and baked until the edges cracked and the air turned golden brown with spice and smoke. The smell clung to curtains and clothes, winding through the house like a promise. When it was done, the top gleamed dark and sticky, the inside soft as memory. The first bite burned your tongue just a little, sweet, smoky, and honest. Molass’s gingerbread wasn’t just dessert. It was the taste of waiting, of making do, of turning the smallest sweetness into a moment worth remembering. 11. Oxtail stew. Before the cuts of meat had names the chefs wrote on menus, oxtails were scraps sold cheap but handed down to those who knew how to make something of them. In black kitchens, that something became magic. The tails were brown slow hissing in cast iron till the air turned rich with promise. Onions, carrots, and thyme joined in. Then water, just enough to cover, never more. The stew simmered for hours until the meat slipped from the bone and the broth turned dark and silky. The house smelled like patience, warm, heavy, and alive. Children would wander in, drawn by the scent. And someone always said, “It’s not ready yet.” But when it was, the bowls were filled high, and the room went quiet. Oxtail stew was luxury born from leftovers. A dish that taught the art of waiting and the reward that only slow hands can bring. 12. Chitlins. No dish tested both courage and tradition like chitlins. Cleaned, boiled, and simmered for hours. They filled the house with a smell you never forgot. Sharp, earthy, almost holy in its own way. It was the kind of dish that separated those who only ate soul food from those who understood it. In the old days, chitlins were holiday meal, Christmas, New Year’s time, or homecoming. When families gathered and the elders took charge, they soaked and scrubbed the pork intestines for hours. laughing and telling stories to pass the time. When they finally hit the pot with onions, vinegar, and red pepper, the whole house came alive. By the time they were done, the air was heavy, the windows fogged, and the table full. Folks dressed up for that meal, not because it was fancy, but because it meant history. Chitlins were more than food. They were memory, love, and proof that dignity could rise even from the humblest pot. 13. Candied yams. If comfort had a color, it would shine orange and gold like a pan of candied yams just out of the oven. This dish showed up every holiday, every Sunday dinner, glowing under a layer of melted butter and brown sugar. Children crowded the table early for this one. Spoon and hand before the blessing was even said. The yams were peeled and sliced thick, simmered in sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg, then baked until the syrup bubbled like caramel. The smell was sweet and spiced, the kind that wrapped you around you and made the whole world feel safe. Candy yams didn’t just sweeten the plate, they sweetened the memory. Every bite tasted like home, like hands that fed you even when they were tired. It was the dessert of everyday heroes. Sweet, simple, and full of grace. 14. Red drink. Before soda came in bottles, there was red drink. The color of celebration itself. No Junth wedding or summer picnic was complete without it. Whether made from hibiscus, cherries, or red soda pop, it stood for joy, freedom, and that unshakable sense of being together. Back in the day, folks boil dried habiscus petals. Sorrow they called it. Adding sugar, cloves, and a squeeze of lemon until the ad turned sweet and floral. The first sip hit sharp and tart. The next mellow and cool. On hot days, it tasted like mercy. Children ran around with red stained lips and elders laughed saying, “Now you got the spirit.” Red drink wasn’t just refreshment. It was a toast to survival, to beauty, to every reason people found to keep singing. 15. Grits. In the quiet of morning, before the house woke up, a pot of grits would already be simmering. Steam rose slow from the stove, and the sound, that gentle pop and stir, felt like peace itself. Grits were breakfast, yes, but they were also meditation. Made from ground corn and patience. They were stirred and stirred until smooth, then finished with butter, salt, and sometimes a bit of cheese if the week had gone well. Served with eggs, shrimp, or just a sprinkle of pepper. They warmed the body and the spirit alike. It was the food that greeted the sunrise. Soft, steady, and kind. Every spoonful carried the same message. Start simple, stay grateful. 16. Peach cobbler. No dessert brought people running faster than peach cobbler, fresh from the oven. When peaches were in season, their scent filled the whole house. Sweet, sticky, alive. In summer kitchens, women stood side by side, peeling fruit into tin pans, while laughter and gossip mixed with the sound of spoons and boiling syrup. The crust was simple. Flour, butter, a little sugar, and sometimes just a prayer for enough peaches to go around. Baked until golden and bubbling at the edges, the cobbler came out shining. Its syrup thick as honey and the smell enough to make neighbors stopped by just to say hello. Served warm with a spoonful of cream or ice milk. It wasn’t just dessert. It was a homecoming. Peach cobbler went love was near and that someone cared enough to bake sweetness into an ordinary day. 17. Neckbone soup. There were times when meat was scarce and every bone mattered. Neckbone soup was born from those days. A broth that turned scraps into something tender and whole. The bones simmerred for hours with onions, cabbage, and potatoes until the house filled with a scent as deep as the earth itself. Old folks used to say, “There’s wisdom in a slow pot.” And they were right. The soup taught patience, how to wait, how to stir, how to give things time to become good. When served with cornbread or rice, it warmed more than the body. It was the taste of care. Simple, steady, and honest. The kind of food that said, “We might not have much, but we have enough.” 