It takes barely an hour to reach the Gerovassiliou Estate from downtown Thessaloniki. As we leave behind the dense cityscape, the landscape rewards the eye with luminous greens of the season. Though Epanomi has become almost a suburb of the city, large stretches of the road still run through rich farmland and wild, enticing nature. Approaching the estate, you don’t quite know where to look first – you’re momentarily stunned. A triumphant vineyard spills across the surrounding hills and plains, fluid and harmonious, as if painted by a master’s hand – Cézanne, perhaps, or Pissarro, working with an inquisitive brush on a living canvas.

A vibrant work of art

“Look how beautiful the vineyard is,” Evangelos Gerovassiliou says as he welcomes us to the estate. We walk along the winding entrance path to fetch umbrellas from the visitor area, and he adds, “It’s nature’s own artwork – if you know how to cultivate it. Is there any other plant as beautiful?” We’ve arrived at an ideal moment of the year – late spring – when generous rains have farmers rejoicing in these long-awaited, thirst-quenching showers.

Brief introductions

In our exchanges before this meeting, Gerovassiliou sounded almost puzzled by my request for an interview. He’s a living legend of Greek wine – that’s my phrase, not his; he would never call himself that – and legends, one might think, need no introductions. Or do they? After all, every bottle that bears his label, whether from the estate or from one of the other wineries he oversees, is an introduction in itself. His wines are great wines – and not just in the Greek market, but internationally, too.

Still, for younger generations, introductions might be useful, so here goes: Gerovassiliou is one of the foremost figures in a field that has undergone tectonic shifts in recent decades. He belongs to the generation of winemakers who crafted wines of quality and, with patience and integrity, brought them to the lips of many. He is part of a generation that educated us in wine and filled us with pride for our own, one of a new, serious and upright entrepreneurial elite that rolled up its sleeves and worked to ensure that this important sector thrived.

In Gerovassiliou’s work – and in the work of a few others like him – we see an optimistic reflection of a country rediscovering its confidence. What is needed is to dare, to work, and to create. Standing on a historical threshold and making use of every intellectual tool available, his generation, with its rare mental resilience and deep historical grounding, did a remarkable job of applying everything they learned, both in the realm of agricultural and beyond.

[Yiannis Bournias]

[Yiannis Bournias]

A childhood in the fields

“I was born here in Epanomi. My father was orphaned at the age of two – his father was killed in the war in Asia Minor. His mother remarried, and his stepfather threw him out. A cousin took him in and, as a little boy, he sold eggs to get by. My mother came from a farming family. She was top of her class at school, but in fifth grade her father pulled her out to work in the fields. That’s how life was then. Maybe that’s why she was determined that her children would study – because she never had the chance herself.

“My parents met while working as laborers in the fields. They married with nothing, as my mother used to say. The only wedding gift they received was a small coffee pot. That’s how they started. They were hardworking people. They built their little house and managed to buy a few plots of land. My mother’s one and only goal was for her children to get an education. My older brother and I were both good students. He was admitted with honors in chemistry at the university in Thessaloniki, and I got into agronomy. I liked it – it felt close to what I knew, to the land. We had worked in the fields since we were little.

“I still remember it vividly: under a wild pear tree my parents had hung a swing for me while they worked. I played with butterflies and grasshoppers, with ladybirds and lilacs… My whole life was in the fields. Later, while I was still young, we kept two goats, two horses, a pig, some chickens. We were self-sufficient; we lacked nothing. We had our own milk, cheese, meat, eggs – and a pig for Christmas.

“I liked my studies in agronomy, but they didn’t fulfil me completely – I wanted something more. By my second year, I was already thinking about postgraduate studies. Then came a strange coincidence: my father’s wine had gone bad, and someone told me there was a chemist in Thessaloniki who made wine. I took him a sample to taste. He said, ‘The wine’s spoiled, but come see me during harvest time.’ When I did, I brought him some must, and he told me to add this and that. I asked him what those things were – I was an agronomy student, after all – but he said it was a secret. When I left, my mind started racing. I had to find out what it was. That’s how I discovered there was a school of oenology, and from my second year onward I set my heart on studying there – in Bordeaux, in France.

