This article was produced by National Geographic Traveller (UK).

The Amish are fond of a sweet treat, Fannie Yoder tells me as we wander the aisles of her delicatessen in Tennessee’s Amish Country. She’s not kidding. Around us, shelves groan beneath glossy slabs of fudge. There are towers of cinnamon rolls, swirled high with thick peaks of icing. Stacks of sugared doughnuts and fried pies stretch to the far wall, oozing jam. “It has to be homemade, using good ingredients,” the 73-year-old is quick to clarify, a crisp white bonnet framing her face. “I once made a cake using a store-bought mix. My six children knew instantly it wasn’t my baking,” she reveals, her eyes behind pebble-shaped, wire-framed glasses crinkling into a knowing smile.

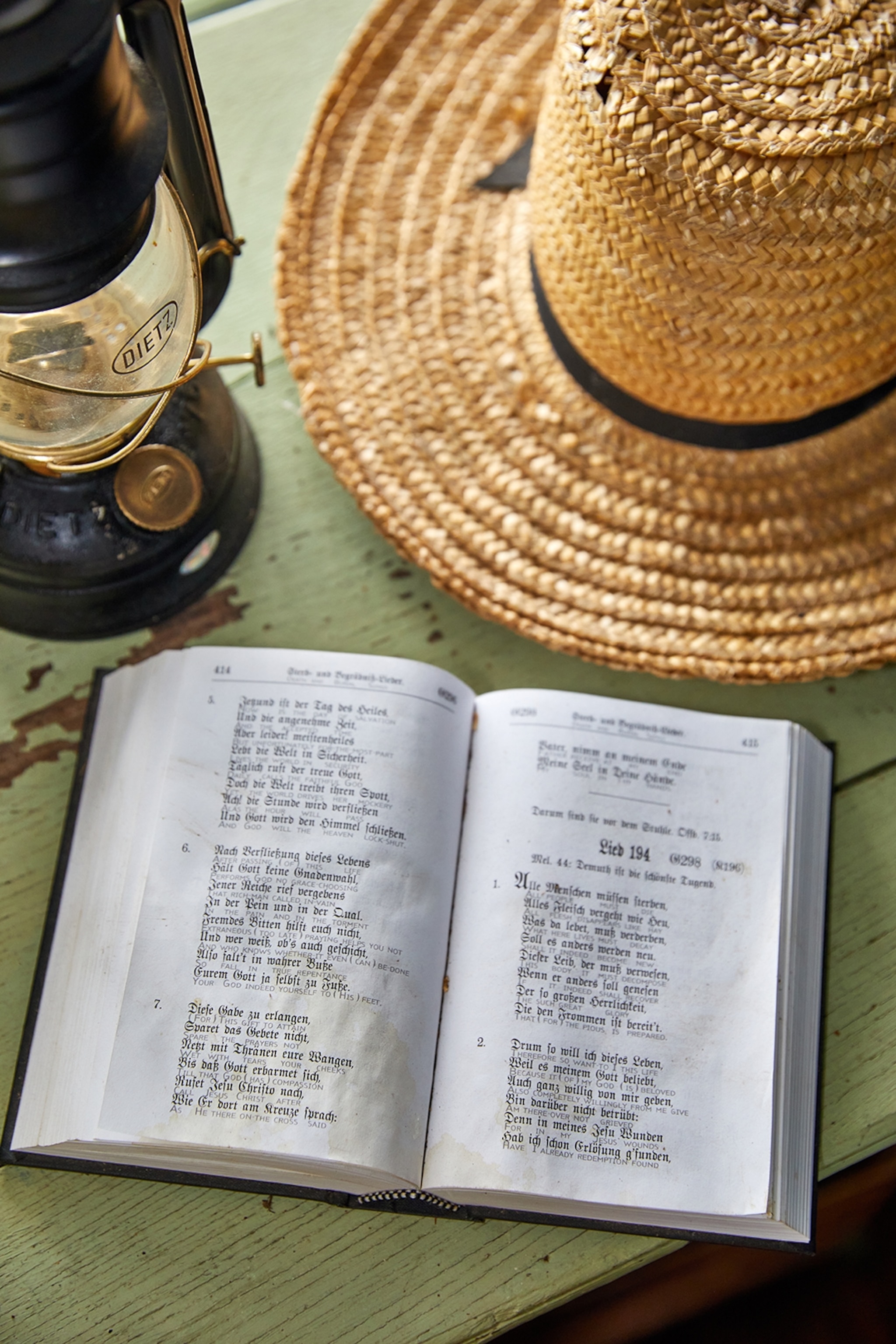

I’ve come to Lawrence County in the south-central region of Tennessee, 80 miles south of Nashville, to visit the Amish community of Ethridge and its surroundings. Home to around 2,200 people, it’s the largest Amish settlement in the US South. The families here mostly belong to the Swartzentruber affiliation, one of the most conservative Amish groups in the country. Since settling in this stretch of rolling farmland in 1944, they’ve lived without electricity, indoor plumbing, cars or technology — instead, they cook over open fires and travel by horse and buggy.

The Amish in Tennessee are Old Order Anabaptist Christians, the most conservative in America, living entirely without cars and other modern technology.

Photograph by Shell Royster (Top) (Left) and Photograph by Shell Royster (Bottom) (Right)

While this settlement of Old Order Anabaptist Christians remains remarkably separate to the wider world, the door has been nudged open somewhat in recent years. Wagons carrying tourists clip-clop along leafy country lanes, pausing at Amish workshops — wooden outhouses that recall my grandpa’s tool shed, right down to the earthy smell — with a bench in the centre piled high with goods for sale. Maps guide visitors to individual homesteads where a bounty of fresh crops, homemade baked goods and handcrafted leather and woodwork await shoppers. Nearby, an Amish farmer’s auction draws curious onlookers eager to discover more about this cloistered community.

