From her dining table overlooking the sea, with a vegetable patch full of tomatoes and decades of research behind her, Associate Professor Antigone Kouris-Blazos practises what she teaches.

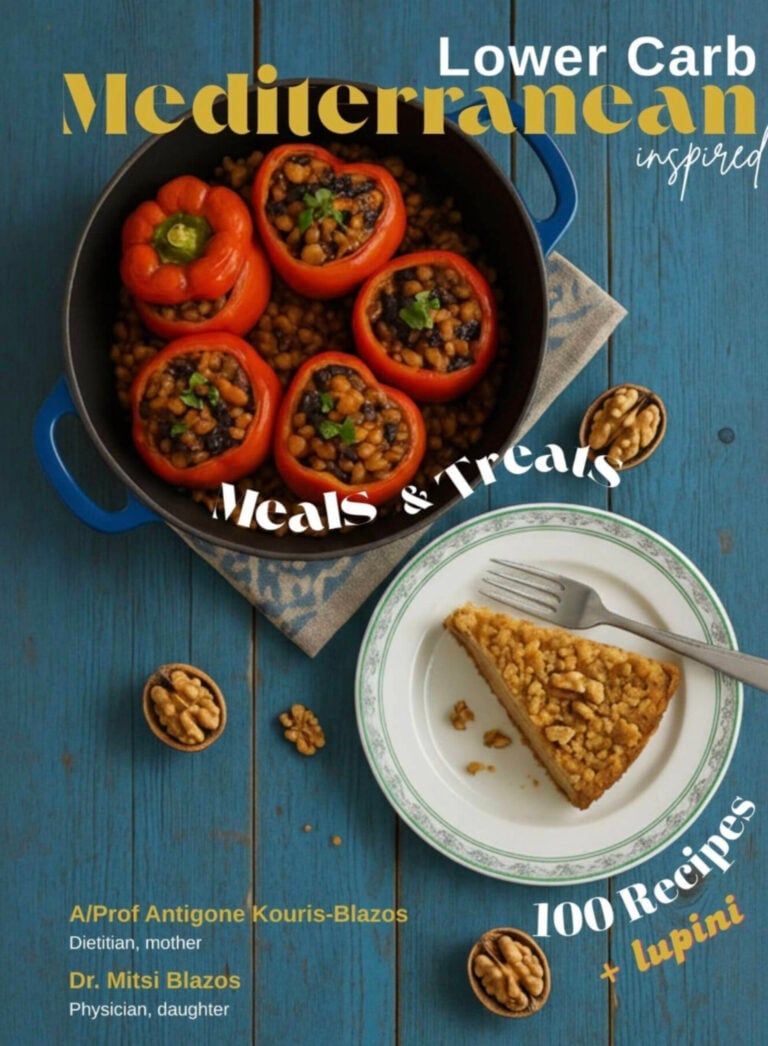

Together with her physician daughter, Dr Mitsi Blazos, she has distilled a lifetime of nutritional science into their newly released cookbook, Lower Carb Mediterranean Inspired Meals and Treats, a practical guide born from clinical experience, and the everyday questions of patients seeking a healthier way to eat without sacrificing flavour or tradition.

Kouris-Blazos, an Accredited Practicing Dietitian, says the book grew from years of requests for healthy lower carb Mediterranean recipes.

As a physician and trainee endocrinologist, Dr Mitsi Blazos has witnessed first-hand the impact of nutrition on health, seeing significant patient remission from type 2 diabetes through a lower-carb version of the Mediterranean diet. Meanwhile, her mother’s landmark PhD was the first to study the Mediterranean Diet Pattern and its contribution to the longevity of Australians born in Greece. She has also seen great results with lower carb Mediterranean diet in patients wanting to better manage their weight or blood glucose.

“My patients kept asking for recipes.” Kouris-Blazos says. “Over 20 years I was writing recipes on bits of paper, printing them here and there. Eventually I realised I needed to compile them and make them easy to access.”

Many patients also didn’t fully understand what the Mediterranean diet looked like in practice.

