The study is registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03335644 and is conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (IRB-Inserm) and the “Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés” (CNIL n°908450/n°909216). Each participant provides an electronic informed consent form before enrollment. This research does not result in discrimination in any kind to our participants.

Study population

This study relied on the data from the French NutriNet-Santé prospective e-cohort, launched in 2009, to investigate the association between nutrition and health46. Participants aged 15 and above are invited to participate in the study via a dedicated web-based platform (https://etude-nutrinet-sante.fr/) and regularly answer questionnaires on their dietary intakes, health, anthropometric47,48, physical activity49, lifestyle, and socio-demographic data50. Sex was self-reported by participants. No compensation was offered to the participants. The term “sex” is used throughout the study as we aimed to reflect the biological attribute rather than the gender shaped by social and cultural circumstances. There was no specific hypothesis of an interaction between studied preservatives and sex, thus results are presented overall. However, all cut-offs for exposure categories were sex-specific (and presented by sex in Supplementary Table 6).

Dietary data collection

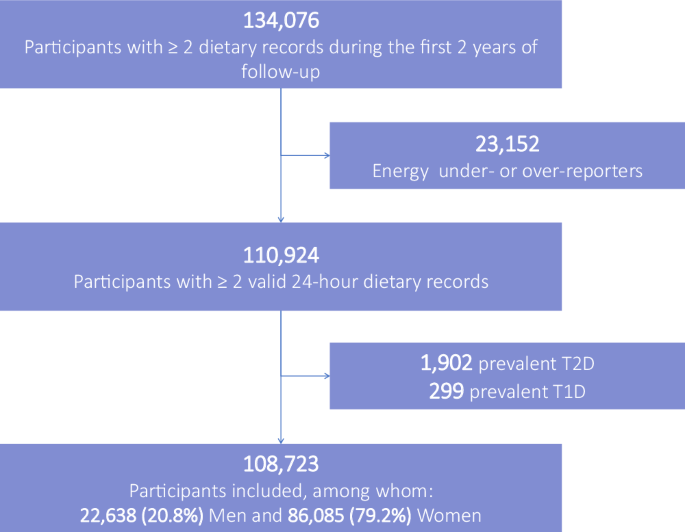

Upon registration and every 6 months, participants were asked to complete in sequences of three validated42,43,44 web-based 24-h dietary records (24HDRs). At each period, 24HDRs were randomly assigned to three non-consecutive days over 2 weeks (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day, to account for variability in the diet across the week and the seasons). At all times throughout their assigned dietary record period, participants had access to a dedicated interface on the study website to declare all foods and beverages consumed during 24 h: three main meals (breakfast, lunch, dinner) and any other eating occasion. Participants were asked to estimate portion sizes either by directly entering the weight consumed in the platform or by using validated photographs or usual containers51. The NutriNet-Santé food composition database (>3500 items) was used to estimate mean daily energy, alcohol, macro- and micro-nutrient intakes (including vitamins C and E)52. This database integrated all available data from the French national composition database (CIQUAL53), and further added information on additional components (e.g., food additive, trans fatty acids, etc.). These estimates included contributions from composite dishes using French recipes validated by food and nutrition professionals. The web-based questionnaires used in the study have been tested and validated against both in-person interviews by trained dietitians and urinary and blood markers42,43. In this analysis, we included participants having at least two 24-h dietary records during the first 2 years of follow-up. Participants who underreported their energy intake were excluded from the analyses and were identified using the method from Black, based on the original method developed by Goldberg et al.54,55. This method relies on the hypothesis that the maintenance of a stable body weight requires a balance between energy intake and expenditure. The equations developed by Black account for the reported dietary energy intake, basal metabolic rate (calculated using Schofield’s equations), sex, age, height, weight, number of dietary records, physical activity level (PAL), and intra/inter-individual variability56. As recommended by Black, the intra-individual coefficients of variation for BMR and PAL were fixed at 8.5% and 15%, respectively. In addition, a PAL of 1.55 was used to reflect a “light” physical activity, which is assumed to be attained by healthy, normally active individuals living a sedentary lifestyle. Finally, some individuals identified as under-reporters of energy intakes using Black’s method were not excluded if they also reported recent weight variations, adherence to weight-loss restrictive diets, or declared the consumptions entered in their dietary records as unusually low compared to their habitual diets. This ensured that flagged under-reporters have true incoherent reporting, and must be excluded. Although their exclusion may limit the generalisability of the findings, it was necessary to avoid important exposure classification bias.

