LONDON — It is a simple equation, especially for a mathematician. Loved ones, plus food, equals good times.

Iacopo Iacopini, an associate professor in network science at Northeastern University, grew up in Marche, a region in the east of Italy, a country where food is the “driver of any social event,” he says.

“The memories I have from when I was very young,” he continues, “are related to people and events, and very often these socializing moments happen around the dinner table or lunch table, so these things are very much connected.”

He distinctly remembers helping his nonna to prepare gnocchi — small, chewy dumplings often made from potato — during family gatherings.

“When I was very little, she would let me cut her gnocchi and, if two of them remained on the table, then one would end up in my mouth,” Iacopini recalls with a laugh, thinking of the memory of his grandmother.

Iacopo Iacopini is an associate professor at the Network Science Institute in London. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Iacopo Iacopini is an associate professor at the Network Science Institute in London. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

With that Italian love of meal times instilled in him, he had the idea of researching how cuisines work as a network when browsing through the extensive Giallo Zafferano food recipe website, looking for inspiration for something to cook.

The member of the Network Science Institute started to mull over a quote from “Ratatouille”, a Disney film about Remy, a rat that aspires to be a chef. The rodent says: “Imagine every great taste in the world being combined into infinite combinations. Tastes that no one has tried yet!”

Iacopini says this line sums up his curiosity in wanting to understand, with so many ingredients at our fingertips, why it is that cuisines have evolved to congregate around a distinct set of flavors that “favor some combinations over others.”

That fascination resulted in his most recent paper, “The networks of ingredient combinations as culinary fingerprints of world cuisines,” published by the npj Science of Food.

The London-based researcher and his colleagues — Claudio Caprioli from the University of Catania in Italy, Saumitra Kulkarni of Savitribai Phule Pune University in India, Federico Battiston from the Central European University in Austria, Andrea Santoro from the CENTAI Institute in Turin and Vito Latora from the Complexity Science Hub, also in Austria — investigated how different ingredients are combined in popular dishes in an effort to uncover the principles behind food preferences.

The analysis found that, when recipes were broken down and studied, “distinctive patterns” emerged that serve as “culinary fingerprints.”

Indian food, for example, had the central component of spices in its recipes, Iacopini explains, whereas food in so-called “new world” countries such as the United States, Canada and Australia are “more homogenized.” “This could be due to the strong immigration cultural blending that has been going on in those places,” he adds.

The dish featuring the most ingredients was a top restaurant favorite from Indian cuisine — vegetable korma, made up of 31 items, including star anise, sunflower and bell peppers. The second most ingredient-heavy recipe in the data set was found in American cuisine — a Turkey, sweet potato shepherd’s pie and cran-apple sauce sundaes.

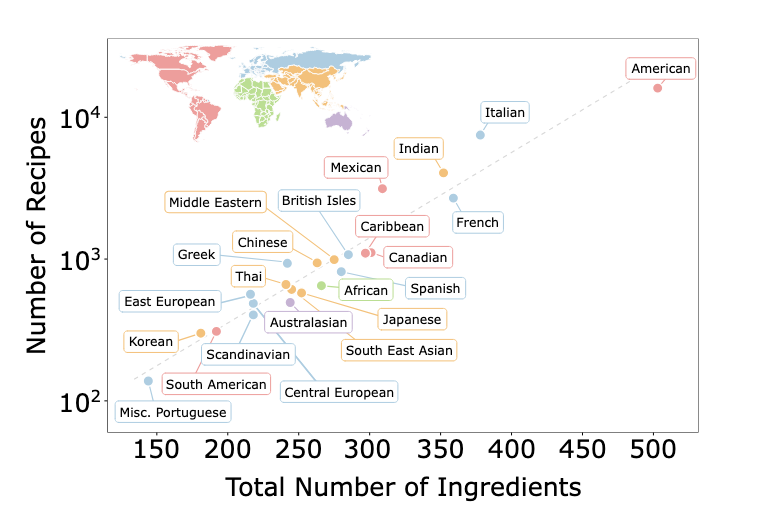

The culinary research delved into which cuisines used the most ingredients in its recipes. Courtesy of Iacopo Iacopini

The culinary research delved into which cuisines used the most ingredients in its recipes. Courtesy of Iacopo Iacopini

The work involved studying a data set of recipes covering 23 cuisines around the world — ranging from Thai to Eastern European — and containing details of 45,661 recipes made up of 604 ingredients. The authors simplified the ingredient set to 20 network groupings. It meant that all cheeses, eggs and milk came under the single category of “dairy.” Other categories chosen were fungus, herbs and meat.

They used that basis to work out what ingredients were most popular in each cuisine. The findings backed up geographic, social and historical reasons for certain cuisines being the way they are, Iacopini says.

For example, India stood out as the cuisine that uses meat the least, reflecting cultural restrictions on meat consumption, especially among its vast Hindu population. Similarly, the impact of geography on ingredient usage was borne out by Scandinavian cuisine, which shows significantly lower usage of ingredients from the vegetables, herbs, and plants categories compared to most others.

“The harsh climate of Scandinavian countries creates unfavorable conditions for the cultivation of most vegetables, resulting in a distinct culinary approach that relies on other ingredients,” the authors state.

What Iacopini found remarkable was that, even when entering a combination of the scaled-down 20 ingredient categories, a simple off-the-shelf machine learning technique, in this case a Support Vector Machine, was able to accurately calculate what cuisine it was from with 95% accuracy.

Enter the categories cereals, meat and dairy, for example, and the machine was highly likely to calculate that this simple description of a carbonara recipe, traditionally made with pasta, eggs, pecorino and guanciale, emerged from Italian cuisine.

“It shows that a lot of information about the cultural aspects is simply already in the way that these ingredient types are combined, so you don’t need to go into a super granular level of detail,” Iacopini says.

It can be the simplest equations that invite the most cause for fascination and future investigation, he says.

“There is a lot of information here in the way that these pairings work without going into the compound level or the chemical level,” he continues. “I think this is interesting and it opens up research directions in network science. We would like to study the evolution of these cuisines through the ages.”

Dining and Cooking