“The book gives clear guidance,” she explains. “How to cook in tomato-based sauces, how often to eat greens and legumes, and how to build meals around plant foods rather than meat.”

Australians, she notes, eat very few legumes, which is one of the foods most strongly linked to longevity.

“We wanted to teach those skills,” she says. “And we wanted desserts too, because people with diabetes still crave sweet foods. We wanted treats that feel indulgent but support health.”

Many of the dishes are adapted from family recipes the two grew up with.

It was her own mother’s cooking that first sparked Kouris-Blazos’ interest in nutrition. “My mother’s parents came from Constantinople, and she picked up a lot of flavours and recipes from there. Even as a young girl, I felt that there was something special about Greek cooking, because it seemed so healthy.”

A childhood allergic reaction to strawberries made her even more curious.

“I remember thinking, how powerful is food? How can something so pure cause such a reaction? That’s what got me interested in the chemistry of nutrition.”

Her daughter grew up surrounded by the same influence, with two Greek grandmothers who made the kitchen the heart of the home.

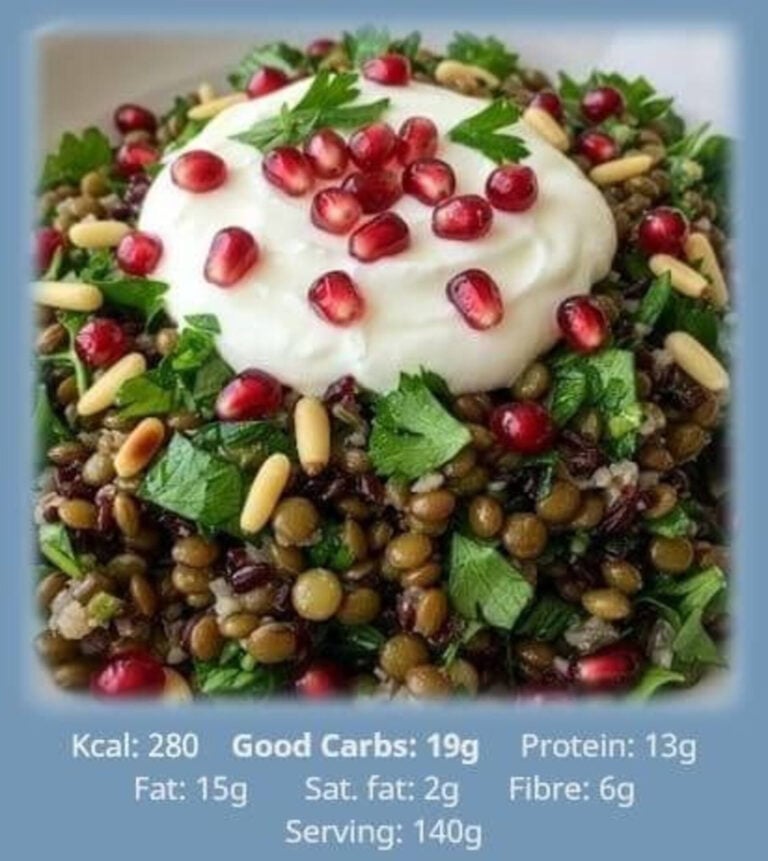

Greek Grain & Lentil Salad

Greek Grain & Lentil Salad

Researching longevity

Kouris-Blazos has been an Associate Professor in the Department of Dietetics and Human Nutrition at La Trobe University since 2011.

Her academic journey began in the 1990s, when her honours supervisor, Professor Mark Wahlqvist at Monash University, noticed that Greek-born Australians appeared to live longer than Australian-born citizens.

“He suggested I investigate why. I wasn’t planning on doing a PhD, but the question fascinated me.”

The study followed more than 800 participants across multiple countries, including Greeks in Melbourne and Greece, Anglo-Australians, Japanese in Japan and Swedes in Sweden. After several years, mortality data revealed that Greeks in Melbourne had substantially lower death rates when they adhered to a Mediterranean dietary pattern.

