Two recent news events in Hawai’i highlighted the vulnerability of the state’s food supply, both raising the specter that a future disaster could place us at risk of starvation, located as we are in the far reaches of the ocean.

Last week, Civil Beat reporter Thomas Heaton covered a conference in Wahiawā where scores of worried participants warned that the failure to support state agricultural production could put local residents at risk, pointing to the Maui fires and covid epidemic shortages as vital wake-up calls.

A few days later, his colleague Jeremy Hay examined a proposed city charter amendment that seeks to help replenish local food bank coffers by setting aside tax money to strengthen local food production. Federal spending cuts are underscoring the urgency of ensuring Hawai’i has its own supply to be able to feed the poor, the proposal’s advocates said.

But what if something even worse happened?

Ideas showcases stories, opinion and analysis about Hawaiʻi, from the state’s sharpest thinkers, to stretch our collective thinking about a problem or an issue. Email news@civilbeat.org to submit an idea or an essay.

How about if the ships we depend upon to deliver most of our food stopped coming almost entirely, and didn’t come back for years?

That’s an almost forgotten piece of history here in Hawai’i, overshadowed as it is by the further explosion of violence that came to be known as World War II. I stumbled upon this story while doing research at the Library of Congress, where I found a copy of Ralph Kuykendall’s eye-opening 1928 book, “Hawaii in the World War,” co-authored with Lorin Tarr Gill, the mother of a noted Hawaiʻi environmentalist of the same name.

What happened in World War I seems almost unimaginable today. Now at least nine supply ships rotate food and other goods to the islands, including three each week to Honolulu, bringing the basic goods we need to survive. About 90% of what we eat is imported from somewhere else.

Our recent shortages, from the fires and the pandemic, ended up more as inconveniences than existential risks to our survival. But World War I, which lasted four years, from 1914 to 1918, was something quite different.

World War I started far away, in Sarajevo. In July 1914, a Serbian nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire. This provoked a chain of events that led to imperialist and militaristic countries around the globe grabbing at each other’s overseas possessions and squabbling over border lands each claimed to own.

The bottom line was that two big power blocs collided. On one side were the Germans, the Austro-Hungarians and the Ottoman empire. On the other side was the British empire, with its raft of colonies, including Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and India, along with the Russians, the French and the Belgians. The Japanese empire joined the war as allies of the British. All this led to the barbarity of what was called the Great War.

America at first tried to stay out of it but eventually everyone had to pick a side.

In 1914, when all this started, Hawai’i was a territory of the United States, governed by a political appointee, local businessman Lucius Pinkham, who had been named to his post by President Woodrow Wilson.

Hawai’i’s most vocal defender in Washington was its congressional delegate, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole, who had already served more than 10 years in office. Hawaiʻi wasn’t a state so Kūhiō had to do the best he could without having a formal vote.

Hawai’i was already getting jerked around a good bit by Washington. Its infant tourism industry was restricted by government-imposed shipping rules that limited passenger traffic and made it hard for everyone, even Kūhiō himself, to get to and from the islands.

Sugar, Hawai’i’s most important industry, had been whipsawed by shifting ideological winds in Washington. The Republicans had used tariffs to protect the sugar industry and workforce but the Democratic party, which came into power in 1913, removed the tariff duties to allow cheaper sugar to be imported from lower-wage countries. The sugar industry in Hawai’i started to collapse and many people in the territory were thrown out of work.

In other words, there was economic distress in Hawaiʻi agriculture even before the war broke out.

Hawai’i was affected by the hostilities almost immediately. Three of the belligerent nations involved in the war — Great Britain, Japan and Germany — had naval and merchant fleets in the Pacific. Some German vessels fled for safety to Hawaiʻi because the United States was at first maintaining its neutrality.

Eventually 11 German ships showed up in Hawai’i, including two warships and nine merchant vessels, seeking shelter, almost all of them in Honolulu, occupying precious pier space and anchorage, according to Kuykendall and Gill.

From November 1914 to January 1917, the German ships sat in the harbor while people in Hawai’i wondered what to do about them. The U.S. military refused to free up the space by allowing them to anchor instead in Pearl Harbor.

