The harmful nature of plastic debris in the marine environment is well documented (Derraik, 2002; Duis and Coors, 2016; Koelmans et al., 2014); the ingestion of pieces of plastic ranging from <5 mm (microplastic) to >25 mm (macroplastic), can cause physical obstructions and decreases in fitness levels to all marine trophic levels (Lee et al., 2015). In addition microplastics can be translocated into the tissue of marine species, releasing chemical contaminants which may accumulate throughout the food chain (Koelmans, 2015; Avio et al., 2015). Due to its semi-enclosed nature and heavy coastal pressures, the Mediterranean Sea is exposed to high densities of marine debris. It is estimated that between 1000 and 3000 tons of plastic is floating in the Mediterranean Sea (Cózar et al., 2015) yet despite this, a recent report by the United Nations Environment Programme/Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP/MAP) states that Mediterranean countries have not yet drawn up their marine litter monitoring programs in a coherent and harmonized manner (UNEP/MAP, 2016).

For European waters in the Mediterranean, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD), with the aim of assessing the progress towards the achievement of Good Environmental Status (GES) in European waters, requires member states to ensure that “The amount of litter and micro-litter ingested by marine animals is at a level that does not adversely affect the health of the species concerned” (EU 2017/848). Member states are required to establish threshold values for the amount and composition of litter ingested by marine animals and long-term monitoring of plastic ingestion trends is essential for defining these threshold values needed to achieve GES (Galgani et al., 2014). The proposed protocols that are used for the MSFD to quantify the level of litter being ingested are largely based on the working recommendations from the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR). Assessments of marine plastic levels are most commonly done by examining stomach contents of the plastic trend bioindicator the Northern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis (Linnaeus, 1761)) (van Franeker et al., 2011), however, its distribution does not extend to the Mediterranean Sea. In recognition of this, an MSFD technical subgroup (MSFD TSG-ML) formed for the further development of the Marine litter descriptor used to achieve GES, suggests that the Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758)) should be used as target species for monitoring macroplastic ingestion trends in the Mediterranean Sea (Camedda et al., 2014; Matiddi et al., 2017, 2011), and recommends the development of a general protocol for measuring trends and regional differences in micro (<5 mm)/meso (5–25 mm) plastic ingestion by fish. The guidelines fail to specify however, which species should be used (Galgani et al., 2013). Differences in fish sizes, life histories, and distributions, mean that to achieve effective comparisons of environmental status at sites throughout the Mediterranean Sea, the species of fish used for analyses should be standardized. A lack of a standardized protocol throughout the Mediterranean basin means measurements of plastic ingestion levels are often sparse and disparate (Bonanno and Orlando-Bonaca, 2018).

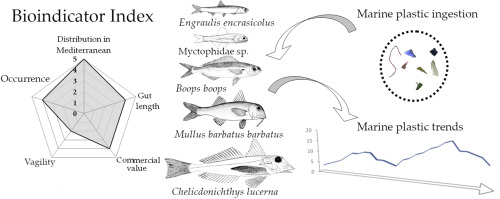

Multiple traits influence how effective a species is as a bioindicator for plastic ingestion trends e.g. size, life history, distribution, vagility, habitat type, conservation status, and socio-economic importance (Carignan and Villard, 2002). Depending on the particular research objective (e.g. measurement of pollution over a large area, investigation of the cumulative impacts of a stressor over a long period, or the production of spatial/temporal environmental status snapshots), certain species are more appropriate than others. With regards to the MSFD, monitoring should be done on a regular basis within member states territorial waters, to assess whether GES has been achieved in European waters. The target species should therefore be easily found at sampling sites, be resident to the member states territorial waters, and have a relative short digestion period to ensure that the ingestion of the target pressure (i.e. plastic) occurs in the vicinity of the habitat being investigated. In addition, the use of commercially important species could enable the estimation of the potential transfer of plastics, and their associated contaminants, from seafood to humans (Fossi et al., 2018). Building on the foundation of several recent works that have compiled lists of Mediterranean bioindicator species and defined the selection criteria for choosing suitable organisms (Fossi et al., 2018; UNEP/MAP, 2018, 2016), this study aims to assess the effectiveness of selected fish species as marine plastic ingestion bioindicators by formulating an index (Bioindicator Index) to identify the most suitable species, as it is expected that the suitability of individual fish species varies greatly. The results will aide in the standardization of national and international marine plastic monitoring protocols throughout the Mediterranean Sea.