Although I’ve had success with both homemade yeast breads and sourdough in the past, lately (now in the summer in the southern hemisphere) I’ve been disappointed with a few bakes, whether in terms of crumb structure or oven spring. Since I follow some international baking pages, I started wondering whether flour might be playing a more significant role than I had assumed — especially because, in my recent tests with hydration above 70%, I found local (Brazilian) flours somewhat annoying to work with. That could also be partly due to the fact that I live on the coast, where humidity is consistently high in the summer.

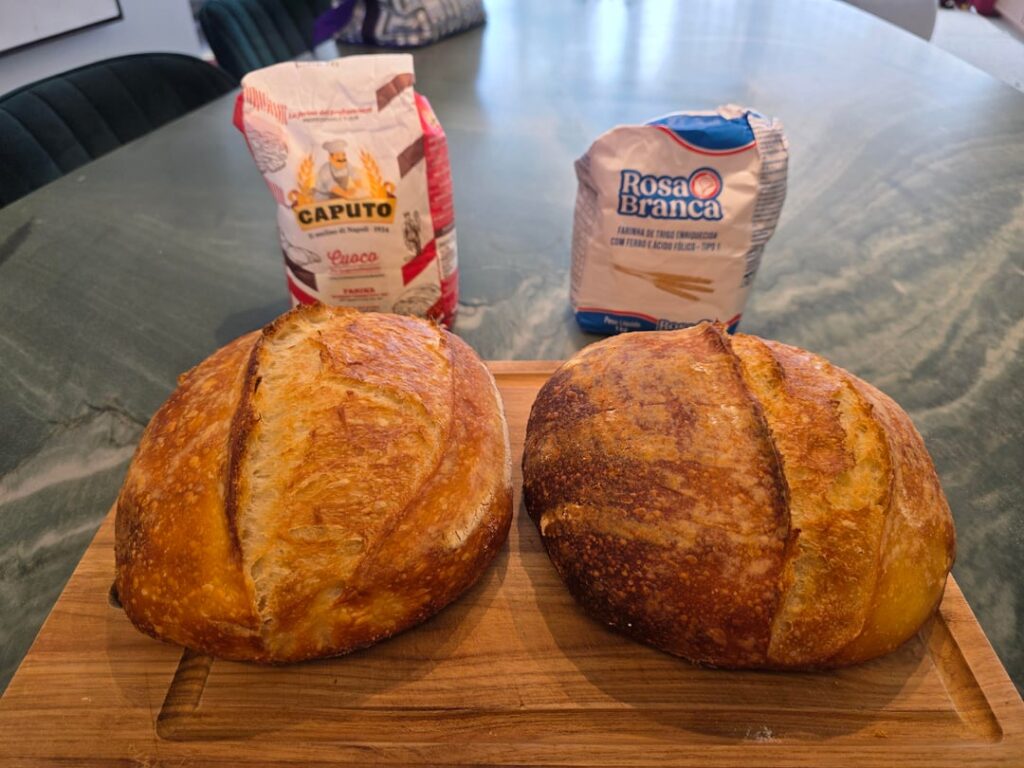

With that in mind, I decided to run a small test using Italian Caputo Cuoco flour and Brazilian Rosa Branca flour, both labeled as having 13% protein. In this particular case, we’re talking about a price difference of more than US$ 4 per kilo.

I chose to make a “commercial yeast” bread, using instant dry yeast, because I also wanted to evaluate flavor and avoid masking the flour with the more acidic, lactic notes of sourdough (and, honestly, because I didn’t have that much time for the test). I used a recipe with 70% hydration, 2% salt, and 1% instant dry yeast. I followed exactly the same steps with both doughs, in the same environment and at nearly the same time, to minimize confounding variables.

The process, in short, was: mix, fermentolyse (~40 min), slap-and-fold, rest (30 min), coil folds, bulk fermentation (~4 h, with ~50% volume increase), shaping, cold retard at 2 °C for about 15 h, and baking at 230 °C in a cast iron pot for 25 minutes, followed by another 25 minutes uncovered for browning. The only difference was the banneton shape: round for the Rosa Branca loaf and oval for the Caputo Cuoco.

Verdict: at 70% hydration, under my temperature and relative humidity conditions, the Rosa Branca flour already started to feel a bit more difficult to handle. It was still workable, but the Caputo clearly developed gluten faster, stopped sticking sooner, and offered more resistance during folding. In all other stages up to baking, both doughs behaved quite similarly.

In the final result, in my opinion, the Caputo loaf looked more visually appealing. It seemed to hold the banneton shape better and had a more pronounced ear. That said, the loaf made with Rosa Branca baked well and did form an ear, albeit a more modest one — which could also be related to my scoring.

The crumb surprised me. I found them very similar, except for color: the bread made with Rosa Branca flour was noticeably more yellow, possibly due to iron and folic acid fortification, which is mandatory in Brazil but not in many other countries.