“My father was doubtful. ‘Why go abroad? Your brother’s already a chemist,’ he said. But I was unstoppable.”

Evangelos Gerovassiliou with his wife, Sonia Tziola-Gerovassiliou and their three children: Vassiliki, who leads marketing; Argyris, a talented oenologist; and Marianthi, who has begun taking on the management of the estate. In the background stands “Balancer”, a sculpture by George Lappas. [Yiannis Bournias]

Evangelos Gerovassiliou with his wife, Sonia Tziola-Gerovassiliou and their three children: Vassiliki, who leads marketing; Argyris, a talented oenologist; and Marianthi, who has begun taking on the management of the estate. In the background stands “Balancer”, a sculpture by George Lappas. [Yiannis Bournias]

Learning the Great Wines

“In Bordeaux, I discovered a world that embraced me. It was just after the fall of the dictatorship in Greece, and the French were very sympathetic towards Greeks at the time – there was Melina Merkouri, Theodorakis… They really welcomed me. I did well at school. My professor at the University of Bordeaux, Émile Peynaud – who was also the technical consultant at Porto Carras – said to me, ‘If you wish, I can arrange for you to work at Porto Carras when you graduate.’ And that’s exactly what he did; he took me under his wing and made me part of his team.

“His team included some major players, and we would visit the finest châteaux. We had access to things I couldn’t even fully appreciate back then. It was an extraordinary experience – we would take samples and taste wines straight from the great estates. Tasting, dégustation, was part of our studies. I couldn’t yet grasp the magnitude of the wines I was trying, but it was nonetheless a unique opportunity.

“What impressed me most in France was the work done in the vineyards, because in all great wines, the real work happens there. That’s why you saw our vines here looking the way they do. The vineyard gives you your raw material and your quality – if you know how to handle it. The oenologist doesn’t add anything; he must bring out the best qualities of the grape and seal them inside a bottle. That, for me, is the philosophy of a good winemaker.

“Oenology is a science – but there is also intuition, and what we call art. Everyone learns the same principles, yet some make great wines and others don’t. It’s like painting: everyone has brushes, but it’s intuition that tells you when to harvest, when to intervene, and how to handle the process. Often it comes down to the smallest of decisions – but those are what make a great wine. I saw all that in practice. It taught me a great deal.”

The legendary Porto Carras

“I started working at Porto Carras when I was 25; I was under Peynaud’s supervision for the first eight years. Porto Carras was a school in itself – not only for wine, but for life, for society. Mr Carras was a true gentleman, a man of ideals, of vision for his country and his people. He embraced everyone who worked there. He created Greece’s first integrated resort complex: an olive press, a winery, cold-storage facilities, bakeries; he had already created decades ago what we now call agritourism.

“He invited some of the best architects in the world to design the hotels, built the first golf resort in Greece, and turned the place into a hub of culture. Salvador Dalí came, Gina Bachauer played the piano and gave lessons there, and every year the World Youth Music Congress was held there. Everyone passed through – great personalities such as Niarchos, Mitterrand, Karamanlis, Rallis, Mavros, Papandreou… For me, it was an extraordinary experience.

“At Porto Carras I entered fully into the spirit of fine wine. It was the first estate in Greece with its own vineyards and a modern winery, and we produced great wines. The Blanc de Blancs became internationally known. We were making wines based on the French wine philosophy – revolutionary for Greece at the time. The Blanc de Blancs was Assyrtiko, the first Assyrtiko ever cultivated outside Santorini. Back then, Santorini wines were rather heavy, slightly oxidized. In 1974, Assyrtiko arrived at Porto Carras, and we made fresh, fruit-forward wines like those of today – but at the time it was a revelation.

“Because those wines had naturally high acidity, they weren’t easily accepted in Greece then. People found them too sharp. They were ahead of their time. But Porto Carras had such prestige – its wines were sold at Harrods – that it inspired others to follow. I remember Yiannis Boutaris and Tsantalis coming to see the winery. It was the first to be built according to French standards: a four-level design by architects from Marseille, equipped with the most advanced technology available.