Yoder’s Homestead Market, opened by Fannie and her husband Noah in 2005 in the enclave of Summertown, is another place where visitors can connect with Amish culture. The Yoders are Amish, though more progressive than their neighbours just 10 miles down the road in Ethridge. That distinction means they farm with tractors, use a phone for business calls and operate their self-built cafe, deli and store using electricity.

As the heady scent of baking fills the air, Fannie smooths a starched cotton apron over her ankle-length turquoise smock dress. Just beyond the deli counter, in a tiny kitchen, sourdough loaves rise languidly in three warm ovens, ready for the lunchtime rush. Lattice-topped strawberry, rhubarb and blueberry pies cool on the counter, soon to be set out on red-and-white gingham tablecloths, as pretty as a country postcard.

Alongside baking, Fannie is well-versed in the fine art of pickling, fermenting and canning — time-honoured methods of preservation passed down through generations. These skills allow the Amish to live largely independent of supermarkets, processed foods or refrigeration. “I grow cucumbers in the garden and slice them thin,” Fannie says. “Then I pour over a brine of vinegar, sugar, salt, dill and garlic. I leave them to marinate for two weeks before opening the jar, so the flavour seeps into everything. I can easily do 30 jars at a time.” Hers is the industrious mindset of someone who’s spent a lifetime working from sunrise to sunset.

Fannie Yoder, co-founder of Yoder’s Homestead Market in Summertown, is among the more progressive Amish in the area, using electricity and phones for business calls.

Photograph by Shell Royster

Typical barbecues in Summertown always include pickles, which are a traditional method of preservation in the Amish community.

Photograph by Shell Royster

On Fannie’s recommendation, I take a bite of chess pie, a sweet staple whose name is believed to be a corruption of either ‘cheese’ or ‘chest’ — the latter noting where it was stored, without the need for refrigeration. Its texture is somewhere between set custard and sponge cake, cradled in a delicate, buttery crust. It’s creamy, rich and teeth-tinglingly sweet, made from just a handful of pantry staples: sugar, eggs, flour, butter, vanilla and a splash of buttermilk. “Those were the ingredients early pioneers had on hand,” Fannie explains.

