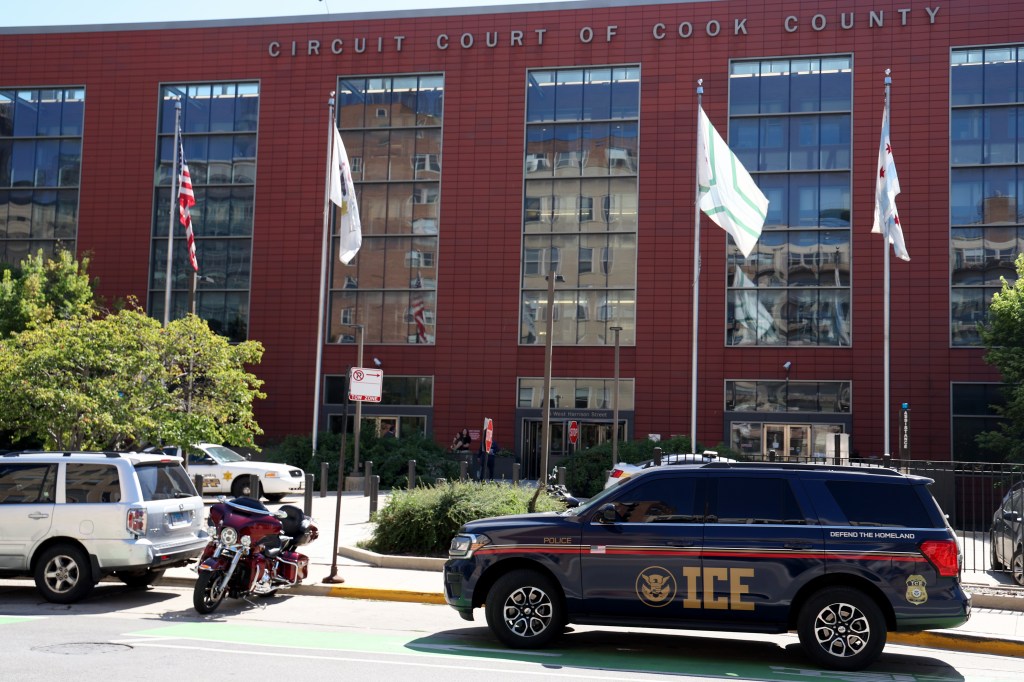

Cook County commissioners are calling on other county officeholders to help sound the alarm if federal immigration agents turn up at county courthouses and other public facilities, but many officials so far aren’t on board with offering that help.

The county board members made the request in a just-passed county resolution denouncing deceptive tactics from Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Protester, including Lee Goodman, in stripes, stands outside of the Domestic Violence Courthouse in Chicago, Sept. 4, 2025. (Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune)

Protester, including Lee Goodman, in stripes, stands outside of the Domestic Violence Courthouse in Chicago, Sept. 4, 2025. (Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune)

ICE agents detained two people in recent weeks at Cook County domestic violence courthouses, triggering fears the incidents would have a chilling effect on victims or their families and deter them from appearing in court. Commissioners want people to know if the agents have been spotted around government buildings so they know whether to stay away.

The nonbinding resolution requested “official communication of interactions related to immigration enforcement that occur within County buildings, on County property, or with County staff from all Cook County agencies, departments, and bureaus.”

Public Defender Sharone Mitchell has asked the board and other county offices to consider “limiting immigration enforcement inside and around court locations, ensuring federal enforcement action taking place inside county buildings can be documented for accountability,” and ensuring Circuit Court rules guarantee the option for remote court attendance “for appropriate hearings in all court rooms,” according to a letter filed with the county board.

Other officials have not been so clear about their stance on the situation.

Asked whether the Office of the Chief Judge had an internal policy or protocol to respond to ICE activity in courthouses or county property, spokeswoman Mary Wisniewski declined to comment. Asked the same, Circuit Court Clerk Mariyana Spyropoulos’ spokeswoman Rowida Zatar said the office coordinates “with all justice partners and refer(s) communications” to the Justice Advisory Council under Board President Toni Preckwinkle’s office, but declined to clarify what communications they were referring to or expand on their internal policy for handling ICE.