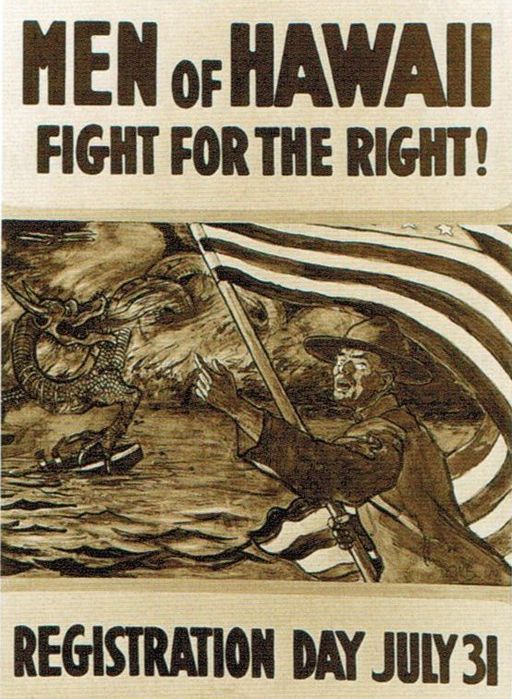

A World War I recruiting poster in 1917 urged Hawaiʻi residents to help in the war effort. (Wikimedia Commons)

A World War I recruiting poster in 1917 urged Hawaiʻi residents to help in the war effort. (Wikimedia Commons)

As it turned out, that was probably a good decision because in January 1917, as it appeared increasingly likely that the U.S. would enter the war, the ship’s commanders, under orders from Berlin, began sabotaging their own ships and perhaps planning to scuttle them and block the Honolulu harbor, according to Kuykendall and Gill. Eventually the U.S. government seized the ships.

The first people from Hawai’i who died in the war were sailors who lost their lives on April 1, 1917 when the armed American merchant ship SS Aztec was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat near France during a frigid hailstorm. There were six Hawaiians on board. Five of them died and only one, Charles Nakao of Hilo, survived.

Nakao wrote a vivid account of what had happened to him that appeared in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1917. He made a special point of thanking Queen Liliʻuokalani for her “kindly remembrance to us boys.”

Within a week, President Wilson went to Congress for a declaration of war. Many people in Hawai’i rushed to sign up to fight. Hawai’i’s Filipinos enlisted in particularly large numbers and by the end of 1916, they made up half of the state’s National Guard. Other Hawai’i residents were more reluctant or were opposed to the war.

The United States turned to the draft. Ultimately some 10,000 Hawai’i residents served in American forces in the war. More than 100 died.

Officials in Washington warned Hawai’i that it was on its own, and that in fact, Hawai’i would be asked to help feed others as well.

“Please urge upon your people fullest possible use of all land this year,” Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane wrote, according to Kuykendall and Gill. “Make yourselves as nearly self-supporting as possible in food-stuffs and increase your surplus available for continental consumption.”

Hawai’i, which imported much of its food even then, had to re-learn to provide for itself.

This necessity became more evident in the late fall of 1917, when the federal government commandeered the fleet of the Matson Navigation Co. and sent the ships off to the Atlantic theater. American-Hawaiian Steamship Co.’s fleet was also seized.

“In brief, the Pacific was stripped bare of every American vessel that was at all suitable for the Atlantic service,” Kuykendall and Gill wrote, calling it a “general derangement of shipping.”

Matson spokesman Keoni Wagner declined to comment for this column but an account of Matson’s history on the company website says the ships were requisitioned as troopships and military cargo carriers and were only returned to civilian duty after the war concluded, which happened in 1919.

Some trade was restored when smaller ships were sent to Hawai’i from the West Coast because people on the continent wanted Hawai’i’s sugar, rice and bananas.

Hawai’i’s residents had to make a lot of changes, and they did.

People who didn’t know how to farm had to learn to do so. People had to eat foods they didn’t like. People had to find a way to survive as groceries became increasingly expensive amid food shortages. Some people went hungry.

Farms were set up on school grounds and children were taught how to plant crops. Farmers were told to shift their production to food crops as much as possible. Wheat flour was hard to come by, and families were urged to make bread instead from starchy vegetables like breadfruit. Banana bread became a home staple.

On the other hand, sugar had a resurgence.

