In 2007 Paula Rego realised she had a drink problem. But not the obvious one. The realisation came to the Portuguese painter, one of the most famous living artists in Europe at the time, not with a blinding hangover but a legal dispute.

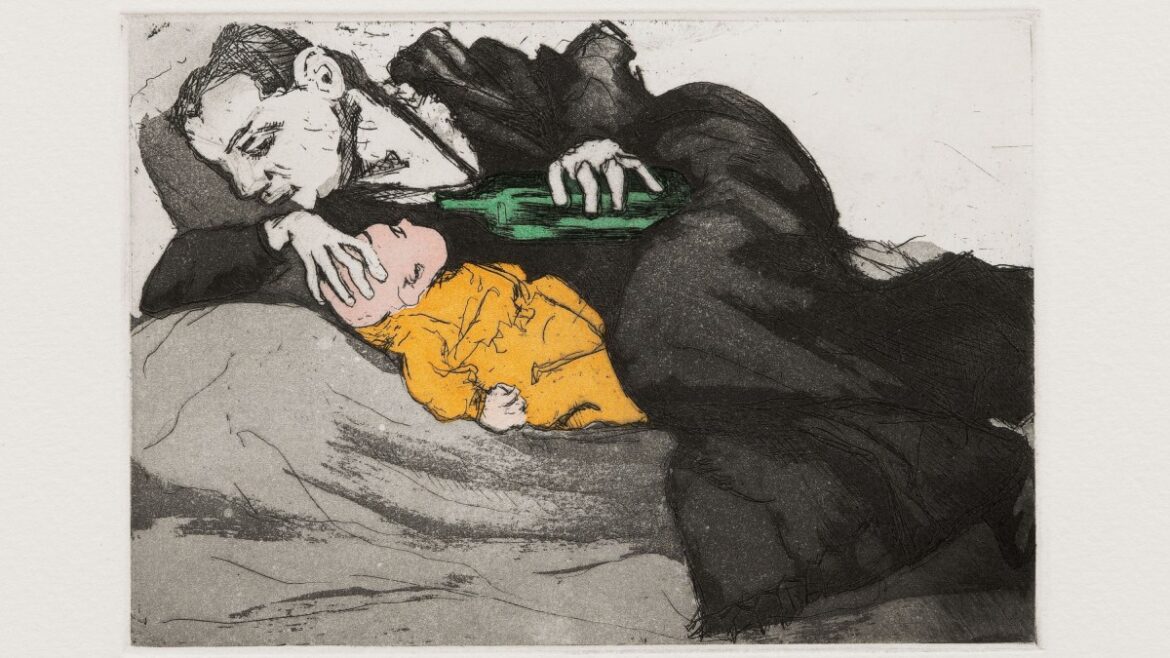

Rego had been commissioned that year to design a set of wine labels for the vintner José Roquette, the owner of the celebrated Esporao vineyard in the Alentejo region of southern Portugal. What she delivered was a series of outrageous etchings of drunken debauchery that incensed her client and were never put on bottles but can now finally be seen in Paula Rego: Drawing from Life at the Cristea Roberts Gallery in London.

She saw the potential in the subject matter. “Wine is very popular, wine is for everybody: babies are brought up on a soup of wine — wine with bits of bread in it — so that they sleep well,” she recalled. “I thought, I will make it a bit naughty: these mummies giving their babies wine not in little bowls but bottles, as if they were giving milk.” That was the least of it. The six hand-coloured labels feature wives coping with drunken husbands, children slumped next to empty bottles and baby seats used as wine racks.

Two Loves, 2007

ESTATE OF PAULA REGO. COURTESY OSTRICH ARTS LTD AND CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY

An etching by Paula Rego for vintner José Roquette, 2007/2020

ESTATE OF PAULA REGO. COURTESY OSTRICH ARTS LTD AND CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY

In Portugal, during the 20th-century dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, wine was used to anaesthetise the public (football was the other drug). In exposing this, Rego’s pictures are similar to William Hogarth’s Gin Lane print, which depicts the evils of gin consumption in 18th-century London. As wine labels they are completely counterintuitive, similar in effect to the government health-warning shots of diseased smokers that now feature on cigarette packets. And as Roquette understood instantly, they hardly endorsed his product.

• The best exhibitions in London and the UK

The winemaker sent the designs to a lawyer. “His legal opinion concluded that Rego’s drawings for the wine labels would constitute a criminal and civil offence, potentially leading to sanctions,” recalls Rego’s son, the film-maker Nick Willing. “He assessed that the drawings could be interpreted as encouraging irresponsible drinking.”

The project promptly collapsed. Rego, however, saw the funny side of the debacle: “They wanted to pretend that wine doesn’t make you drunk, which of course it does,” she told the art critic Tom Rosenthal. “I loved that about wine.”