18. Blackeyed pea fritters. Long before food trucks and frying hoil filled the air at fairs, blackeyed pea fritters were a celebration in their own right. Descended from African Accara, these little golden rounds carried centuries of taste across oceans. In southern kitchens, they sizzled in cast iron, spiced with onion, salt, and just enough heat to make you remember. Served during festivals, church picnics, or after Sunday service, they were crispy on the outside, soft inside. tiny pockets of joy you could hold in your hand. The elder said they brought good luck if eaten on the first day of the year, but most folks didn’t wait that long. Blackeyed pea fritters were proof that joy travels from continent to kitchen, from ancestors to children, one fried bite at a time. 19. Baked mac and cheese. There’s a reason baked mac and cheese sits at the center of every holiday table. It’s not just pasta and cheese. It’s pride. In most families, one person was known for making the mac and everyone else knew better than to compete. Elbow noodles cooked just right. Led with sharp cheddar, butter, milk, and a touch of egg to bind it all together, then baked till the top turned golden and crisp. The smell alone meant something special was happening. A wedding, a reunion, a Sunday feast. When the dish came out, everyone quieted down for the first bite. Baked mac and cheese wasn’t a side. It was a statement. A reminder that tradition can taste like warmth and excellence all at once. 20. Berta milk biscuits. No sound was softer or more sacred than a grandmother’s hands pressing dough on a wooden table. Berta milk biscuits were her love language. Made from flour, lard, and care. Baked before the sun came up. Each biscuit rose golden and flaky. The kitchen filling with a buttery perfume that felt like safety itself. Served with jam, honey, or gravy, they made ordinary mornings feel blessed. Children fought over the first biscuit, and elders smiled quietly, remembering their own youth. These biscuits were never written down in a cookbook. They were learned by watching, by feeling, by heart. The secret ingredient was always the same. Time. 21. Sorghum syrup. Before a store bought sugar filled the shelves, there was sorghum. Dark, slow, and sweet as sunrise over a southern field. Families would gather when the canes were pressed, watching that amber syrup drip like honey from the mill. Children licked their fingers while elders warned, “Patience! Good things take their time. In the kitchen, it sweetened biscuits, cornmeal, and coffee. Poured over hot pancakes or stirred in the warm milk, it carried the taste of earth and sunlight. A sweetness that felt earned, not given. Sorghum served reminded people of balance, that sweetness means more when it comes slow, and that even the smallest harvest could make a season feel abundant. 22. Liver and onions. Not everyone loved it, but those who did swore it made you strong. Fried liver and onions was the meal of working hands. Iron rich, sharp, and grounding. It wasn’t a feast, it was fuel. The kind of food eaten before dawn by men heading to fields by women who had already been awake for hours. The sizzle of liver hitting a hot pan. The smell of caramelized onions. The bitterness mellowed by time. All of it spoke of care disguised as toughness. Parents made it for their children saying, “Eat this. It’ll put strength in your bones.” It wasn’t about taste alone. It was love in its plainest form. Practical, unspoken, but steady as the morning light. 23. Chicken gizzards. Chicken gizzards were for those who knew how to make the most out of little. Fried or stewed, they were chewy, flavorful, and rich. A favorite at fish fries, church gatherings, or Friday nights after payday. The elders laughed, saying, “If you saw somebody eating early, they got the gizzits first.” They were soaked, boiled till tender, then dredged in seasoned flour and fried crisp, served with hot sauce and laughter. The smell alone could pull neighbors from down the block. Gizz were proof that joy didn’t need wealth, just good company, a hot pan, and a reason to celebrate the end of a long week. 24. Cornbread dressing. Every family had one person who made the dressing, and no one dared challenge them. The recipe wasn’t written, just known. Cornbread baked the night before, crumbled and mixed with onions, celery, and sage, soaked in broth until it was just right. Not too wet, not too dry. It showed up at every Thanksgiving and Christmas table. Golden on top, soft in the middle, smelling like gratitude itself. When that first spoonful hit the plate, you could feel the room settle. It wasn’t just food. It was family harmony baked into one dish. Cornbread dressing held history of arguments, laughter, and forgiveness shared around the same table year after year. 25. Blackberry cobbler. Blackberry cobbler was the taste of summer’s farewell. Tautt, juicy, and fleeting. Children picked the berries barefoot, hands and tongues stained purple by the time they brought them home. The berries went into sugar and dough, baked till the kitchen smelled like sunlight caught in syrup. By evening, it was spooned warm into bowls, the crust breaking into sweet crumbles under melting cream. It was gone by morning like the season itself. Too short, too beautiful. Blackberry cobbler reminded everyone that sweetness doesn’t last forever and that’s what makes it precious. It was memories served warm. The taste of endings made gentle by love.

1 Comment

This was such a great video! Thanks for sharing these treasured culinary delights! I am from Manning, SC 💙🤍