“I truly believe Porto Carras played a decisive role in the development of Greek winemaking. It was the first experimental and demonstrative vineyard of the Wine Institute and the University of Thessaloniki for international grape varieties. At that time, foreign varieties were officially prohibited in Greece. Averoff had secretly planted Cabernet, but no one else had done it openly. When the experiments at Porto Carras succeeded, the Vine Institute and the Department of Agriculture granted permission to import foreign varieties – Cabernet Sauvignon and others. Porto Carras opened that door.”

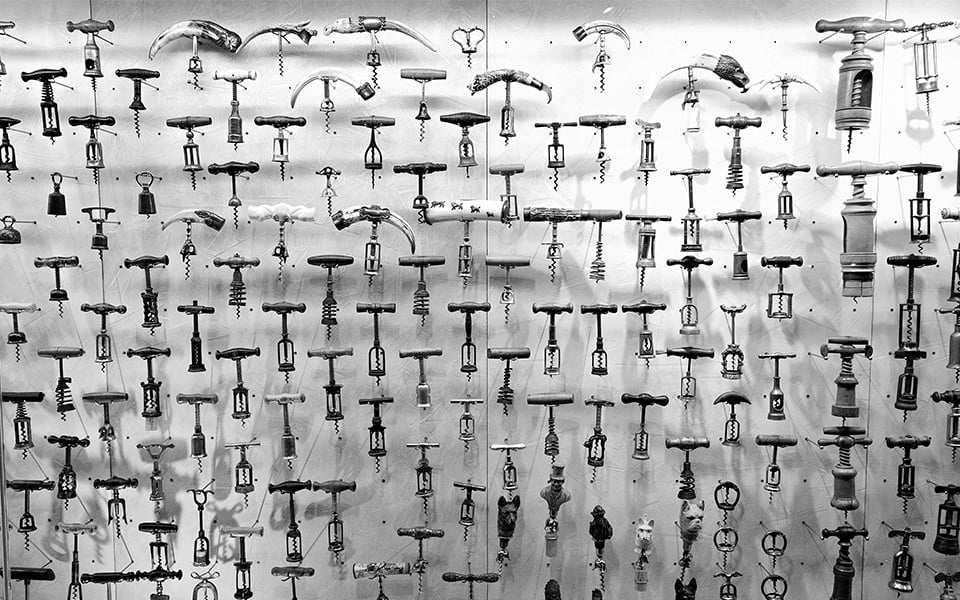

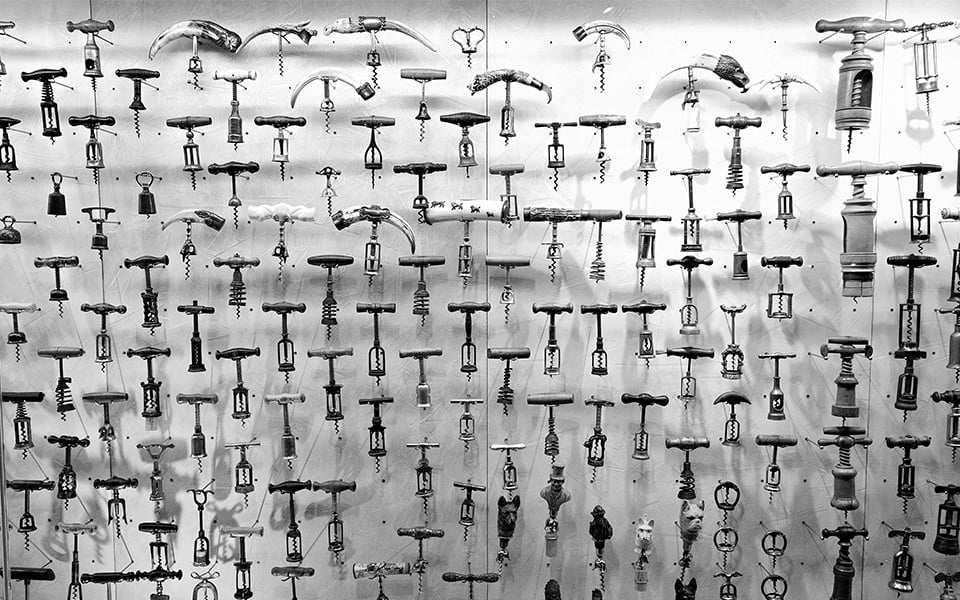

More than 2600 corkscrews, forming one of the world’s largest collections of such items, are on display at the Wine Museum Gerovassiliou. [Yiannis Bournias]