In this study, 23,098 participants (corresponding to 17.2% of the subjects) were considered under-energy reporters and were excluded from the study. This proportion of under-reporters is common, for instance, in the nationally representative INCA 3 study conducted in 2016 by the French Food Safety Agency, 18% of adult participants were identified as under-reporters using the Black method35.

Several quality control operations were performed to account for over-reporting. Limitations in the online tool were set when participants reported the quantities of food consumed, aiming to alert them that the number they were about to enter was potentially an outlier, thereby encouraging double-checking and correction. Later on, during the data cleaning process, limitations were set per food category within one eating episode and per record for quantities; for instance, limitations for fruits were set for 3000 grams/day, 1500 grams/day for fish, 2000 grams/day for yoghurts, etc. These limitations are based on the 99th percentile of energy intake and are updated every 10,000 new dietary records added to the cohort if more than 10% of reported food items had outliers, then the full record was excluded. Otherwise, values were corrected to the maximum authorised values or standardised. In this study, 54 participants (corresponding to 0.04% of the subjects) were considered over-energy reporters and were excluded from the analyses.

Participants’ intakes of naturally occurring acetic and citric acids, nitrites, nitrates, and sulfites were quantified using multiple sources (see the Methods on Preservative Food Additive Intakes).

Preservative food additive intakes

Assessment of food additive intake in the NutriNet-santé cohort through brand-specific data of the 24HDRs has been previously described57. Each industrial food item consumed and reported in a specific dietary record was matched against three databases to assess the presence of any food additive: OQALI, a national database whose management has been entrusted to the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) and the French food safety authority (ANSES) to characterise the quality of the food supply (https://www.oqali.fr/); Open Food Facts, an open collaborative database containing millions of food products marketed worldwide (https://world.openfoodfacts.org/); and the Mintel Global New Products Database (GNPD), an online database of innovative food products in the world (https://www.mintel.com). In a second step, the dose of food additive contained in each food item was estimated based on (1) ad hoc laboratory assays quantifying additives in specific food items (n = 2677 food-additive pairs analysed), (2) doses in generic food categories provided by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), or (3) generic doses from the Codex General Standard for Food Additives (GSFA)58. Dynamic matching was applied, meaning that products were matched date-to-date: the date of consumption of each food or beverage declared by each participant was used to match the product to the closest composition data available, thus accounting for potential reformulations.

The 80 preservative food additives listed in the Codex General Standard for Food Additives database59 or UK Food Standard Agency60 were eligible for the present study. However, the occurrence of some of them was very low in the French/European markets, thus the proportion of consumers was null; their list is provided in the footnote to Tables 2 and 3. We decided to include as food additive preservatives both preservatives per se as defined by Regulation (EC) No 1333/20086 and antioxidant food additives, as both prevent the spoilage of food (food additive antioxidants preserving food via an antioxidant mode of action). In this paper, the term “preservative food additives” includes both “preservative non-antioxidant food additives” and “preservative antioxidant food additives”. Some preservative food additives possess additional key properties (e.g., some emulsifiers). All food additives with preservative properties are included in the present paper. We summed individual preservative food additives with similar chemical structures into the following groups: total sorbates (European codes E200, E202, E203), total benzoates (E210, E211, E212), total sulfites (E220, E221, E222, E223, E224, E225, E228), total nitrites (E249, E250), total nitrates (E251, E252), total acetates (E260, E261, E262, E263), total propionates (E280, E281, E282), total ascorbates (E300, E301, E302, E304), total tocopherols (E306, E307, E307b, E307c), total erythorbates (E315, E316), total butylates (E319, E320, E321), total citrates (E330, E332, E333), and total EDTA (E385, E386).

