Last week, Drinks Trade travelled to the Riverland with Hill Smith Family Estates and Oxford Landing Wines for a three-day immersive.

The trip explored a broad range of subjects, including insights into the region responsible for 27.9 per cent of all Australian wine, the winery’s unique direct action sustainability program, and the challenges of making quality wine at the immense scale at which Oxford Landing operates.

This scale is hard to comprehend. According to Winemaker Matt Zadow, who led the tour of the Nuriootpa winery, Oxford Landing is generally crushing between 30,000 and 35,000 tonnes every year, and up to 900 tonnes a day during peak season.

This equates to more than 2 per cent of Australia’s overall winegrape crush in vintage 2025. If the facility were to run at its full capacity of 50,000 tonnes, this would be above 3 per cent.

Despite the scale, Senior White Winemaker Pat Connors describes Oxford Landing as “a beautiful, sustainable wine.

“Riverland, Sunraysia, Griffith have probably got a bad rep for bulk wine on the bulk scene, but we’re growing labelled bottled wine: we’re trying to be a premium vineyard, premium winery in the commercial sort of industry,” he adds.

Dr Greg Nattrass and Matt Zadow (left); the weighbridge for incoming trucks (top centre); decision dams (bottom centre); Zadow explaining the crushers (right)

Starting the tour on the day at the production facility was Hill Smith Family Estates’ R&D Manager and Microbiologist Dr Greg Nattrass.

“When we make wine, it’s pretty much six to 12 weeks of the year when we’ve got ripe grapes, and the role of the microbiologist is to ensure that the good guys, the yeast and bacteria that convert sugar to alcohol, do their thing,” he explained during the tour.

“Once we’ve got what we call finished wine in tank, we then monitor that and make sure that the bad guys, which are what we call spoilage organisms, don’t destroy all the good work that we’ve done.”

Perhaps one of the most impressive facts about Oxford Landing’s winemaking process is that it primarily uses native yeasts for fermentation. This can only be achieved thanks to the care employed in the vineyard, which spans about 13,000 hectares and 12 to 15 varieties and is Sustainable Winegrowing Australia certified.

Pat Connors in the Oxford Landing Vineyard (left, top centre), Glynn Muster in the vineyard and nursery (bottom centre, right)

Speaking with Drinks Trade, Oxford Landing’s Senior Winemaker Pat Connors and Vineyard Manager Glynn Muster both note the increasing importance of technology in improving both the quality potential and efficiency of commercial vineyard operations.

“We’re getting smarter with technology,” Pat Connors said. “On the tour Glynn was talking about moisture probes and feeding the vines the correct amount of water, so you’re not wasting water. Just five years ago, we talked about the overhead sprinklers: it’s going to be hot for the next four days, turn sprinklers on, and half that water was just being wasted. This is all electronically monitored. Everything’s getting the exact right dose.”

Australia’s warm inland wine regions exist because of irrigation

Pat Connors expects the technology available in the vineyard to continue to develop over the next few years, with wider adoption to follow suit.

“Currently, because we’re in this slight surplus phase of wine, a lot of wineries are a little reluctant to uptake some of that technology because it doesn’t come cheap, but I think once we catch up on some of that surplus, [once] wine and the industry gets back to a nice, happy medium, you’ll see a lot more of that.”

One example Connors raised is the use of drones to map vineyards and assess areas that aren’t getting the correct amount of water supply based on canopy vigour.

Similarly, in the winery, Matt Zadow outlined a number of initiatives and technologies all designed to bring water usage down to one litre of water for every litre of wine.

“We’re at 1.1 at the moment,” said Zadow. “We’re close, but sometimes it’s seasonal, depending on the conditions and things like that.”

One of these technologies is the use of decision dams, (see first image), which provide autonomy for how waste water and wine losses are allowed to flow around the property.

Matt Zadow explains, “if we’re just washing a tank, it’ll go into that treatment facility and get treated, [or] if we have a hose break or a seal on a tank go and a large volume of wine go down there, we don’t want to have that go into the freshwater dams, so it’s automatically sent straight to the treatment plant, and then we can check.”

Another simple water-saving technology is a large moat all the way around the winery that collects all run-off and rain water from the breadth of the property.

Matt Zadow explaining the CO2 capture systems (left, centre); a few of the many solar panel clusters at the Oxford Landing winery

Beyond water, Oxford Landing is also looking to improve its sustainability across all touch points, including new modified caps for fermentation tanks capable of receiving and storing CO2.

Matt Zadow says the initial results from the trial have been very promising.

