Besides, my real heroes weren’t American but French: Paul Bocuse, the visionary of Lyon; the formidably articulate Joël Robuchon; the Troisgros brothers, renowned for their salmon with sorrel sauce; Michel Guérard, the inventor of cuisine minceur, a low-calorie version of nouvelle cuisine. I was fascinated by Bernard Loiseau, the moody creator of cuisine à l’eau, a style built around water-based sauces. (He later killed himself, fearing that he was about to lose his third Michelin star.) But the chef who most seized my imagination was Alain Senderens, a bearded, bespectacled intellectual who looked more like a post-structuralist theorist or a Kabbalah scholar than like a cook. At L’Archestrate, in Paris, he made daring adaptations of recipes he excavated from ancient Roman cookbooks, and shocked the culinary establishment with wonderfully mad flavor combinations, like lobster with vanilla sauce.

I was in awe of Senderens. Not that I’d ever tasted his food—I hadn’t even been to Paris—but merely to read about Senderens was to know that he was a genius. I discovered him thanks to my favorite food critics, Henri Gault and Christian Millau, who ran an opinionated, witty, literary rival to the staid Michelin Guide. They declared Senderens “the Picasso of French cooking.” He was certainly my Picasso, a bold and uncompromising revolutionary who’d reinvented the language of food.

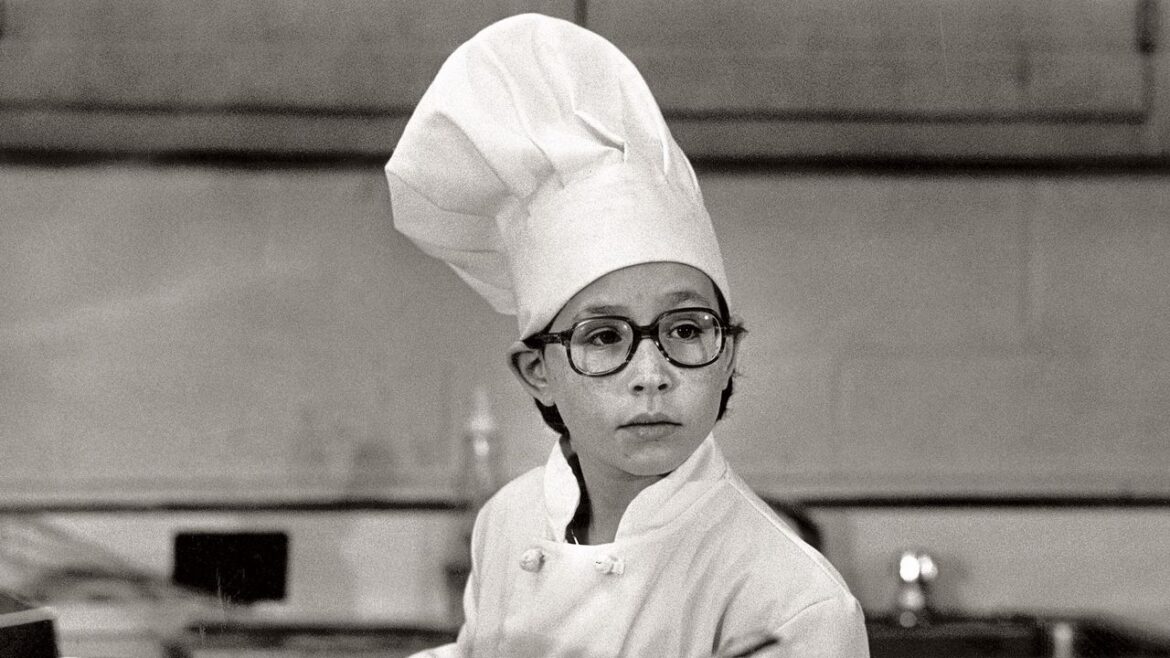

My own cooking was more cautious. I was attached to traditional forms and intent on pleasing. I recently unearthed the menu for a dinner party I catered when I was maybe fourteen. The dishes—“Fricassée of Mussels with Yellow Pepper Cream and Spinach” or “Summer Fruits with a Sabayon Sauce Flavored with Framboise”—show that I was more interested in absorbing the great tradition of French cooking than in disrupting it. How could I break with a tradition if I hadn’t properly learned its techniques? Boning poultry, cutting perfect julienned carrots, peeling and dicing a tomato unblemished by skin or seeds, making a lumpless roux for béchamel, caramelizing onions without burning them, whisking pieces of butter into a wine reduction without curdling the sauce: such skills had to become second nature, like tying one’s shoes or swimming breaststroke.

These are physical as much as intellectual forms of knowledge. How do you know that a steak, or a piece of salmon, has been cooked to your liking? Not by a timer, or even by looking, but by the feel of its flesh when you press it, and the indentation left by your finger. I began to keep a food diary, charting my progress and recording my innermost thoughts about cooking. I was interested in its relationship to art and politics, both growing enthusiasms, and to sex, an unknown terrain that I was impatient to explore. (One of my friends came across a cassette I had made, full of poetic confessions about food and sensuality; after enduring hours of ridicule, I destroyed it.)

In the kitchen, I sought out meats that I’d never eaten—rabbit, quail, pigeon—and discovered the voluptuous frisson of offal, on the delicate line between succulent and repellent. There were a few disasters. Once, I made pasta with chanterelles that had been picked in a forest in Maine by a family friend, an old Russian Jew who claimed to be a mycologist. Suddenly, my grandmother said she felt sick and started to panic. Everyone put their forks down. The mushrooms turned out to be fine. While my parents made sure that I hadn’t poisoned my grandmother, I went back to the kitchen and whipped up a simple spaghetti aglio e olio, which I secretly preferred to chanterelles.

Not long after Reichl’s profile appeared, I found a French culinary mentor, Gérard Pangaud. In Paris, he’d become, at twenty-seven, the youngest chef ever to receive two Michelin stars. Then Joe Baum, the themed-restaurant pioneer, persuaded him to come to New York and head the kitchen at Aurora, on East Forty-ninth Street. The restaurant was a chic and dreamy midtown oasis in muted shades of blue and pink. Bryan Miller, the restaurant critic for the Times, called it “the Versailles in Joe Baum’s impressive collection of culinary chateaus.”

I first went there for lunch with my grandmother, after writing Pangaud a fan letter. He was waiting when we arrived. For the next few hours, we ate rounds of lobster tail in a tangy, buttery sauce of Sauternes, lime, and fresh ginger, on a bed of spinach; a ragout of periwinkles, briny as the sea; and slices of grilled, rosy-pink pigeon breast with olives, tomato, and lemon confit, in a rich, sombre sauce that haunted the tongue. Pangaud wasn’t a revolutionary like Senderens, but he had a grippingly visceral imagination, an intuition for unusual combinations of flavor and texture, and an earthy elegance. After lunch, he invited me to study with him.

There was nothing unusual about a chef asking a teen-ager if he’d like to work in the kitchen. In France, culinary training is based on what’s known as the stage, an unpaid apprenticeship that all chefs pass through, beginning with the lowliest of activities and gradually rising to more complex tasks. French kitchens are deeply hierarchical institutions, run along essentially military lines. My studies with Pangaud weren’t quite a stage—living in Massachusetts, I could train for only a few days every couple of months—but my education there lasted several years. The days began at dawn and ended well past midnight, and I made the most of them. I usually worked in garde-manger, preparing salads and chopping vegetables, but I was occasionally allowed to work on the line, searing steaks, duck breasts, and thick slabs of foie gras.

Dining and Cooking