The strength of our methodology relies on the precise qualitative assessment of additive exposure, i.e., the presence/absence of a specific preservative food additive in the food consumed. This unique level of detail is permitted by the fact that commercial names/brands of industrial products consumed were collected and matched with Open Food Facts, OQALI, and GNPD databases, providing the ingredient list and thus, the presence of the specific food additive, at the time when the product was consumed. Thus, we only attribute a non-null dose of a specific additive to a given product declared by a participant if this specific product contains this specific additive. Then, the quantitative assessment of the doses of additives in the products that contain a specific additive is challenging since manufacturers are not compelled to declare this information on the packaging. Hence, the 3-step method was used to assess doses in our cohort. In all, in the framework of the ADDITIVES project, we performed 2677 quantified analyses, corresponding to a total of 61 food additives in 196 different (generic) food items. “Pairs” (i.e., a specific additive in a specific food vector) selected for laboratory assays corresponded to the most frequently consumed and most emblematic commercial food/beverage items for a given additive. Specifically, for preservative food additives, we had access to 1138 laboratory quantified analyses corresponding to 58 preservative food additives (E200, E202, E203, E210, E211, E212, E220, E221, E222, E223, E224, E225, E228, E234, E235, E239, E242, E249, E250, E251, E252, E260, E261, E262, E263, E280, E281, E282, E285, E290, E300, E301, E302, E304, E306, E307, E307b, E307c, E310, E315, E316, E319, E320, E321, E322, E325, E326, E330, E332, E333, E334, E338, E385, E386, E392, E472c, E942, E1105) in 128 (generic) food items (several commercial brands were tested per food item, e.g., in the case of milk chocolate, milk chocolate with nuts, creamy desserts, omega-3 enriched margarines, sausages, jams, chocolate mousse…). In addition to the assays carried out by certified laboratories, which were sent to us by the consumer association UFC Que Choisir, we contacted two companies (Mérieux & Eurofins) and the Direction Générale de la Consommation, de la Concurrence et de la Répression des Fraudes (DGCCRF) to carry out these assays. Only the additives listed in their catalogue could be measured.

If data were unavailable from this source, EFSA and GSFA doses were only applied if the specific food item contained the specific food additive in its ingredient list. We used 3122 preservative food additive data from EFSA (data available online in each EFSA Opinion + transmission of specific information by EFSA following an official Public Access to Document request PAD 2020/077), related to 46 preservative food additives present in 977 food categories. EFSA collects much information from manufacturers related to their specific commercial products, but for confidentiality reasons, only transfers information for generic food items or food groups (no brand-specific data). As regards GSFA, we used 5149 preservative food additive data concerning 42 preservative food additives coming from 226 food categories. As for EFSA, data from GSFA are not brand-specific but relate to generic food items or food categories (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Overall, quantitative dose data from ad hoc assays and from databases were similar in magnitude (e.g., for food additive potassium sorbate (E202) in the brand-specific pre-packed carrot salad that we selected: laboratory assay = 0.987 mg/100 g vs. 1 mg/100 g in the EFSA database for the corresponding generic food item), which was not surprising since EFSA doses for instance correspond to an average of laboratory assay data received by the Agency from EU member states, manufacturers and various contributors.

Food additive sulfites are present in many foods and drinks exempted from mandatory nutritional/ingredient declaration (e.g., wines or vinegar), making it sometimes impossible to determine which specific sulfite additive was used. Therefore, in this study, specific food additive codes (E220-E228) were used when the information was available on the packaging, i.e., for food items with mandatory ingredient declaration. The total sulfite variable accounts for all sulfite additives, i.e., both from foods and drinks with a mandatory ingredient list and from other food items with added sulfite (unspecified code). This strategy was established to avoid counting twice the same dose of sulfite (e.g., wine with declared ingredients).

In order to adjust for intake from non-additive sources of a given substance, whenever composition data were available:

Participants’ intake of naturally occurring acetic and citric acids was quantified using the Australian Food Composition Database61, which has been matched to the NutriNet-Santé food composition database for this specific study.