“Chess pie is definitely a Southern thing,” she adds. “But most Amish recipes go further back — to Europe, mostly Germany.” In the 1700s, Amish families left Germany, Switzerland and France to escape religious persecution, settling in North America in search of freedom. While Amish culture evolved on American soil, their culinary roots remain unmistakably European, something you can see in every aisle of Yoder’s Homestead Market. “We like our food to have flavour,” Fannie says. “And like in Germany, we cook up a lot of sweets, pies and cakes.” Before I leave, she hands me a bag of cinnamon rolls, warm from the oven and deliciously sticky. It’s the kind of send-off you’d expect from a treasured grandmother.

On the wagon

There’s no mistaking I’ve arrived in the beating heart of Amish Country on the approach to Ethridge. A yellow horse-and-buggy caution sign glints at the roadside where a dedicated lane along the highway allows Amish buggies to trot safely. I’m here to meet Owen Lewis, who, along with his wife Jodi, founded Amish Country Wagon Tours in late 2024. Though they’re not Amish — they’re ‘English’, as the Amish refer to outsiders — the couple grew up alongside the community and now runs horse-drawn tours around Amish country.

As the wagon wheels begin to roll, Owen swivels around in the driver’s seat. “This community started out with just five families, who came from Mississippi and Ohio in search of fertile ground for farming,” he says as we pass a pair of clapboard farmhouses where a multi-generation family reside, the grandparents living in a house at the back called the ‘dawdy haus’. At the front, a washing line flutters gently in the breeze, strung with plain blue work shirts, black trousers and white aprons, each pegged in neat, colour-coded blocks.

Trucks are of little use to the Amish settlement in Ethridge — buggies are a far more common sight.

Photograph by Shell Royster

We pull up beside a rust-red barn, where a gaggle of young children are drawing water from a well — shoeless, as is the Amish way during the warmer months. “They only speak Pennsylvania Dutch,” Owen tells me, referring to the German-rooted dialect spoken at home. He adds that Amish children don’t learn English until they begin school, and that formal education, which occurs in one-room schoolhouses, typically ends at age 14. “You have to remember,” Owen reflects, “that unlike us, the Amish aren’t trying to climb the corporate ladder. They want to provide for their families and live a simple life.”

From the porch of our next Amish house, I buy a sandwich bag of peanut brittle, a honeycomb-like bar packed with roasted nuts. It isn’t your stingy supermarket version, but a chunk as thick as a deck of cards. It sticks to my teeth for the duration of the wagon ride in a most satisfying way, the taste lingering on like the closing note of a favourite song.

Our tour makes one final turn down a sun-dappled lane to Jacob Gingerich’s farm, where a modest wooden shed doubles as a workshop and storefront. Here, Jacob sells his wooden funeral caskets, each one carefully handcrafted. He’s just returned from the fields, reins still in hand, his horse-drawn cart piled high with cucumbers, onions and beets.

“I’m growing so many cucumbers, they’re coming out of my ears,” he says laughing. Children too, it seems — Jacob is father to eight, two of whom ride high on the cart, wide-brimmed straw hats tilted just like their father’s. “Try one of these,” Jacob says, offering me a pickling cucumber plucked from the vine just minutes before. I bite through the bumpy skin to taste the crisp, clean snap of summer, wishing I also had a wedge of crusty bread and an afternoon to while away.

Life in the slow lane

Wagon rides aren’t the only way to explore Amish Country. The local tourism board recently introduced a self-guided driving map, which is free to download or pick up at most stores and connects the dots between more than 170 Amish-owned farms and workshops selling their wares. I often spot it displayed on foldout wooden tables at the front of homes.

Hand-painted signs at the roadside also advertise what’s available, making the route surprisingly easy to follow. Puppies, jams and jellies, funeral caskets, baby swing sets, rolling pins, pickled okra, bunnies, leather chaps — the signboards read like a delightfully unhinged shopping list. I spend a few hours cruising the route, scooping up bars of scented goat’s milk soap and a bentwood woven handbag with the maker’s name and address scrawled on the bottom.

