Do you use cookbooks? I have to say that I don’t; which may explain why I am such a bad cook. My problem is that I lack the patience to follow a recipe. And all my cooking is pretty last minute, which means that by the time I decide to cook and start looking at a recipe I discover that I don’t have half the ingredients, decide to improvise and end up making an entirely different dish.

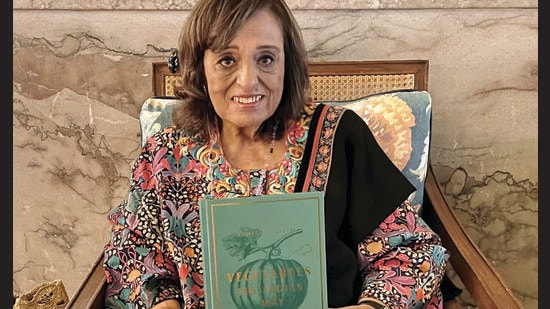

Restaurateur Camellia Panjabi’s cookbook, Vegetables The Indian Way, takes the mystery out of cooking.

Restaurateur Camellia Panjabi’s cookbook, Vegetables The Indian Way, takes the mystery out of cooking.

For years, I have consoled myself with that old cliché about the difference between the French and the British. A Brit, it is said, finds a recipe, makes a list of all the ingredients required, and goes out and buys them before starting work in the kitchen. The French, on the other hand, go shopping, find fresh and interesting ingredients and then come back home and work out how to use them.

This sounds good in theory, but is not actually true. French cooking can be complex and involves exact quantities of each ingredient so, unless you are Alain Ducasse or Anne-Sophie Pic and can invent perfect recipes on the spot, the recipe is crucial to the process.

While some hotel chains keep their recipes secret, the Taj has published books to share theirs.

While some hotel chains keep their recipes secret, the Taj has published books to share theirs.

You only realise how important recipes are when you see professional chefs fight over them. They hide their recipes (even from each other), and a line cook who has worked in a Michelin three-star restaurant will always get another job in a fancy restaurant because he will know the secrets of the chef at the three-star restaurant and will be able to reveal the recipe.

That’s as true of Indian food. For instance ITC, unlike most hotel chains, will not let its chefs publish the recipes of its most iconic dishes, because it regards them as proprietary information.

The Taj, in contrast, has always shared its secrets and its recipes and has even published cookbooks on the grounds that culinary knowledge is meant to be shared. Modern chefs in India have followed the Taj’s lead; the Indian Accent cookbook contains recipes of the restaurant’s most famous dishes.

Modern chefs have followed the Taj’s lead. The Indian Accent published their famous recipes too.

Modern chefs have followed the Taj’s lead. The Indian Accent published their famous recipes too.

The Taj’s approach to recipes always reminds me of Camellia Panjabi, who spent decades with the group, tracking down every recipe worth knowing and explored many Indian cuisines that were unknown outside of private homes.

When the Taj Bengal opened in Kolkata in 1989 one of its restaurants was called Sonargaon and was expected to be the first upmarket Bengali restaurant in the world. I waited eagerly for it to open (I lived in Kolkata at the time and was frustrated by the lack of good Bengali restaurants.) But when Sonargaon did open, its specialties included kakori kababs and Awadhi biryani. Only the servers were Bengalis.

I investigated and discovered that Ajit Kerkar, Camellia’s legendary boss at the Taj, had been approached by a manager and two chefs from ITC. The tree of them were willing to defect, they said, for the right price and would bring their recipes with them. Kerkar grabbed the opportunity, and because Sonargaon had yet to open, installed them there, ditched the Bengali concept and launched an ITC type menu.

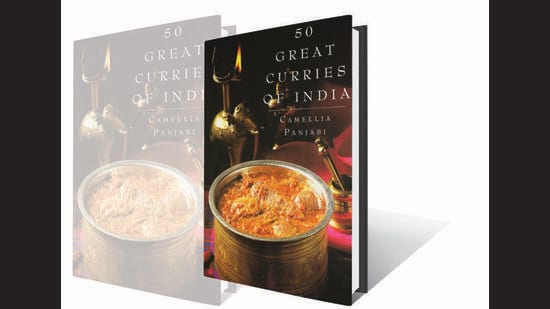

Camellia’s 50 Great Curries of India was so simply and clearly written, it was an instant bestseller.