Rego herself had a complex relationship with drink. “She wasn’t an alcoholic. But Mum drank too much wine in periods of her life,” Willing says. I meet him in Rego’s old studio, inside a Victorian carriage house on a leafy cobbled lane in Kentish Town in north London. It’s like being in the set-design department of an opera house. There are mannequins of ogres, gnarly bits of Victorian furniture, trays of pastels and paints, costumes of every variety. A self-portrait dummy of Rego — wearing a widow’s dress and a glowering expression — is the stuff of nightmares.

Paula Rego with her son, Nick Willing

©NICK WILLING/BBC

“She suffered very badly from depression and wine is a depressant,” Willing says. “On the one hand she wanted to alleviate herself and on the other she obviously recognised that the next day she would be even more in the doldrums. She would start drinking just before dinner. In other words, she was like any middle-class English person in Islington.” But there were also periods when Rego would be teetotal. And in later life she limited herself to a celebratory glass of champagne at the end of a day’s painting.

• Can art improve your mood? I went to the Courtauld to find out

Rego was born in Lisbon in 1935 into an affluent liberal family quietly getting by under the watchful eye of the Salazar regime. She began making prints in the 1950s, setting up a printing press in the wine barn on her grandparents’ farm. Some of her early works were slightly critical of Salazar, but she didn’t print them because she was terrified of the secret police. Later, printmaking was a way in which she could explore societal ills and folkloric themes, with the potential for widespread dissemination of the images.

From 1957 to 1974 Rego lived in the fishing village of Ericeira, some 40km north of Lisbon, where she and her husband, the British painter Victor Willing (whom she met while studying at the Slade School of Fine Art in London in 1952-56), brought up Nick and his two sisters. Wine was a staple of family life. “One of my duties as a youngster was to take the five-litre garrafão down to the taverna in the village and have it filled at nine escudos a litre — that was about 14p in those days. We all drank that rough stuff at dinner, our teeth turning purple,” Willing recalls. “I started drinking it when I was 13. It was disgusting, made your poo go green.”