Mitchell’s office, which always speaks for defendants, also has a small team of attorneys working on immigration cases. His voice has been one of the strongest among county leaders on the issue, along with county Commissioners Jessica Vasquez and Alma Anaya, the chief sponsors of the resolution.

They joined immigration advocates, Board President Toni Preckwinkle, and more than half of the county board at a Wednesday press conference to decry immigration enforcement officials’ practices — the use of unmarked cars, officers wearing plain clothes, covering their faces, and declining to provide information in their official capacity — as running counter to fundamental due process rights.

Vasquez and Anaya said one of their goals is to share information with on-the-ground networks that share alerts for ICE activity.

The policy at Cook County Health, which falls under Preckwinkle’s jurisdiction, calls for staff to ask immigration enforcement authorities to wait in the lobby if they appear, request an agent’s identification and not consent to any enforcement activity on the premises. Staff should then contact CCH police, the facility manager, the on-duty administrator at the hospital or clinic, and CCH’s legal team.

They do not release patient information or allow anyone to enter patient care areas unless the agent has a valid, signed judicial warrant that has been confirmed by CCH’s legal team.

So far, spokeswoman Alex Normington said, there has not been ICE activity at CCH facilities. Since February, they have met with immigration advocacy, labor and government partners on immigration issues, including increased federal enforcement. Normington noted patients concerned about potential enforcement can speak with doctors on the phone or use the county’s telehealth services for non-emergency visits.

The county Forest Preserves, also under Preckwinkle’s umbrella, has a similar policy. They received reports that ICE gathered briefly in a parking lot, and left shortly after Forest Preserve police arrived. Their three-page guidance for employees emphasizes that staff should not put themselves in “a position that leads to a confrontation or altercation,” if ICE arrives.

“Respectfully request that the agents wait until a supervisor arrives,” it reads. “Do not interfere with or obstruct the agent’s actions, even if they refuse to wait for your supervisor. Document their refusal to wait. If asked, do not consent to the entry into or search of restricted or limited access spaces. As an employer, the Forest Preserves does not consent to federal immigration agents entering any restricted access or limited access spaces without proper legal authorization.”

Supervisors should politely ask for identifying information from the agent in charge, make a copy of their warrant, and if allowed, accompany agents in a search and take notes of what items were seized.

The Cook County Sheriff’s Office declined to provide information about any changes to its policies in light of the county board resolution. “Existing state law and local ordinance have long outlined our Office’s responsibilities regarding federal immigration regulatory programs, and we will continue to follow all local, state, and federal laws,” said Grace Cronin, spokeswoman for Sheriff Tom Dart.

The office is required to document, but decline ICE requests to hold detainees unless agents have a criminal warrant unrelated to immigration laws. They are also barred from communicating with ICE regarding individuals’ incarceration status or release dates while on duty.

Through mid-September, the office received 378 such requests, already exceeding the 314 total requests from last year, according to Sheriff’s Office figures received via an open records request.

Matt McGrath, spokesman for Cook County State’s Attorney Eileen O’Neill Burke said the office has serious concerns that ICE enforcement at courthouses “may discourage victims and witnesses from coming to court, undermining our ability to seek justice in the process — and we are currently developing updated guidance for our Victim/Witness specialists.”

The office is a tenant in the courthouse and does not otherwise have a distinct policy for when ICE officers are present or making arrests, McGrath said.

New York’s 2020 Protect Our Courts Act bars ICE from making civil arrests at state and municipal courthouses without a judicial warrant. But the law drew a court challenge from President Donald Trump’s Department of Justice earlier this summer. They argue conducting enforcement near courthouses cuts down the risk of arrestees running away and “potential safety risks” to the public and officers because of the extra security screening that happens at court, and generally, that obstructing immigration activities violates the law.

Originally Published: September 19, 2025 at 2:26 PM CDT

Dining and Cooking