QuickTake:

Lookout caught up with the respected food writer, whose recipes and watercolor illustrations graced Pacific Northwest newspapers for decades. Her focus now is on landscape art, but she left a lasting impact on Oregon’s food writing culture.

Many of our readers remember perusing The Register-Guard’s food pages in the 1990s and 2000s. For those readers, the name Jan Roberts-Dominquez likely brings back memories of mouthwatering recipes, beautiful watercolor illustrations and thoughtful stories that connected food to family and community.

After decades of writing for newspapers across the Pacific Northwest, Roberts-Dominquez is now focused on her art, but her influence on Oregon’s food writing landscape remains significant.

Roberts-Dominguez grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, and developed an interest in food during what she calls “a real food explosion” in the region. Alice Waters, who basically single-handedly launched the farm-to-table movement, opened Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, in 1971, and Roberts-Dominguez started paying attention to that scene in 1973.

“San Francisco was alive with food,” Roberts-Dominguez said. “We spent a lot of our summertime and weekends up in Sonoma Valley with relatives who would drive around to the wineries. Of course, I was just dragged along with my parents, but it was a good time to be interested in food.”

Roberts-Dominguez grew up cooking with her family. “Food was everywhere,” she said. When she was old enough to be home by herself after school, her mother started working, and Roberts-Dominguez started cooking dinners for the family.

Jan Roberts-Dominguez and Steve Dominguez have a building in their backyard where Jan displays her art. Credit: Don Haugen

Jan Roberts-Dominguez and Steve Dominguez have a building in their backyard where Jan displays her art. Credit: Don Haugen

Building a ‘microsyndicate’

After getting her undergraduate degree in San Luis Obispo in food and nutrition, Roberts-Dominguez’s plan was to teach. But after graduation she ended up living in Yosemite National Park and working at the grand old lodge, The Ahwahnee.

“I loved that experience,” she said. “It was kind of like my Paris.”

She later got a job at a test kitchen in San Francisco that was contracted by major food companies such as Campbell’s Soup and the National Frozen Food Advisory Board to develop recipes using their products, for the backs of boxes or labels. The director of that test kitchen was well-connected in the San Francisco food scene, and Roberts-Dominguez said she learned from the best.

After that, she moved to Corvallis to attend graduate school at Oregon State University. She got married, and started writing for the Corvallis Gazette-Times. That morphed into a column for The Oregonian, which was originally based on recipes in a local produce guide booklet she had written called “Green Cuisine,” which The Oregonian reviewed.

“After they reviewed it, I sent off a note thanking the editor,” she said, and asked if the paper would be interested in a column. They said yes, and that started a 35-year relationship with The Oregonian as well as the Gazette-Times.

“I called myself a microsyndicate,” she said with a laugh. “At the height of my syndication, I was in 18 papers around the West Coast and one in the East.”

In 1987, The Oregonian asked her to start writing a weekly preserving column, originally called “Green Cuisine” in reference to that booklet that started it all. The name later morphed into “Fresh Approach.”

After writing her column for a couple of years, Roberts-Dominguez decided to see if other papers around the Northwest and West Coast would be interested. She and her husband, Steve, who is a retired Environmental Protection Agency scientist, cold-called and drove to visit every newspaper they could, and many of them picked up her column, including the Santa Cruz Sentinel and the Moscow Idahonian. The Register-Guard picked up her column in 1995, and ran it for more than two decades, until 2017, when the newspaper industry as a whole began facing increasing challenges related to declining print readership and shifting advertiser spending.

One of Roberts-Dominguez’s most cherished memories from The Register-Guard years involves a reader named Marcia who called seeking her help recreating a beloved family recipe for lightly candy-coated hazelnuts that had been lost when Marcia’s elderly relatives had died. Roberts-Dominguez enlisted contacts within the hazelnut industry to help track down the recipe.

“That is one of my more fun food memories, because I know how important food is to people in holding onto family roots,” she said. “Eventually, recipes came to me through my friends. I tried a few, I found one and I mailed it off to her after I made it. She called me back and said, ‘You’ve given us our grandmother back,’ which was so sweet, really special.”

