Summary

The olive harvest in Greece is facing a crisis due to below-average yields caused by late-autumn rains and humidity, leading to significant damage to olive fruit and a potential 30 – 35% decrease in production compared to the previous year. Proliferation of pests like the fruit fly and gloeosporium has caused widespread damage in some regions, with some farmers resorting to joint milling practices to address labor shortages and processing challenges.

The year’s olive harvest is unfolding as a crisis in Greece, as initial projections for a below-average olive oil yield increasingly become reality.

We are likely experiencing the worst olive oil season in 30 years.- Yiannis Iliadis, Messenia olive oil millers’ association

The impact is most severe in the country’s southwest, where late-autumn rains and elevated humidity have fueled pest outbreaks that have significantly damaged olive fruit.

“We are likely experiencing the worst olive oil season in 30 years,” said Yiannis Iliadis, a mill owner from the village of Andania and head of the olive oil millers’ association of Messenia in the Peloponnese.

“The fruit fly and gloeosporium have taken a heavy toll on the season’s fresh olive oils,” Iliadis added. “The olives have already started to rot, and producers are rushing to extract whatever quantity of olive oil they can.”

Messenian olive farmers and producers said state-run crop-dusting operations to control the olive fruit fly were carried out too late this year, allowing the pest population to multiply during the summer and inflict widespread damage.

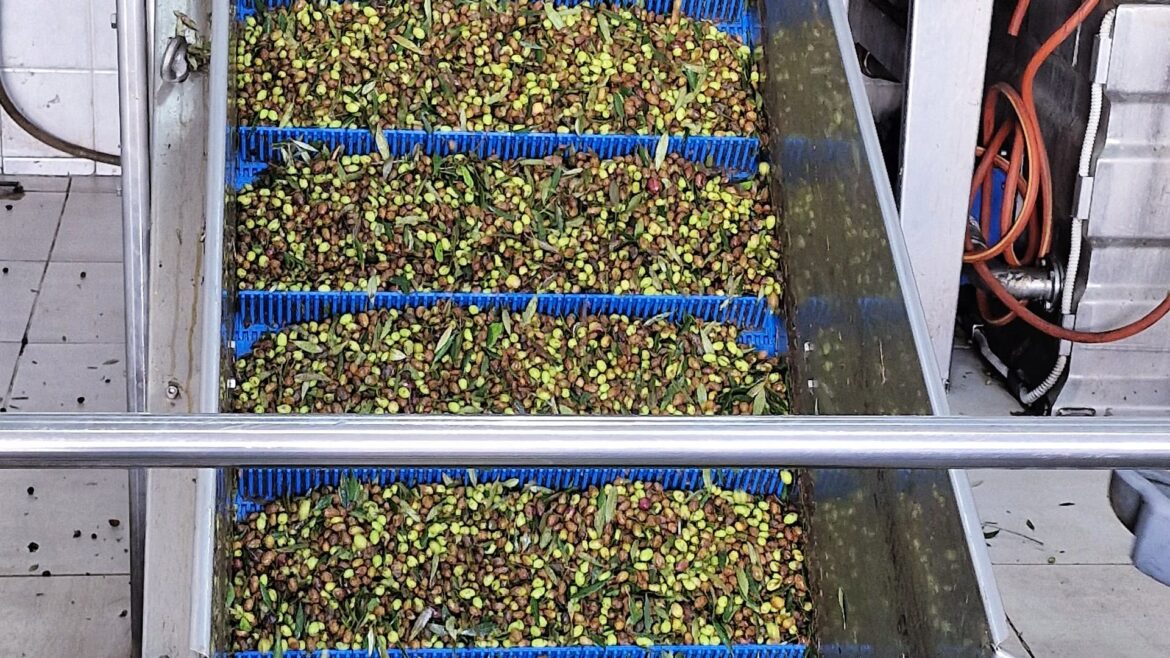

Koroneiki olives and olives infected by the gloeosporium (brown olives) being processed at a mill in the Peloponnese (Photo: Costas Vasilopoulos)

Koroneiki olives and olives infected by the gloeosporium (brown olives) being processed at a mill in the Peloponnese (Photo: Costas Vasilopoulos)

The agricultural association of Chandrinos in central Messenia has also filed a lawsuit against those responsible, arguing that delayed pest-control measures exacerbated the crisis and caused significant financial losses.

In nearby Strefi and Aristomenis, millers reported acidity levels in some freshly produced olive oils ranging from 1 to 2, and even higher.

“We have even seen olive oils with acidity above two degrees this season due to pest damage,” local millers said. “We need colder winters, which unfortunately are no longer coming.”

Olive oil acidity — the level of free fatty acids present in the oil — is a key indicator of quality. Oils with acidity up to 0.8 percent may be classified as extra virgin, the highest quality grade, provided they also meet the required sensory standards.

Producers said their biggest concern this year is gloeosporium, a fungal disease that causes olives to rot and become unsuitable for processing.

The fungus proliferates rapidly under mild temperatures and high humidity, causing olive anthracnose, which leads to fruit rotting and mummification and can severely compromise olive oil quality.

However, pest damage has not been uniform across Messenia, with some areas largely spared.

“Our fresh oils have an acidity of 0.3, which shows that quality remains high this season,” said olive farmer Ilias Koroneos from the village of Lambena.

In neighboring Ilia, in the western Peloponnese, harvesting also began earlier than usual to minimize pest-related losses.

Local agronomist Panagiotis Gourdoumpas said gloeosporium has spread to olive groves at higher altitudes, threatening oil quality and forcing producers to rush their olives to the mills.

He added that olive oil production in Ilia is expected to fall by 30 to 35 percent compared to last year, due to pest pressure and the natural production cycle following a strong 2024/25 season.

Olive pests have also intensified pressure on growers in Aetolia-Acarnania in western-central Greece, where gloeosporium infestations have caused extensive fruit drop.

Aetolia-Acarnania is among Greece’s most important olive-producing regions, cultivating mainly Koroneiki olives as well as Kalamon (Kalamata) table olives, which are also widely used for olive oil production.

“Producers in other regions were hoping for rain, but for us the heavy rainfall had the opposite effect,” said miller Dimitris Gantzoudis, who operates an olive mill in Stamna, north of Mesolonghi.

“October rains combined with mild temperatures favored the spread of gloeosporium, with devastating consequences for both quality and quantity,” Gantzoudis added.

He said many producers are harvesting as early as possible to limit further damage and shorten the season, while some have abandoned harvesting altogether.

Gantzoudis also said labor shortages have forced him to adopt milling practices more commonly used in Italy and Spain.

“Due to the lack of workers, we cannot process each producer’s olives separately,” he said. “Instead, we purchase the olives and process them together based on quality.”

Joint milling remains rare in Greece, where olives are traditionally processed separately due to the fragmentation of olive groves, with millers retaining a percentage of oil as payment.

“The challenges we face require adaptation,” Gantzoudis said. “Labor shortages and abnormal weather conditions are our biggest problems, and they are unlikely to disappear anytime soon.”

Dining and Cooking