The methodology used to quantify intakes from non-food additive sources of nitrites and nitrates in foods and beverages has been previously described3,62,63. Briefly, food-originated nitrites and nitrates were determined by food category using EFSA’s concentration levels for natural sources and contamination from agricultural practices7. The publicly available data from the French official regional sanitary control of tap water was used to estimate intakes via water consumption by region of residence64, via a municipality-specific merging according to the NutriNet-Santé participants’ postal code, as well as a dynamic temporal merge according to the year of dietary records.

Participants’ intakes of naturally occurring and food additive sulfites were quantified using the corresponding EFSA Opinion7 and matching to the NutriNet-Santé database for this study.

Intakes of non-food additive dietary vitamins C and E were computed from the NutriNet-Santé food composition database52.

Type 2 diabetes ascertainment

A multi-source approach was used to detect incident type 2 diabetes cases. Throughout follow-up, participants could report any health-related events, medical treatments, and examinations via the health questionnaires every 6 months or, at any time, directly via the health interface of their profile. Besides, the NutriNet-Santé cohort was linked to the national health insurance system database to collect additional information regarding medical treatments and consultations, and to the French national mortality registry to identify the occurrence and cause of death. We did not perform ad hoc biochemical assessment. Participants were asked to declare major health events through the yearly health questionnaire, through a specific health check-up questionnaire every 6 months, or at any time through a specific interface on the study website. They were also asked to declare all currently taken medications and treatments via the check-up and yearly questionnaires. A search engine with an embedded exhaustive Vidal® drug database is used to facilitate medication data entry for the participants. Besides, our research team was the first in France to obtain authorisation by Decree in the Council of State (n°2013-175) to link data from our general population-based cohorts to medico-administrative databases of the National Health Insurance. Thus, data from the NutriNet-Santé cohort were linked yearly to these medico-administrative databases, providing detailed information about the reimbursement of medication and medical consultations. An incident type 2 diabetes case is detected when a participant has either reported the pathology at least twice or reported it once along with the use of a related medication.

All 1131 type 2 diabetes incident cases were primarily detected through the declaration by the participants of a type 2 diabetes diagnosed by a physician and/or diabetes medication use, in follow-up questionnaires. The questions were: “Have you been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (if yes, indicate the date of diagnosis)” and “Are you treated for type 2 diabetes?”. ATC codes considered for type 2 diabetes medication were A10AB01, A10AB03, A10AB04, A10AB05, A10AB06, A10AC01, A10AC03, A10AC04, A10AD01, A10AD03, A10AD04, A10AD05, A10AE01, A10AE02, A10AE03, A10AE04, A10AE05, A10AE30, A10BA02, A10BB01, A10BB03, A10BB04, A10BB06, A10BB07, A10BB09, A10BB12, A10BD02, A10BD03, A10BD05, A10BD07, A10BD08, A10BD10, A10BD15, A10BD16, A10BF01, A10BF02, A10BG02, A10BG03, A10BH01, A10BH02, A10BH03, A10BX02, A10BX04, A10BX07, A10BX09, A10BX10, A10BX11, A10BX12.

In addition to the abovementioned questions about the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or a medication report, two additional sources of confirmation were considered. First, linkage with the medico-administrative databases confirmed more than 80% of the cases surveyed (ICD-10 codes E11). Second, among participants who provided a blood sample at the clinical/biological examination, 85.3% of those with elevated fasting blood glucose (i.e., ≥1.26 g/L) had consistently reported a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or medication. However, elevated blood glucose without any declaration of type 2 diabetes diagnosis or treatment was not considered specific enough to classify the participant as a type 2 diabetes case.