Camellia’s 50 Great Curries of India was so simply and clearly written, it was an instant bestseller.

It worked well. The food was very good and the restaurant was packed.

Then, a few months later, I went for lunch and found that the food was not very good. The manager explained sadly that ITC had lured the chefs back. In the finest tradition of their former employer, they had, during their time at Sonargaon, refused to divulge any of their recipes or train any of the Taj chefs. “We have stopped serving the kakori kabab because our chefs can’t work out how these guys used to be able to wrap the keema mixture on the skewer. When our chaps do it, the keema keeps dropping off the skewer,” I was told by the distraught manager.

This was three decades ago. Since then, ITC has opened many other hotels and has relaxed its attitudes to recipe secrecy, realising that even though hundreds of chefs have left the group, not one of them has been able to create any restaurant in the league of Bukhara or Dum Pukht.

Though she is not obsessively secretive, Camellia has never forgotten how crucial recipes are. When she opened the new Chutney Mary in London she remembered the best Do Piyaza she had eaten years ago, tracked down the cook who had made it and bought the recipe from him. (If I remember correctly the secret had to do with the proportion of fried onions or ‘brown’ onions to fresh onions).

Few chefs create recipes that home cooks can follow. The exception is Heston Blumenthal.

Few chefs create recipes that home cooks can follow. The exception is Heston Blumenthal.

Camellia is not a chef; she is a restaurateur. The distinction is important because very few chefs create recipes that home cooks can follow; they are just showing off to other chefs. The exception is Heston Blumenthal, who has written the very technical The Fat Duck Cookbook as a way of recording his flagship restaurant’s innovations but has also published the invaluable Is This A Cookbook? for home cooks.

Camellia takes the same approach as Heston. The complex recipes are for her restaurants. Her cookbooks contain recipes that are so simple and so dependent on everyday ingredients that even I can use them.

Two decades ago, Camellia published 50 Great Curries of India, a cookbook that was so simply and clearly written that it went on to become one of the bestselling Indian cookbooks in the history of publishing. I wondered if she could ever top that. And now she has, with Vegetables The Indian Way, one of the few cookbooks where the cover blurb accurately sums up the contents: “A definitive collection of recipes from the simple to the special.”

Like her curry book, it takes the mystery out of cooking, and though it is directed at the global reader, any Indian home cook will benefit from her wisdom.

Because Camellia is not a chef, she is frank about the origins of her recipes. The Nizami Biryani recipe, for instance, comes from ‘the legendary Mumtaz Khan of Hyderabad, who was from an aristocratic family and was a famous wedding caterer’.

Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck Cookbook, on the other hand, is more technical.

Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck Cookbook, on the other hand, is more technical.

Her dal recipe is so straightforward that even an American making Indian food for the first time will be able to make a perfect dal. And she always distinguishes between home recipes and restaurant food. Her ‘Buttery Textured Mung Dal’ recipe comes from the dal we eat at home with a delicious tadka. But there is also a recipe for restaurant style Dal Makhni, which requires 75 grams of cream.

And there is a surprising quantity of information. She makes it clear that the real difference between a green and a red chilli is how long the fruit spends on the branch before it is picked. And she reassures nervous cooks by pointing out that large green peppers (Simla mirch) do not contain capsaicin, the substance that makes smaller chilis hot.

One reason why 50 Great Curries did so well was because it contained the word Curry in the title at a time when the world had just begun to take notice of Indian food. Vegetables The Indian Way may have a similar advantage. It comes at a time when the West is just rediscovering vegetables, and when people are tiring of Indian food that is greasy and heavy and want something that is lighter and more delicately flavoured.

For Indians, there is an additional advantage: It uses ingredients we already have in kitchens and the recipes are so varied that no matter what sabzis your vegetable vendor has on the day, Camellia will have a suitable recipe.

And finally: It’s good to see a cookbook that recognises the importance of restaurant dishes but is focused on the best Indian dishes; the ones we eat at home every day.

From HT Brunch, November 1, 2025

Follow us on www.instagram.com/htbrunch

Dining and Cooking