More than 2600 corkscrews, forming one of the world’s largest collections of such items, are on display at the Wine Museum Gerovassiliou. [Yiannis Bournias]

The rescue of Malagousia

“At Porto Carras we managed to save the Malagousia grape variety. I realized it had great potential, so we gradually increased its numbers – from just four or five vines to four hectares within three or four years – and produced the first wines. I saw that this was a variety with a future, and I said to myself, I’ll work with it, too. So I planted a small vineyard here in Epanomi, at the same time as I was still at Porto Carras.

“When I first started working with Malagousia, I truly believed in it. Nobody knew it back then. But I felt it was worth dedicating myself to. When I planted it here and began making my own wines, I traveled all over the world – for exports, to meet journalists, to let people discover it. It wasn’t easy. It took ten to fifteen years before the name ‘Malagousia’ began to be heard.

“In 1986 I made my first Assyrtiko-Malagousia blend here, called Beau Soleil. It was a great success – four or five thousand bottles sold immediately. Gradually I began buying land, adding one or two hectares every year, all planted with Malagousia. From 1981 to today, over 45 years, I’ve kept expanding the estate – every time buying a new plot, planting Malagousia or something new. Today we’ve reached 120 hectares.”

The other wineries

“In 1989, Vassilis Tsaktsarlis – one of the finest oenologists in the world and now my partner at Biblia Chora – left Lazaridis, where I had first helped him get started as a young winemaker. We decided to create the Biblia Chora winery in the region of Kavala. We began modestly, but the potential for quality there was enormous. It went – and is still going – extremely well. We now have 80 hectares and a beautiful winery, producing a range of outstanding wines.

“At the same time, we decided to invest in other parts of Greece that weren’t yet well known. We went to Goumenissa, where we bought Titos’ small estate – a beautiful property – and started producing Goumenissa wines. Then my friend Christos Kokkalis, who owned the Trilogia Estate in Ilia, asked me to take it over and develop it further. It was a wonderful place. We bought it, renamed it Ktima Dyo Ipsi (‘Two Heights Estate’) – and now we produce Monologos, Dialogos and Trilogia: remarkable wines.

“In Santorini we collaborated with the exceptional local oenologist Ioanna Vamvakouri. Because the island is already full of wineries, we chose to go just across the water, to Thirasia – which has the same soil and climate quality – and there we started a very difficult venture. We built a small winery in the face of immense challenges: no transportation, no water, no electricity, nothing. The investment cost was four times higher than anywhere else. Yet we created a small miracle: the organic wines of the winery Mikra Thira, which in no time began receiving major awards and are doing extremely well.

“Here at the Epanomi estate, we have 86 permanent employees, 130 in total with the seasonal workers. Counting all the wineries together, we’re around 300 people. Vassilis has two children – both studied oenology in Bordeaux and have just joined us. They’re excellent. Sonia and I have three children, and they’re all involved in the work, too: Argyris is an oenologist, Marianthi is a lawyer and Vasiliki works in marketing. Between us, we’ve covered the full spectrum.”

The climate challenge

“The changes in the climate over the past 15 to 20 years have been dramatic. We now have fewer but much more intense and sudden rainfalls. Three years ago, we had 200 tons of water per 0.1 hectare – the first time in history, something like the 2023 floods in Larissa. That’s why we changed the way we cultivate. We now leave the vineyards untilled, with the grass growing between the rows, so that the soil doesn’t get washed away. And we avoid heavy leaf-thinning so the vines don’t burn in the sun. Science helps us, as does experience. But we must take precautions and respect nature.

“At some point, agriculture must become more rational: water should be used only for productive cultivation – not for subsidized crops that yield nothing. Let’s not forget that agriculture accounts for 86% of total water consumption. Real farmers understand this instinctively, but many just set up a sprinkler and water in the middle of the day. How can you do that at noon? Sixty percent of it evaporates! That must stop. The water issue is critical; we need to save it. Some say desalinated water is a solution – but it’s not a good one. Quality desalinated water is very expensive, and often not suitable. I’ve seen it in Santorini; it can add unwanted salts to the soil. The real solution is to protect our groundwater, and to use water wisely, only where it’s truly needed.

