Excavations led by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in ancient Roman Cillium, a border area of Tunisia near present-day Algeria, are uncovering imposing structures linked to olive oil production, among which stands out, due to its colossal dimensions, a torcularium identified as the second-largest Roman frantoio in the entire Empire. A frantoio is a Roman industrial-scale presshouse or oil mill, equipped with beam presses (torcularia), dedicated to the large-volume production of olive oil for commercial distribution.

The excavation campaign, which this year counts on the active participation of Professor Luigi Sperti, Deputy Director of the Department of Humanities and Director of CESAV (Center for Studies of Venetian Archaeology) at Ca’ Foscari, focuses on two ancient olive-growing farms nestled in the heart of the Jebel Semmama massif. This territory, characterized by its high-steppe landscape and a continental climate with strong temperature fluctuations and modest precipitation stored in wells, offered ideal soil and climatic conditions for olive cultivation, a strategic resource that propelled the economy of Roman Africa and turned present-day Tunisia into the main oil supplier for the city of Rome.

This border region of Africa Proconsularis, once inhabited by the musulamii—populations of Numidian origin—formed a complex node of encounter and exchange between Roman imperial power, veteran colonists, and local Indigenous communities, a cultural melting pot whose socioeconomic dynamics are only now beginning to be unraveled.

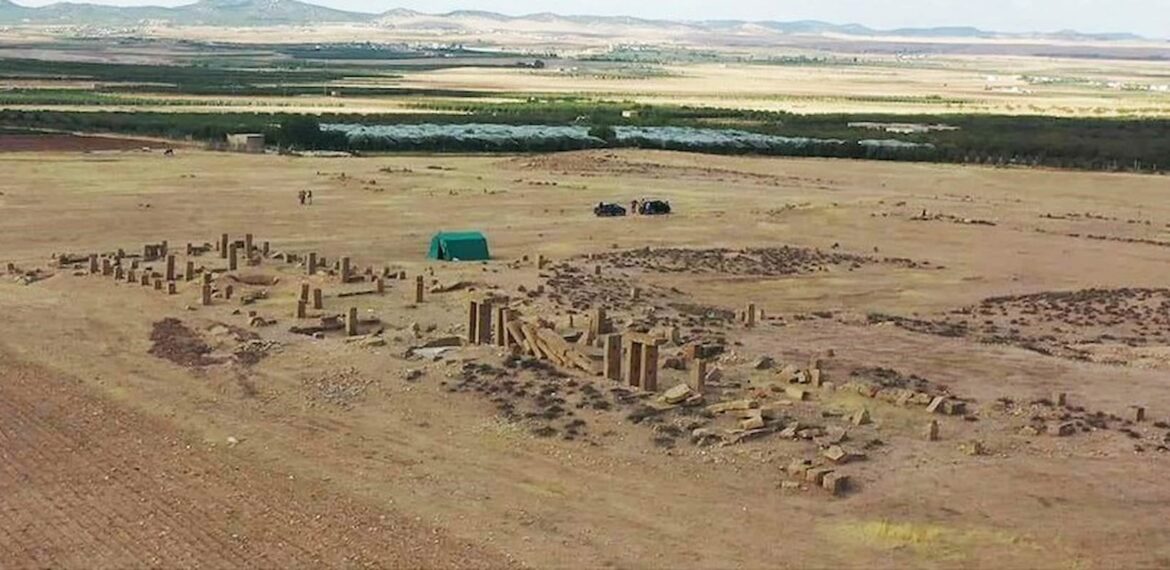

Location of Henchir el Begar. Credit: Università Ca’Foscari Venezia

Location of Henchir el Begar. Credit: Università Ca’Foscari Venezia

Among the sites drawing researchers’ attention, the one at Henchir el Begar stands out prominently. It has been identified with the ancient Saltus Beguensis, the nerve center of a vast rural estate located in the Begua district that in the 2nd century CE belonged to the vir clarissimus Lucillius Africanus.

The historical importance of the site is attested by a famous Latin inscription—CIL, VIII, 1193 and 2358—that transcribes a senatus consultum from the year 138 CE, which authorized the organization of a bimonthly market, an event of deep significance in the social, political, and religious life of the time. The settlement, extending across approximately 33 hectares, is structured in two main sectors designated as Hr Begar 1 and Hr Begar 2, both equipped with olive oil production facilities, a water-collection basin, and a diversified system of cisterns.

It is in Hr Begar 1 where the largest Roman frantoio discovered in Tunisia is located and the second largest in the entire Roman world, an industrial complex dominated by a monumental torcularium composed of twelve beam presses. A short distance away, Hr Begar 2 preserves the remains of a second production installation, somewhat smaller but equally formidable, equipped with eight presses of the same type.

Torcularium at Henchir el Begar. Credit: Università Ca’Foscari Venezia

Torcularium at Henchir el Begar. Credit: Università Ca’Foscari Venezia

Stratigraphic analysis and associated materials have determined that these macro-structures were operational between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, a fact that points to an exceptionally prolonged continuity of production, spanning periods of profound political and economic transformation. The surrounding area also contains a rural vicus where colonists and possibly segments of the local population resided, a residential space in whose surface numerous millstones and stone grinders have been documented, revealing a mixed agricultural production that combined grain processing with oil production, thus highlighting the dual agrarian vocation of the enclave.

Recent geophysical surveys using ground-penetrating radar have made it possible to map a dense network of residential structures and road traces previously unknown, revealing an organization of rural space with a complexity and articulation far greater than previously assumed for this type of frontier settlement.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

This archaeological mission is the result of a fruitful international scientific collaboration formalized in 2023 at the initiative of Professor Samira Sehili of the Université La Manouba in Tunisia and Professor Fabiola Salcedo Garcés of the Complutense University of Madrid.

The addition of Professor Luigi Sperti as co-director on behalf of Ca’ Foscari, supported by institutional recognition from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, strengthens the ties of scientific cooperation among the three nations and opens unprecedented prospects for joint research within the growing academic interest in the archaeology of production, particularly olive oil production—a defining element of Mediterranean civilizations whose imprint endures to this day.

Excavation work in the layers corresponding to periods ranging from the Byzantine era to the modern age has yielded movable finds of notable interest, among which one may highlight a bracelet decorated in copper and brass, a projectile made of white limestone, and several pieces of architectural sculpture, such as a fragment of a Roman press reused in a construction from the Byzantine period—an eloquent example of the long lifespan and continuous reuse of materials at the site.

This mission offers us an unprecedented perspective on the agrarian and socioeconomic organization of the frontier regions of Roman Africa, emphasized Professor Luigi Sperti. Olive oil was a product of paramount importance in the daily life of the ancient Romans, who used it as an essential condiment in cooking, as a body-care product in both athletic and medical contexts, and even—as in the case of lower-quality varieties—as fuel for lighting systems. Shedding light on the production, marketing, and transportation processes of this product on such a vast scale is an exceptional opportunity to combine research, heritage enhancement, and economic development, confirming the relevance of archaeology as a hallmark of excellence for our university.

Dining and Cooking