“The only issue is you generate a large amount of CO2 in a short amount of time, so storing that to use over a 12-month period is not economical. But we can see the benefits to use that during winter.”

This includes using recycled CO2 to fill the headspace in partially filled tanks to prevent oxidation: “If the wine tank isn’t quite full, we just dribble CO2 into it to keep that oxygen layer away from the top of the surface of the wine. But we can use CO2 generated during fermenting for other purposes in the wine – it’s a really, really important part, and will help our sustainability eventually.”

Another key sustainable practice employed at the winery is in regards to the lack of waste. Prior to crushing the stalks and the leaves are removed and put into a pile that either goes to compost or to local farmers for cattle feed.

Similarly, once the white grapes are pressed the skins and seeds are taken by leading alcohol supplier Tarac to be fermented and turned into alcohol that is then re-sold back to wineries to reuse.

Finally, for the red wines, the skins and seeds are pressed out and Tarac will extract any remaining alcohol along with the acid, tannins, and colour extracts.

“No waste not being reutilised,” says Zadow. “So we recycle everything that’s here generated as waste and then they process it and sell it back to us for different additives for different things.”

However, broadly speaking, Pat Connors expects most of the opportunity for new technologies will apply to the vineyards.

“There’s always been a lot of support from specialist departments like the AWRI and what have you, but they had concentrated a lot on the winery processing,” he said.

“They put big emphasis on making wineries, but there was probably not a lot of focus on vineyards. I think now we’re starting to see the turnaround point where now the focus is on looking after the vineyard.”

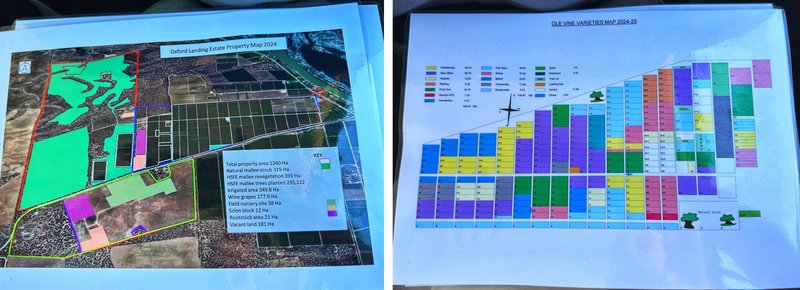

The Oxford Landing Property by use-case (bright green is mallee scrub as part of its one square metre planted for every six-pack sold initiative)(left); The vineyard by variety (right)

Another key takeaway from the trip is the importance that small decisions can have when scaled up to 35,000 tonnes a year. This includes the winery’s transition to the current lightest weight glass available, which Matt Zadow says “is saving us 250 tonnes of carbon each year.”

Beyond the emissions saved from the reduced weight, Zadow says “when you make the glass thinner, it takes up less space, and you can put more bottles into each shipping container.”

In a similar vein, regulatory changes such as the UK’s newly-introduced tiered alcohol tax could have also had a significant impact on Oxford Landing, one of Australia’s leading wine brands in the UK, once applied at scale had it not adjusted its red wines to meet the 10.5% abv threshold.

“If you go from 10.5 to 11.5, there’s 22p tax per bottle of wine. Some of our shiraz and cabernet used to be 13.5%, so that’s an extra 66p per bottle (which would be $1.20, $1.30 Australian) and consumer perception is that you’ve got to keep it at the same price point, you can’t increase it, so producers had to absorb some of that and distributors had to absorb some of that.

Matt Zadow continues: “Now, alcohol is an important part of the wine because it actually gives the perception of fullness and sweetness, so you take the alcohol out and all of a sudden you’ve got a high acidity layer there, so you need to do things in the winemaking process to make it look like a wine should taste. We’ve been doing lots of things … that just builds texture and weight.”

Out of Oxford Landing’s UK exports, sauvignon blanc is by far the most significant, and is the best-selling Australian sauvignon blanc import.

The new Oxford Landing bottles and labels

The visit also shone a light on the importance of community, and the role that community has played in influencing Oxford Landing’s sustainbility initiatives.

As Pat Connors puts it, “Glynn and I, and probably most people that work in the industry, are quite passionate about the wine industry, and so if we don’t look after it, what does the future hold? I think to look after the wine industry means doing the right thing by our environment and by our consumers. It is the environment, so the environmental side; the people, so the social side; the community – all those things. We live in country communities, if we don’t [look after it], we don’t exist.”

More insights from the trip will be published digitally and in our upcoming print publications over the coming months

//

Oxford Landing is saving the planet one bottle at a time, and consumers are listening

Dining and Cooking