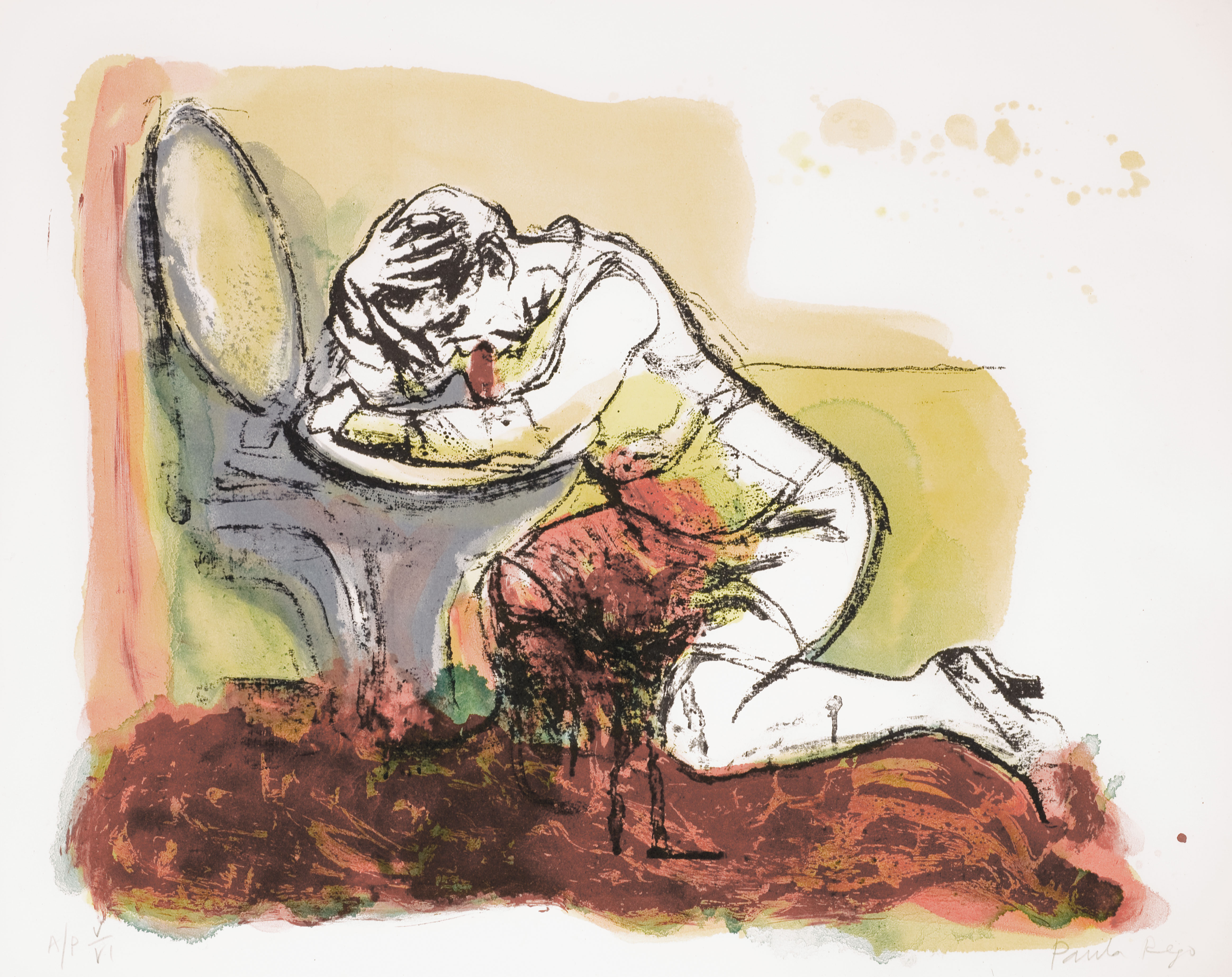

Retch, 2007

ESTATE OF PAULA REGO. COURTESY OSTRICH ARTS LTD AND CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY

The family subsequently moved to London. From Britain, Rego critiqued — and painted — the myriad predicaments felt by the Portuguese people under the dictatorship. Her feminist principles and printmaking skills would combine in her celebrated Abortion Series of graphic works from 1998-99. “I sometimes refer to her as the conscience of Portugal,” Willing says.

Rego is not the only artist to have worked for winemakers. Salvador Dalí, David Hockney and Andy Warhol designed labels for Château Mouton Rothschild, while Yoko Ono drew a label for a 2005 vintage of Chianti Classico Casanova. In commercial terms, Rego’s addition to this niche in art history was unsuccessful, but artistically she created a series of gothic gems.

Willing unwraps the original copper plates of the labels, each one the size of a playing card and delicately etched with a cobweb of fine lines. “The idea of showing children getting drunk? That’s outrageous,” he says, peering into the grooves. “She’s subversive.”

Although etched in 2007, having been scorned the plates were put to one side and not printed until 2020, two years before the artist’s death. “At one point she was giving them away as gifts. They sort of remained quite personal,” says Gemma Colgan, a co-director of the Cristea Roberts Gallery.

Playtime, 2007

ESTATE OF PAULA REGO. COURTESY OSTRICH ARTS LTD AND CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY

One of Rego’s designs for vintner José Roquette, 2007/2020

ESTATE OF PAULA REGO. COURTESY OSTRICH ARTS LTD AND CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY

In the immediate wake of the Roquette farce, Rego was drawn into another unlikely wine-stained collaboration. She executed a series of lithographs on the same theme, also on view in London, works to illustrate a short story by the Portuguese novelist João de Melo about the pleasures of wine.

In O Vinho de Melo evoked the days and nights of a melancholy bookkeeper who lives for his lunch breaks and evenings spent drinking in the local tavern. “I drink my glass of red wine, gaze at the lights of Lisbon, listen to the heart and look at the humanity of the day,” the accountant says with a sigh.

Rego riffed on the tale with yet more grotesque imagery. Seemingly a romantic celebration of getting tipsy and the bonhomie of barflies, de Melo’s story also, albeit obliquely, broaches the numbing effects of wine. And that was what interested Rego. She married pictures of men slumped drunk and women vomiting into sinks and lavatories to this sentimental homage to plonk. “It’s not quiet and sweet, is it?” Colgan says. “There’s nothing fluffy about them. She’s really working through things that essentially relate to her own experience.”

• Read more art reviews, guides and interviews

The six label etchings are being sold as a set for £28,000, the lithographs range in price from approximately £2,000 to £3,000 each, and the gallery has several pencil sketches for Retch (each offered for between £12,000 and £22,000). So, who are the buyers? Why would someone want a drunk on their wall? “It’s a prestige part of art history, how important Paula is. That’s what I think collecting is about,” Colgan says. “Two or three years ago, the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York both bought a full series of her abortion prints. The Met is having a show of her work in 2028.”

Rego became a national treasure in Portugal, while in Britain she was made a dame in 2010. And her posthumous, ever-growing reputation has now brought about a further twist to the wine story, as Willing explains: “I was surprised to hear last year that Roquette’s son, who now runs the wine label, asked if he could use the labels after all. That’s very Portuguese: full of contradictions.” One can imagine Rego laughing and raising a glass to the idea.

Paula Rego: Drawing from Life is at Cristea Roberts, London, to Jan 17, cristearoberts.com

Dining and Cooking