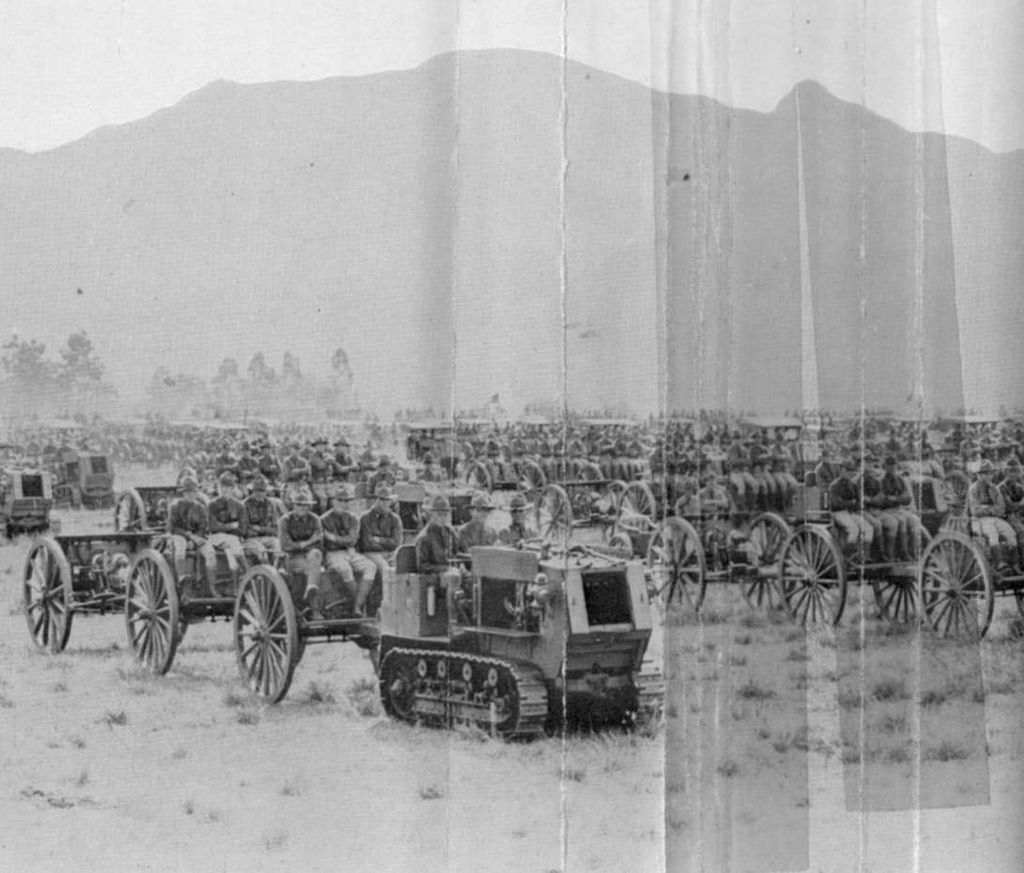

The 11th Brigade was based at Schofield Barracks during the first world war. (Wikimedia Commons)

The 11th Brigade was based at Schofield Barracks during the first world war. (Wikimedia Commons)

There was considerable hardship. At times, the shortage of rice, Hawai’i’s most important food staple, became a crisis.

Native Hawaiians were particularly hard-hit. In his book, “Hawaii: Eight Hundred Years of Political and Economic Change,” historian Sumner La Croix reported the prices for poi and fish doubled, underscoring to many Hawaiians their increasing economic insecurity.

This was part of the impetus for Kūhiō’s more intense advocacy for the Hawaiian homestead program, which became the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, enacted in 1921. He wanted to make sure that if food shortages ever came again Hawaiians would own single-family homes with enough land that they could grow some of their own food and never again be so dependent on others.

If Hawai’i could get cut off once, it could happen again. It may be inevitable.

In the meantime, it will help if we support our own agricultural economy and buy the things our farmers grow and sell, even if it costs more money. They are our most vital lifeline. In a time of famine, they may be our only food providers. And we will also need them to teach the rest of us how to farm.

Hawai’i’s rich land, its climate and its abundant natural resources, may help protect us, too.

Paul Brewbaker, a Hawai’i economist and historian who is the son of a corn scientist, thinks Hawai’i residents can be resilient when they need to be. He notes that Hawai’i has some 2 million acres of agricultural land left untended since the collapse of the sugar industry, fields he thinks could be converted to productive agriculture if it should become necessary.

He noted that Hawai’i turned to corn for subsistence during World War I. At the end of the conflict, some 10,000 acres of corn had been planted in Hawai’i, more than at any other time, he said, and it became a primary food source.

That could happen again. Brewbaker pointed out that in Hawai’i, it takes only 70 days for sweet corn to grow and be harvested.

“That’s the beauty of the tropics,” he said.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign Up

Sorry. That’s an invalid e-mail.

Thanks! We’ll send you a confirmation e-mail shortly.

Dining and Cooking