Jan Roberts-Dominguez’s backyard is a welcome space for outdoor cooking, gardening and showing off her artwork. Credit: Don Haugen

Jan Roberts-Dominguez’s backyard is a welcome space for outdoor cooking, gardening and showing off her artwork. Credit: Don Haugen Jan Roberts-Dominguez’s husband Steve built The Margaret, a large outbuilding where Jan displays her art rather than traveling to shows. Credit: Don Haugen

Jan Roberts-Dominguez’s husband Steve built The Margaret, a large outbuilding where Jan displays her art rather than traveling to shows. Credit: Don Haugen A print of a Jan Roberts-Dominguez watercolor called “Evening Flare III” of the Three Sisters in the Oregon Cascades. Credit: Don Haugen

A print of a Jan Roberts-Dominguez watercolor called “Evening Flare III” of the Three Sisters in the Oregon Cascades. Credit: Don Haugen A print of a Jan Roberts-Dominguez’s watercolor “High Summer,” showing Broken Top, the Three Sisters and Todd Lake from Mount Bachelor in the Oregon Cascades. Credit: Don Haugen

A print of a Jan Roberts-Dominguez’s watercolor “High Summer,” showing Broken Top, the Three Sisters and Todd Lake from Mount Bachelor in the Oregon Cascades. Credit: Don Haugen

Art and publishing beyond the column

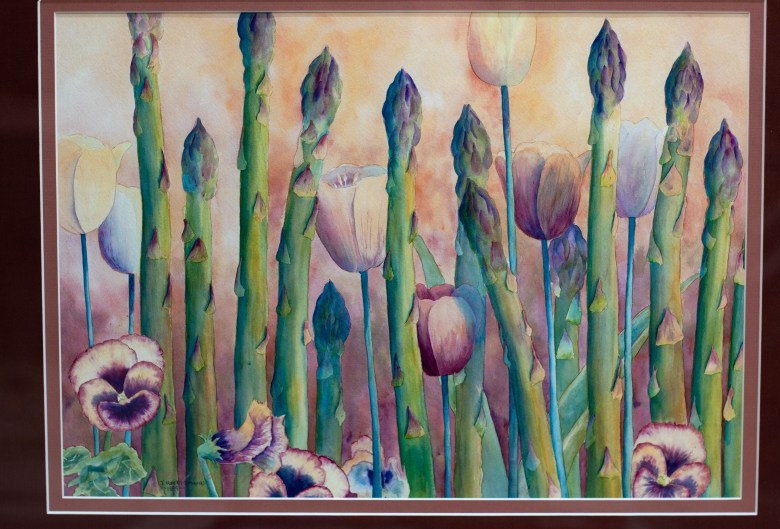

Through it all, Roberts-Dominguez was also creating art which printed alongside her weekly columns. If her column was about pickles, her art included watercolors of cucumbers.

“When I was trying to sell the column, it helped to have something beyond your words,” she said. “You had to be either a photographer or an illustrator, so I was an illustrator and I did line drawings. Then my editor at The Oregonian asked me if I would produce color art so they could use me on the cover of [its food section] Food Day.”

Jan Roberts-Dominguez created watercolor illustrations for both her columns and her five cookbooks. Credit: Don Haugen

Jan Roberts-Dominguez created watercolor illustrations for both her columns and her five cookbooks. Credit: Don Haugen

Watercolor was her medium for food art, and that eventually morphed into landscapes, which also paralleled her and her husband’s love for hiking. Roberts-Dominguez wrote five cookbooks, which also contained her illustrations. Her second, after 1983’s “Green Cuisine,” was “Sandwich Cuisine, Oregon Style,” in 1990. “The Mustard Book,” a small book all about making mustards, published in 1993, followed by “The Onion Book” in 1996.

“Oregon Hazelnut Country,” her fifth and last cookbook, is the one she is most proud of. This book was commissioned by the hazelnut industry, and Roberts-Dominguez was able to pick her own team to work on the book. The process of creating the hazelnut book was especially meaningful because she had creative control.

Her writing also opened doors to some remarkable experiences. Roberts-Dominguez was twice invited to Hong Kong’s Food and Wine Festival and spent 28 days as a guest chef on a Royal Viking cruise from San Francisco to Hong Kong, giving cooking classes while crossing the Pacific.

Perhaps most memorably, she secured a 45-minute private interview with Julia Child during a Portland food conference. Child had previously endorsed “The Mustard Book” by holding it up on the air on the TV show “Good Morning America.”

“I was worried that I would freeze up,” Roberts-Dominguez said. But after bringing up the TV presentation, she said Child was “very gracious” and eager to talk.

Roberts-Dominguez left The Register-Guard around 2017 as the paper was reducing freelance contributions.

“I was one of their last freelancers,” she noted.