Amish farmers’ auctions are lively events, where local producers sell off their most prized harvests to the highest bidder.

Photograph by Shell Royster (Top) (Left) and Photograph by Shell Royster (Bottom) (Right)

As my time in Amish country draws to a close, I make one last stop at the Plowboy Produce Auction, an open-air market held three times a week from April to October. The gravel crunches beneath my tyres as I pull into a lot lined with snorting horses hitched to black buggies, parked alongside pick-up trucks overflowing with cardboard boxes of fruits and vegetables. From within a knot of Amish farmers, long beards brushing their braces, the auctioneer’s sing-song patter fills into the air.

The auction was the vision of Susan Ayers-Kelley, an ‘English’ who once came here simply to buy what she calls the gold standard in produce. With the Ethridge Amish avoiding modern technology, scaling up their businesses was a challenge. In 2006, Susan stepped in, creating a bridge between the farmers and the chefs and wholesalers who now travel from across 15 states to snap up their harvest.

“When I arrived, I made a deal with the Amish: ‘If y’all can grow it, I can sell it,’” the owner recalls in a thick Southern accent. And sell it she did. Today, Plowboy Produce Auction shifts around $2 million (just under £1.5m) in goods each growing season, with much of that Amish-grown produce landing on the white-clothed tables of the South’s most celebrated restaurants.

Against a backdrop of punnets filled with peaches the size of fists, I meet the second Jacob Gingerich of the day. Originally a dairy farmer from Ohio, he’s grown his farm into a powerhouse of productivity since moving to Ethridge. “I’ve sold 50 boxes of tomatoes and cucumbers today,” he says with a shrug, adding this is pretty standard. When he needs to ramp things up, he works the fields with five horses lined up, side by side.

“Around 99% of the food sold here is grown by the Amish within nine miles of where we’re standing,” Susan adds, pausing in the midst of a conversation she’s having with a farmer proudly boasting about his 17 children, before noting a neighbour has 18. “Each sale, I’m amazed by where people are visiting from: Hawaii, Europe, New Zealand. We sometimes get whole busloads of tourists,” she marvels. An upswing in visitors to Nashville has created a ripple effect. “It’s so close, folks want to drive out and see Amish Country for themselves.”

As I make my own way back toward Music City, fields of golden oats gradually give way to skyscrapers. Neon signs flicker outside honky-tonks, music blasts from dive bars. A bridal party cheers as they pedal past on a pub bike, drinks in hand, pink cowgirl hats bobbing. It’s hard to believe that just 90 minutes away, life unfolds as if someone hit the pause button in the early 1900s. In Tennessee’s Amish Country, its farming community has done what many of us only dream of: stilled the relentless hands of time.

How to do itAmerica As You Like It offers a seven-night fly-drive to Tennessee from £1,355 per person, including return British Airways flights to Nashville, seven days’ car hire, four nights at the Millennium Maxwell House in Nashville and three nights at the Best Western Plus in Lawrenceburg, on a B&B basis.

Getting there & around

British Airways flies direct from Heathrow to Nashville, with one-stop flights from many other UK airports on Aer Lingus.

Average flight time: 8h30m.

Public transport between Nashville and Ethridge is non-existent, so hire a car from Nashville International Airport, which is home to the usual rental companies.

When to go

The growing season, from April to October, is the ideal time to visit Tennessee’s Amish Country. Farmers are out working the fields, stalls overflow with fresh produce and the Plowboy Produce Auction is in full swing. July and August bring the warmest weather, with highs around 31C, bluebird skies and sun-drenched days that stretch late into evening.

Where to stay

Best Western Plus, Lawrenceburg. Doubles from $130 (£96), B&B.

More info:

experiencetn.com

Rough Guide to USA: The South. £9.99

This story was created with the support of Tennessee Tourism.

Published in the November 2025 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK).

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).

Dining and Cooking