Flavor-wise, they were also quite close. I did a blind tasting with my boyfriend, and he described the crumb of the Rosa Branca loaf as slightly more “bitter,” though not unpleasant. I suspect this could be related to a mild metallic note from the flour enrichment — but that’s just speculation on my part.

Overall, I’d say that if you really care about the visual appearance of the loaf and the crumb color, opting for imported flour can be a shortcut to more consistent results. I have no doubt that more experienced bakers can achieve excellent outcomes with local flours; I’m speaking more from the perspective of a newbie. In absolute terms, I don’t think the extra cost of more than US$ 4 per kilo is justified for this type of 70% hydration recipe, since the final results are quite similar. In other applications, of course, the differences may be more pronounced.

One important contextual note: in Brazil, it’s often very hard to find technical information about flour, such as W index, P/L ratio, ash content, or even clear details about the milling process. Many flours are sold with little more than protein percentage on the label. I’m posting this partly to highlight that when we see recipes online from Europe or the US and can’t replicate the same results, it’s not always a matter of technique — in some countries, flour quality, milling standards, and available specifications are simply very different.

I want to emphasize that this test wasn’t replicated, so it has no strong scientific validity. It’s just a personal reference, within my own skills (and limitations) and the equipment I have. Still, I thought it might be interesting to share. I’ll attach some photos of the results and plan to test other flours soon.

by Jhfallerm

9 Comments

Fun comparison! I recently read a book on sourdough (embarrassingly, the title and author have already left my brain) and the author claimed that in her experience, different flours will absorb different amounts of water even when they have supposedly identical protein content. I’d be interested in another side by side test comparing ~65% hydration with your stickier flour vs 70% hydration with the less sticky one. Maybe even a three-way comparison repeating the 70% hydration level with your sticky flour!

Aqui no Brasil não tem muitas informações de W e P/L pq não são testes padronizados aqui. A São poucos os moinhos que fazem esses testes e até onde eu saiba praticamente nenhum dos moinhos que tem nos supermercados fazem.

Dito isso, não acho que seu problema seja a farinha, os dois pães estão subfermentados e faltou um pouco do desenvolvimento do glúten. Acredito que se vc resolver essas coisas, mesmo usando farinha nacional, vai ter bons resultados.

Não sei a porcentagem de fermento que vc está usando, mas aqui na minha cidade ta super quente e úmido, quando o tempo está assim costumo reduzir a % de fermento na massa

Is the Italian Flour actually from wheat grown in Italy? IIRC Italy gets a lot of wheat (especially Durham Wheat, mostly for pasta) from the US. So a lot of “Made in Italy” pasta was made from US wheat.

I just want to point out that I am aware that the loafs might not be optimal in terms of bulk fermentation times, yeast to flour ration, gluten development etc. Nonetheless I think the comparison still holds – how forgiving is your flour given your limitations as a baker? Perfect technique could lead to perfect loaves with both flours, but I am not gonna be the one able to test that hypothesis xD

This was super educational and really interesting to read, thank you for taking the time!

Congratulations! This is very well done. Precise analytical specifications for wheat flours are typically only provided to bilk load customers. Anything provided for a retail product is not a lot analysis, and rather a typical specification expectation for that product code. You are so correct about milling practices. What of course also comes in to play is wheat sourcing and availability. I worked many years for a flour milling company in Canada with 7 different flour mills in Canada, 19 in the USA, and several more in UK and Caribbean. Even a mill with a similar wheat grist can produce different results. The number of roll stands, sifters, settings, etc. all play a roll.

In the EU the wheat grown is mostly soft wheat, and typically produces more starch damaged flour. They are likely blending with US, Canadian, and or Ukrainian hard wheat. In Europe they measure the protein on a dry basis. Flour has on average 14% moisture. So what this means is that a 13% protein European flour would the same value number as 11.2% protein in North America. In Canada it is not unusual to obtain 54 ash flour with 14% protein. This would be like T55 in Europe with 16.3% protein. The creamy yellow crumb you see has to do with the age and oxygen exposure to the flour. This alters the natural creamy yellow pigment to become “bleached”, and more white in appearance. Adding a small amount of enzyme active soy flour, and aging for 24 hours, can provide some of this effect too. Many large pan bread bakeries are doing this today, in favour of bleaching with peroxides. The enrichment does not add any colour, nor discernible flavour. Any bitterness make come from bran particles, or if the flour is extremely old, possibly rancidity of the fat content.

It all comes down to protein is not just protein. There are measurable performance and predictability differences. You can learn more about the analytical instruments for your interest on http://www.bakerpedia.com

Amigo, procure a farinha Globo Superiore w300. É a melhor farinha nacional que já encontrei. Na minha região (SC) eu nunca encontrei em mercados, mas comprava pela amazon relativamente barato (5 e pouco o kg).

You should try the special Caputo flour!

Ciao

This confirms my suspicion that protein percentages on labels are total lies.