Importantly, the research did not measure specific cuisines but rather the balance of plant and animal foods. Higher scores were linked to greater intake of legumes, olive oil, nuts, whole grains and vegetables, and lower intake of animal products.

One striking finding emerged when a student analysed which foods most strongly predicted longevity. Legumes ranked highest.

“We expected olive oil or fish,” she says. “So it surprised us that legumes were the standout food group.”

Greek Chickpea &Tomato Stew

Greek Chickpea &Tomato Stew

Greek migrant paradox

Another unexpected discovery was what researchers dubbed the “Greek migrant paradox”.

Despite living longer, many elderly Greek Australians were overweight and had diabetes, high cholesterol or high blood pressure.

“Our theory was that their diets were so rich in plant foods and antioxidants that they helped offset some of those risks,” she explains.

“Many also had incredible gardens and grew their own vegetables which provided this rich source of antioxidants.”

Migration patterns may also have played a role. Early prosperity in Australia led to more celebratory eating, more red meat, butter, cheese and sweets than in their homeland contributing to obesity and diabetes. But later in life many returned to traditional eating habits, which may have helped protect their health.

“It shows it’s never too late to improve your diet,” she says.

Lupin: The king of legumes

Along the way, Kouris-Blazos discovered a superfood. Lupin, a legume consumed on many Greek islands, and especially Crete where her family comes from.

It contains roughly twice the protein of other legumes (around 40 per cent, comparable to meat), three times the fibre, and is dramatically lower in carbohydrates and glycaemic index than other legumes. It also has more iron than lentils, more antioxidants than berries and more potassium than bananas, along with high levels of magnesium. Lupin has been shown in several studies to be diabetes friendly and to reduce hunger.

Lupin features in 21 recipes in their cookbook and is also the key ingredient in Kouris-Blazos’s low carb Skinnybik biscuit brand created with the help of her engineer husband Chris Blazos who took care of production and packaging. Skinnybik was launched in 2010 after a patient challenged her to create a biscuit she could safely eat. The biscuits were clinically trialled in 2020 with hospital patients with diabetes and were found to improve blood glucose levels and reduce hunger.

Baked Fish Fillets in Pesto & Tomato Salsa

Baked Fish Fillets in Pesto & Tomato Salsa

More than food

From all her research, Kouris-Blazos knows that longevity is not just about what we eat. Walking or dancing after a large meal, as you still see at Greek festivals, taking siestas, and maintaining strong social connections all play a role.

In her vegetable garden by the sea, she harvests tomatoes, one of the most important ingredients in the Mediterranean diet. The tomato salsa used in so many dishes puréed with onions, celery, carrots, herbs and spices is something she recommends people use at least twice a week. “When you cook tomatoes that way, the levels of antioxidants actually increase, and they’re absorbed even better when cooked in olive oil with herbs and garlic.”

Warning the next generation

Are younger Greek Australians following in the footsteps of that long-lived first generation? Not quite. Kouris-Blazos has noticed diets heavy in red meat, chicken, barbecued food, ultra-processed products, refined grains, sugary drinks, fast food and alcohol.

It is precisely for this reason that she hopes the cookbook will find its way into the hands of younger readers, to help them move away from ultra-processed convenience food and back toward Mediterranean-style eating, lower in refined carbohydrates and higher in vegetables and legumes.

“We need to stop the diabetes tsunami before it starts,” she says.

And it is quite simple to turn your diet around, she adds. She suggests starting with two vegetarian meals a week based on legumes such as fakes, fasolada or revithia; two dishes a week cooked in tomato salsa; dark leafy greens at least twice a week — horta, silverbeet, Asian greens, spinach; and choosing cold or reheated rice, pasta or potatoes where possible, since reheating increases resistant starch which in turn reduces glucose and insulin spikes.

Growing up, Kouris-Blazos ate legumes constantly. “I think the biggest change in the younger generation is that they’ve stopped cooking legumes, and they’ve stopped cooking with tomato. They do stir-fries instead, which are quick and easy, but my concern is the sauces. Hoisin, soy, fish sauce: they often contain added sugar, salt and MSG.

Dining and Cooking