She misses the collaborative relationship with editors that once defined newspaper work, and didn’t embrace the growing trends of blogging and social media. Over the years, Roberts-Dominguez worked closely with Register-Guard editors Paul Denison (“A really great editor to work with; I’m pretty sure he was the one who picked up my column,” she said), Jan Lafeman, Sara Marvin, Diana Elliott, Grant Podelco, and Bob Welch, who worked as an interim editor in the late ’90s who now writes for Lookout Eugene-Springfield.

Today, Roberts-Dominguez still finds joy in the kitchen. She treats cooking as both a hobby and stress relief. Professionally, though, she now focuses primarily on her watercolor landscapes.

Her husband, Steve, works as a framer for art and he built a large freestanding gallery in the backyard where Roberts-Dominguez displays her art for events and potential buyers. They call the 20-by-16-foot, high-ceilinged space “The Margaret,’’ as an homage to Roberts-Dominguez’s mother. Plus there’s a gallery adjacent to Steve’s framing studio, which they call The Microgallery.

“We built The Margaret as an answer to participating in outdoor art festivals,” she said. “It is a great display for my art and Steve’s framing, plus a wonderful venue for dinner parties! Especially in the winter.”

Steve’s framing business, Stoneyburn Framing, has no website, but Roberts-Dominguez says he’s a sought-after framer and works by appointment (call 541-752-7060 or email stoneyburn@proaxis.com). “People are always welcome to swing by our studio and gallery. Just call to set up a time to visit.”

Looking back on her career, Roberts-Dominguez takes pride in the connections she forged between food and community, between recipes and family stories. Her work helped establish Oregon as a region with its own distinctive food culture, from local produce to hazelnuts — and her columns inspired young people who were interested in food and food writing, like myself. Many people clipped her columns and tried her recipes, and enjoyed her art and her storytelling along the way.

Grandma Aden’s candied filberts. Credit: Vanessa Salvia / Lookout Eugene-Springfield

Grandma Aden’s candied filberts. Credit: Vanessa Salvia / Lookout Eugene-Springfield

Grandma Aden’s candied filberts

This recipe is included in Jan Roberts-Dominquez’s cookbook “Oregon Hazelnut Country – the Food, the Drink, the Spirit” and is used by permission. Fittingly, Roberts-Dominquez provided a story to go along with the recipe:

“This is the recipe that Marcia Stille asked me to find for her. It’s like the one her Grandma Aden in Wilsonville, Oregon, used to make and send to Marcia in Bend where she lived with her family. Now that the recipe has been revived, it has been appreciated by an even wider audience. A few years ago, says Marcia, ‘I was taking a graduate course at Portland State University and students were required to prepare and share with our classmates a special family food from our culture. I’m sure you’ve guessed by now what mine was — everyone just loved them and the story they came with.’

Even without a link to the past, these are a wonderful treat to make, especially during the holidays — both as gifts and to have on hand when friends drop by.”

Makes 3 cups

3 cups shelled hazelnuts

1 tablespoon butter

4 tablespoons light Karo syrup

Place hazelnuts on a jelly roll pan and toast in a 350-degree oven just until very pale golden brown and the outer papery skins are beginning to crack and separate from the nut.

Remove from oven and let cool. Pour into a large terry cloth towel and either fold it over or place another towel on top. Rub vigorously back and forth through the towel to peel away the skins from the hazelnuts. This can be done several days ahead and the nuts stored in an airtight container.

When ready to candy the hazelnuts, preheat the oven to 225 degrees. Place the 1 tablespoon of butter in the center of a jelly roll pan (or any baking sheet with sides), and put the pan in the oven to melt the butter. When the butter has melted, mix in the Karo syrup, then add the skinned nuts.

Sprinkle lightly with salt and, using a wide spatula, stir the nuts around in the syrup/butter mixture to evenly coat the nuts and spread them into a flat layer in the pan.

Begin roasting the nuts, stirring about every 5 to 7 minutes so they stay evenly coated with the syrup as it cooks. Cook for 20 to 30 minutes.

In preparation for cooling the nuts, spread a large sheet of waxed paper or parchment paper on the counter. Then, when the nuts are a lovely golden brown, remove from the oven and pour them out onto the paper to cool, quickly spreading them apart so they don’t touch each other during cooling. (It’s not a tragedy if some stick together; they break apart very easily after cooled.)

When the nuts are completely cool, store them in an airtight container.

Related

Dining and Cooking