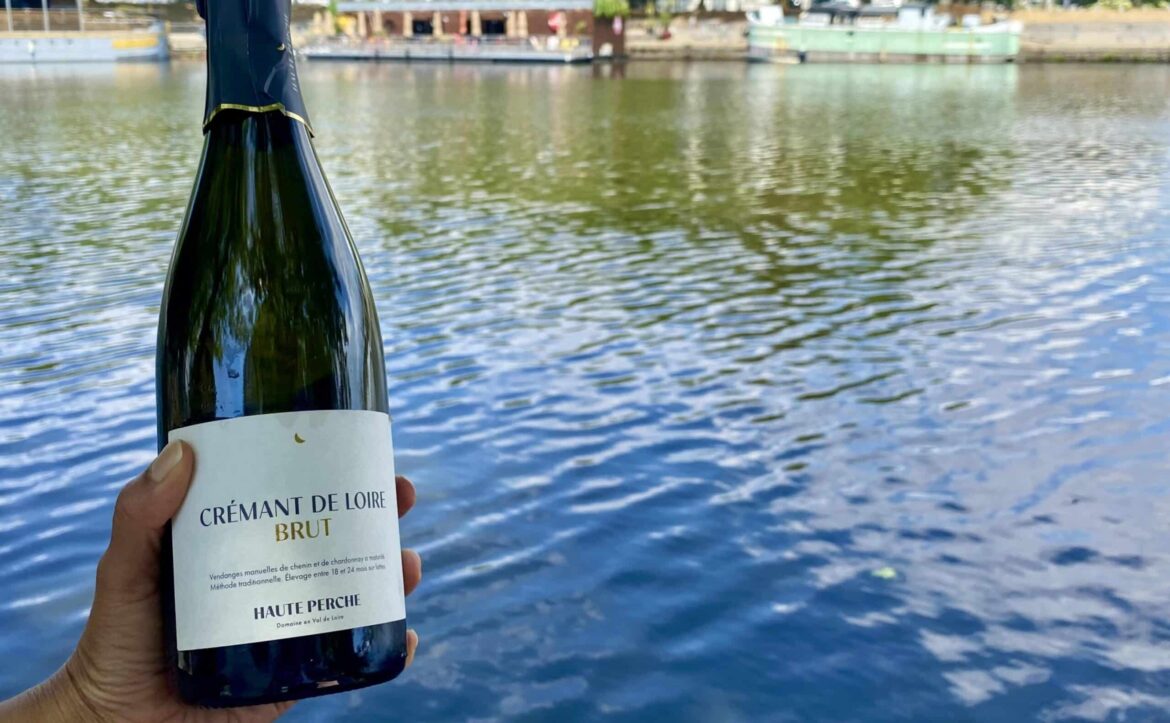

Enjoying Cremant de Loire along the River Loire.

Enjoying Cremant de Loire along the River Loire.

The following received via email from Simon Shear, a writer and content strategist specialising in financial services, currently based in London

My low-cost flight dipped into western France, the evening glittering, as it tends to on these long globally-warmed European summer days. The sun glinted off the water snaking into the Atlantic. It was the Loire. We were flying into chenin country.

I would be in Nantes for a long weekend, a short train ride from Angers, gateway to Anjou. From there, Savennières and its venerated whites. You could journey to Saumur if you were feeling ambitious.

I was feeling ambitious. I’d read up on soil and climate. I’d calibrated my palate with a glass of Ken Forrester. On the plane, I’d listened to a long podcast interview with Nicolas Joly, an invigorating mixture of quackery and wisdom.

In my imagination, I’d stroll into a prestigious domaine, identify myself as South African, and be whisked into the VIP section for Citizens of the Commonwealth of Chenin.

Until I remembered that Sunday in France is a write-off. And the Monday after that turned out to be Bastille Day, an embarrassingly Anglocentric oversight considering that the day is known as 14 Juillet in France. It’s like forgetting when Americans celebrate the Fourth of July.

In practice, we had one rushed afternoon to visit an estate or two. Still, I wanted to see chenin in its natural habitat and hopefully get a sense of how it differs from the stuff back home.

We duly arrived for our scheduled tour at a smallish winery in Anjou noir, named for its dark schist soils, distinct from the part of Anjou in which lighter-coloured limestone predominates. The difference is more than surface deep, affecting acidity, structure, minerality. On the actual influence of soil on wine, I defer to the experts, but that did not stop me pronouncing a distinct mineral note as I tasted. It’s a fun thing to say, impossible to argue with, and plausibly true.

The entry level white, at just ten euros a bottle, was excellent value. But it seemed at the time like an impossible bargain. Partly because I didn’t do the maths and partly because arrived from London, which warps one’s sense of what’s reasonable. Ten euros is currently about R210, so hardly bargain basement by South African terms.

But it wasn’t just a calculation of price per ml. This was the entry-level everyday wine, but it tasted prestigious. Though simple and with some soft fruit, it was relatively lean, transparent and, yes, mineral. A flavour profile I suspect many of us associate with the more cerebral type of premium, or at least boutique, winemaking.

And while I was at a boutique winery, my sense was that I was tasting Anjou, at least one straightforward rendering of it. How straightforward was made apparent when the estate’s excellent mid-range chenin was served.

Looking back, I realise that I was already thinking about wine in a different way. Not ‘what kinds of wines do they make in this place’, or ‘isn’t it interesting how the stuff in this glass is the product of grape selection and winemaking technique and climate and etc’ but rather: ‘what does Anjou taste like here compared to over there’. Not ‘what is this place suitable for’ but ‘how does this winemaker express this place in that bottling’. In other words, I was thinking in terms of terroir.

Now this could be a distinction without difference, and to winemakers and pros the observation will be painfully rudimentary. But I wonder to how many ordinary consumers in South Africa (or outside of Europe more broadly) this way of tasting comes naturally?

It’s not like I was unfamiliar with the concept of terroir or that I haven’t heard countless winemakers talk explicitly in those terms: ‘I want my wines to be an expression of X’.

Nor did I make a conscious effort to shift my perspective. It’s just that the small, subtle, interlocking and accessible appellations structure a kind of thinking, almost by default. (And give young producers something to rebel against, as evidenced by the preponderance of Vin de France designations at hip natural wine shops.)

In a post about (to briefly gloss past it in these pages) this year’s Swartland Revolution event, Victoria Mason quotes Adi Badenhorst on the profound sense of place among Swartland producers, “not just a physical but a spiritual connection”.

As a cortado-sipping suburbanite who barely remembers to water my houseplants, I don’t pretend to know what that really means. But, true to stereotype, it took a Ryanair flight and a summer weekend in an under-the-radar European city to get some sense of what it is not simply to see land as a vehicle to produce wine, but wine as a means of conveying a sense of place.

Dining and Cooking