Summary

The three foods given to humankind by Roman gods continue to form the basis of the Mediterranean diet, with olive oil, bread, and wine being key components. Archaeologists recently gathered online to discuss the history of the diet and celebrate its eleventh anniversary on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list, highlighting the importance of agriculture and the contributions of various populations to the diet over time.

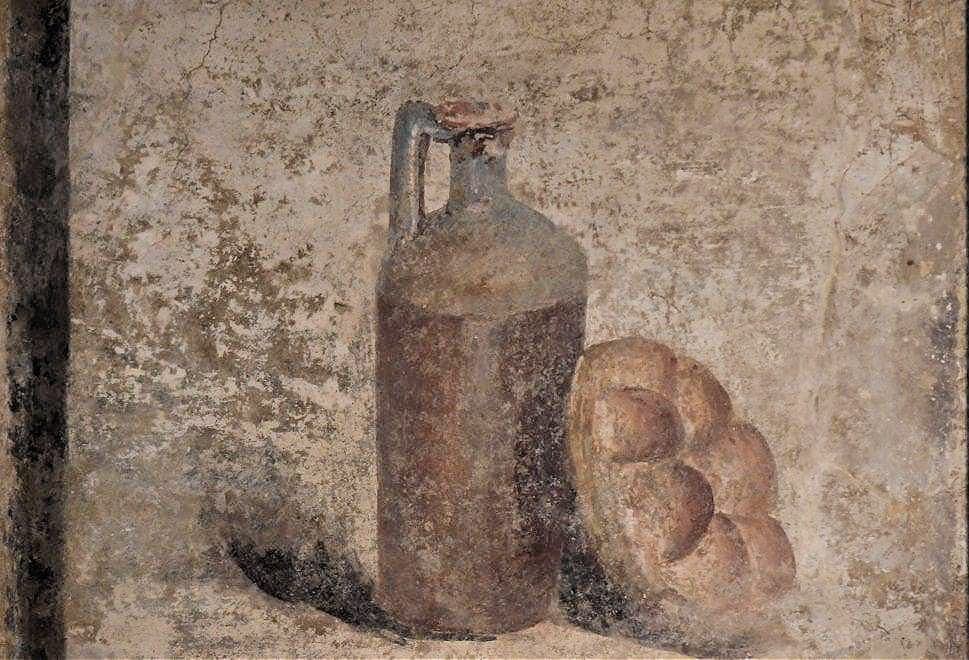

According to Roman mythology, there were three foods that the gods gave to humankind.

Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, gave an olive tree. Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, gifted wheat. Dionysus gave Romans the vine.

While the Mediterranean diet is a combination of factors such as history and necessity, we also have to consider the great passion for food that the civilizations of the past left us.- Elisabetta Moro, co-director, Mediterranean Diet Virtual Museum

From these three gifts came foods that continue to constitute three pillars of the Mediterranean diet: olive oil, bread and wine.

Archaeologists recently gathered online to discuss the history of the diet and celebrate the eleventh anniversary of its inclusion on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

See Also:Pottery Shards in Croatia Reveal Roman Olive Oil and Military History

Among the guests at the seminar was the director of the Naples Archeological Museum, Paolo Giulierini, who led the audience on a journey through ancient sources.

“In the countries of the so-called ‘Mezzaluna fertile’ – mainly the Mesopotamia region, then neighboring countries such as Egypt and the Greek colonies – these three crops have always represented a source of wealth and sustenance,” Giulierini said. “Somehow, they were the ‘first nucleus’ of what we now call the Mediterranean diet.”

“Through the centuries, this nucleus has then been enriched thanks to the contributions from various populations in the Mediterranean area and beyond,” he added. “For example, we have known foods such as rice, tomatoes and some citrus fruits since the Middle Ages, not before.”

While further clues to unravel the past of the Mediterranean diet can come from the observation of ancient objects and paintings, Giulierini warned against some common misinterpretations.

“The everyday life dimension was rarely represented in the artistic works that have come down to the present day, which often had a celebratory or metaphorical meaning,” he said.

Photo: Mann Museum

Photo: Mann Museum

“Frescoes with banquets laden with exotic fruits, sweets or game were the expression of wealthy elites,” Giulierini added. “They did not represent the lifestyle of largest sections of the population, whose diet was determined more by the phases of agriculture than by free choice.”

“Objects for the transformation or conservation of food found in some Pompei villas can tell us a lot about the living standards of the wealthiest families; nothing about those of the masses,” he continued.

“That said, we know that in the Roman world agriculture was the basis for nutrition and food supply, and that fish breeding was beginning to spread,” Giulierini concluded. “Cattle was essential for agriculture, and animals were needed alive: the consumption of meat was, then, limited to a few exceptional occasions.”

See Also:Oldest Known Bottle of Olive Oil on Display in Naples Museum

Giulierini’s full report is available in the online gallery of educational and scientific contributions of the Mediterranean Diet Virtual Museum, the first digital museum in the world entirely dedicated to the Mediterranean diet.

The museum was created by MedEatResearch of the University Suor Orsola Benincasa, an Italian academic research center in Naples specifically dedicated to the Mediterranean diet.

“Our goal is to enlighten the cultural, economic, anthropological, gastronomic, medical, educational and ecological aspects of the Mediterranean diet,” said Marino Niola, an anthropologist and one of the museum’s directors.

“To achieve this, the museum will present our ethnographic research work and our studies on longevity through public activities such as seminars and conferences, and also by making available videos and ‘living testimonies’ of local producers, artists, scientists and citizens who recall the peasant society of the past,” he added.

Co-director Elisabetta Moro added: “While the Mediterranean diet is a combination of factors such as history and necessity, we also have to consider the great passion for food that the civilizations of the past left us.”

“Over the centuries, this passion has become a distinctive feature of our society,” she concluded. “Now the challenge is to preserve it and to enhance it through a food educational path involving society at large and, above all, young generations.”