Statistical analyses

Participants from the NutriNet-Santé cohort who completed at least two 24HDRs during their first 2 years of follow-up, those who were not under- or over-energy reporters, and who did not have any prevalent type 1 or 2 diabetes at enrollment were included in the analysis (flowchart of participants presented in Fig. 1). Baseline participants’ characteristics were described as mean (SD) for quantitative variables and n (%) for qualitative variables for the overall population and per baseline sex-specific tertiles of total preservative food additives. A correlation matrix was generated to visualise the Spearman correlations between intakes of individual food additives (Supplementary Fig. 1). For each studied additive or group of additives, participants were categorised into lower, medium, and higher consumers defined as sex-specific tertiles if the additive was consumed by at least 66% of participants, or non-consumers, and consumers separated by the sex-specific median otherwise (cut-offs provided in Supplementary Table 6). The relationship between preservative food additive intake coded as categorical a cumulative time-dependent exposure and the incidence of type 2 diabetes were investigated using multivariable proportional hazard cause-specific Cox models with age as the time scale to account for the competing mortality risk during the follow-up period. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated. Participants contributed person-time to the models from their age at enrollment in the cohort (which corresponds to the completion of the first set of 24HDRs) until their age at the date of type 2 diabetes ascertainment, type 1 diabetes diagnosis, death, last contact, or 31 December 2023, whichever occurred first. A counting process structure was used with cumulative time-dependent dietary variables updated every 2 years. Exposure during a specific period was calculated using a weighted average of the most recent 2-year period and prior periods, thereby using all available dietary record data. The time-to-event data structure was used with time-dependent dietary variables updated every 2 years. Exposure during one period was computed using a weighted average of the most recent 2-year period and prior periods. Each period contained averaged food additive intakes from the available dietary records within each 2-year period. The maximum number of 2-year periods was seven, to cover the maximum follow-up period of 14 years. A cumulative exponential decay weighting scheme was used to attribute lower weights to recent periods and higher weights to more ancient ones, given the fact that physio-pathological mechanisms underlying potential causal associations between additive intake and diabetes onset are expected to take several years (food additive intake consumed the month before diagnosis is less likely to have caused diabetes onset than more ancient usual exposure). Thus, for instance, intake during period 3 (years 5–6 of follow-up) = [intake during period 1 (years 1–2) + intake during period 2 (years 3–4) / 2 + intake during period 3 (years 5–6) / 4] / (1 + 1/2 + 1/4). The same methodology was applied to all dietary data. Cut-offs for food additives were updated for each follow-up period and are provided in Supplementary Table 1. For incident cases, dietary data collected during periods after type 2 diabetes diagnosis were not accounted for.

For incident cases, dietary data collected during periods after type 2 diabetes diagnosis were not accounted for. The principal model was adjusted for age (time-scale), sex, baseline BMI, height, physical activity, smoking status, number of smoked cigarettes in pack-years, educational level, family history of diabetes, number of dietary records completed, time-dependent daily intakes of energy without alcohol, alcohol, saturated fats, sodium, fibre, sugars, fruits and vegetables, dairy products, red and processed meats or heme iron (for nitrites and nitrates models only). Missing values for covariates were handled by a multiple imputation approach using additive regression, followed by bootstrapping, and predictive mean matching (n = 20 imputed dataset) as implemented in the Hmisc R package (version 5.1-0)65. Specifically, the imputation model included a comprehensive set of predictors deemed relevant to the missing covariates. Variables were incorporated to capture the underlying relationships and patterns. The choice of predictors (i.e., age, sex, family history of diabetes, physical activity, incident type 2 diabetes, education level, smoking status, BMI, energy intake, and alcohol intake) was guided by their known or hypothesised associations with the variables containing missing values. Missing values were imputed for the following variables: physical activity level (13.59% of missing values), BMI (2.76%), height (2.76%), smoking status (0.29%), number of smoked cigarettes in pack years (0.30%), education level (0.96%), and family history of diabetes (0.31%).