“It’s very hard for any government to confront the farmers. They’ve grown accustomed to subsidies – it’s a long-standing issue. When you know you can block a road with your tractor and end up getting compensation or a grant, you’ll keep doing it. But the purpose of agriculture is to find solutions for production. Production is what will save us.

“One positive thing we have is that Greek grape varieties are ancient and are capable of adapting naturally to climate change. Look at how resilient the Assyrtiko of Santorini is – it thrives in conditions that are almost desert-like. So it’s a variety that can survive almost anywhere. The Limnio, a grape mentioned by Aristophanes in the 4th century BC, still exists today. That means it’s resilient and will endure all weather extremes. And, of course, we don’t imagine this place turning into a desert – but we will have water problems. It’s a viticultural challenge. There are rootstocks resistant to drought, there are suitable varieties. Right now, we have forty different varieties in our experimental vineyard – that’s what we’re working on: discovering which ones will endure the changing climate.”

A model winery

“I’m proud that, because of us, five new small-scale wineries have been created in our village and, in the wider area, another seven. I’ve even met people from Crete who tell me, ‘We saw you as a model and dared to start our own.’ I’m happy that a whole movement of small producers has emerged – possibly inspired by us and our style – and that they are all satisfied with what they’ve achieved.

“Greek wine has a great future, in my opinion. Our native varieties are becoming known; the Greek brand name is being built; there’s plenty of room for growth. I see the future as very positive. In recent years, young people have started to get involved. There are now European Union programs that provide funding. One must take advantage of these opportunities and have the courage to try. The challenge, though, is that the best vineyard areas are far from Athens and Thessaloniki. You have to move to the countryside, to decentralize. And I’m not sure how many young people want to live there. But there are some who dare.”

Epilogue

While the winemaker has been telling me all this, we’ve been walking, first on roads through the vineyard, then through the bottling and packaging areas, and then down into the cellars where the wines mature.

We’ve also visited the unique Wine Museum, and heard the stories it whispers into the ear of the inquisitive visitor – stories about the world of wine: the ancient symposia and how the Greeks drank their wine, the methods and materials used for transporting it through the centuries, viticulture and the crafts of barrel-making and cork-cutting.

It’s a beautiful museum, home to so many fascinating objects – from decanters and ancient amphorae to pumps and presses. There’s also a rare collection of 3,000 corkscrews from different eras and different lands, which the winemaker assembled during his travels; those journeys shaped him and deepened his love for wine.

At one point, we stop before a horizontal display case. “A Swede, in 2011, when all the Europeans were insulting us and calling us lazy, wrote this,” Gerovassiliou says, inviting me to read the notice in the case:

“My wife and I wanted to make a donation to Evangelos Gerovassiliou and the Wine Museum. Nowadays, many speak of Greece’s debt to Europe, but they forget Europe’s debt to Greece. I will mention only this: Democracy, Art, Wine. I have chosen six different corkscrews, all inspired by wine and Greek mythology.”

“He found them and sent them to me. Isn’t that deeply moving?”

We pass through courtyards and gardens, admiring impressive sculptural works by important Greek and foreign artists, planted among the vines and around them. This open-air gallery – rare and remarkable as it is – still cannot compare to the impeccably groomed vineyard itself, the ultimate work of art.

My visit ends in the tasting room. We swirl and sip the Malagousia, the white Estate blend (Malagousia-Assyrtiko, another Gerovassiliou “invention” that inspired many), and the outstanding Syrah. The room is packed with people – Greeks and many foreigners. It’s an ordinary Friday. An American couple is looking for somewhere to sit; Gerovassiliou signals to his staff to bring an extra table for them.

I watch, I taste, and I reflect on the man: ten lives in one, lived in another world entirely – densely woven, full of promise. A maker of wines that are works of art, a creative soul that has offered so much to society.

Angelos Rentoulas is director of the gastronomy publications of Kathimerini. This interview was first published in Gastronomos, Issue 233, June 2025.

Dining and Cooking