Moreover, whenever relevant, models were adjusted for the intake of the corresponding substance coming from naturally occurring sources. Associations between intakes from these natural sources and type 2 diabetes incidence were also tested. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using the Schoenfeld residual method (Supplementary Fig. 2) implemented in the survival R package (version 3.5-8)66. Restricted cubic splines with three knots covering each food additive distribution: 27.5th, 72.5th and 95th percentiles (Supplementary Fig. 3)67 were employed to investigate potential non-linear dose-response associations. When the log-linearity assumption was not rejected (p for non-linearity ≥0.05 in the Restricted Cubic Splines models), the p for linear trend was retained (obtained by coding the exposure as an ordinal categorical variable 1, 2, 3). When the assumption of log-linearity was not met (p for non-linearity <0.05), it was not adapted to calculate a p for linear trend; thus, the likelihood ratio overall p value was retained (obtained by coding the exposure as a non-ordinal categorical variable and calculating the likelihood ratio test between models with and without the studied food additive exposure variable). We have tested the associations between food preservative additive exposures and hip fracture (i.e., outcome with no expected causal relationship) as a “negative outcome control model”. We tested the proportion of the association between ultra-processed food68 intake and type 2 diabetes incidence that was mediated by food additive preservatives found associated with diabetes in this study, using the CMAverse R package (version 0.1.0)69 and the same adjustment variables as the main model. Sensitivity analyses were tested based on the main model: additional mutual adjustment for other preservative food additives intakes except the studied one (continuous, mg/d) (model 1); additional adjustment for the baseline weight proportion of ultra-processed food intake (model 2); additional adjustment for the diagnosis and/or treatment for at least one prevalent metabolic disorder (i.e. cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia or hypertension) (model 3); additional adjustment for time-dependent intakes of total emulsifier and total artificial sweetener food additives (continuous, mg/d) (model 4) (these two categories of food additives have been associated with type 2 diabetes risk in NutriNet-Santé); additional adjustment for baseline intake of vitamin C (continuous, mg) and vitamin E (continuous, mg) from dietary supplements (model 5); additional adjustment for trans fatty acids intake (continuous, mg) (model 6); adjustment for PCA-derived dietary patterns rather than individual food groups (continuous, see Method for deriving dietary patterns by principal component analysis and corresponding factor loadings for determination of dietary patterns) (model 7); additional adjustment for time-dependent intakes of polyunsaturated fatty acids (continuous, g/d) and heme iron (continuous, mg/d) (model 8) (for preservative antioxidant food additives only, since antioxidant may counteract polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation by heme iron); follow-up starting at the end of the first 2-year period (model 9); without exclusion of under-reporters (model 10); use of marginal structural models with stabilised and truncated at 99th percentile inverse probability of treatment weighting as recommended by Young et al.70 (model 11); relaxing log-linearity assumption on covariates adding splines with the R package splines (version 4.3.3) (model 12). All statistical tests were two-sided, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with R version 4.3.3, except for the restricted cubic spline method, which was implemented with SAS version 9.467.

Method for deriving dietary patterns by principal component analysis and corresponding factor loadings

Dietary patterns were identified based on 20 food categories, using a principal component analysis conducted with the R package FactoMineR (version 2.8)71. The principal component analysis creates linear combinations (called principal components) of the initial set of variables, with the aim to group those that are correlated while explaining as much variation from the dataset as possible. We used the scree plot generated by the principal component analysis to select the retained principal components (with eigenvalues ≥ 2). For easier interpretation, we used the R “varimax” option to rotate the principal components orthogonally and maximise the independence of the retained principal components. The variable coefficients derived from the selected principal components are called factor loadings. A positive factor loading indicates a positive contribution of the variable to the principal component, whereas a negative factor loading indicates a negative contribution. For the interpretation of the two principal components selected, we considered the variables contributing the most to the component, i.e., with loading coefficients under −0.25 or over 0.25. We then label the principal components descriptively, based on the most contributing variables. Finally, we calculated an adherence score for each principal component and for each participant, using the food categories factor loadings to weigh the sum of all observed intakes. Thus, the adherence score measures a participant’s diet conformity to the identified dietary pattern intake pattern. In the analyses of dietary patterns, we identified a healthy pattern (explaining 10.88% of the variance), which was characterised by higher intakes of fish and seafood, fruits, unsweetened soft drinks, vegetables, and wholegrains, along with lower intakes of sweetened soft drinks. In contrast, we identified a Western pattern (explaining 7.9% of the variance), which was characterised by higher intakes of fat and sauces, potatoes and tubers, and soups and broths.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Dining and Cooking