If you go to a restaurant today, odds are you might not even get a menu when you sit down at your table. Since the pandemic, QR codes have become more common and easier for restaurants.

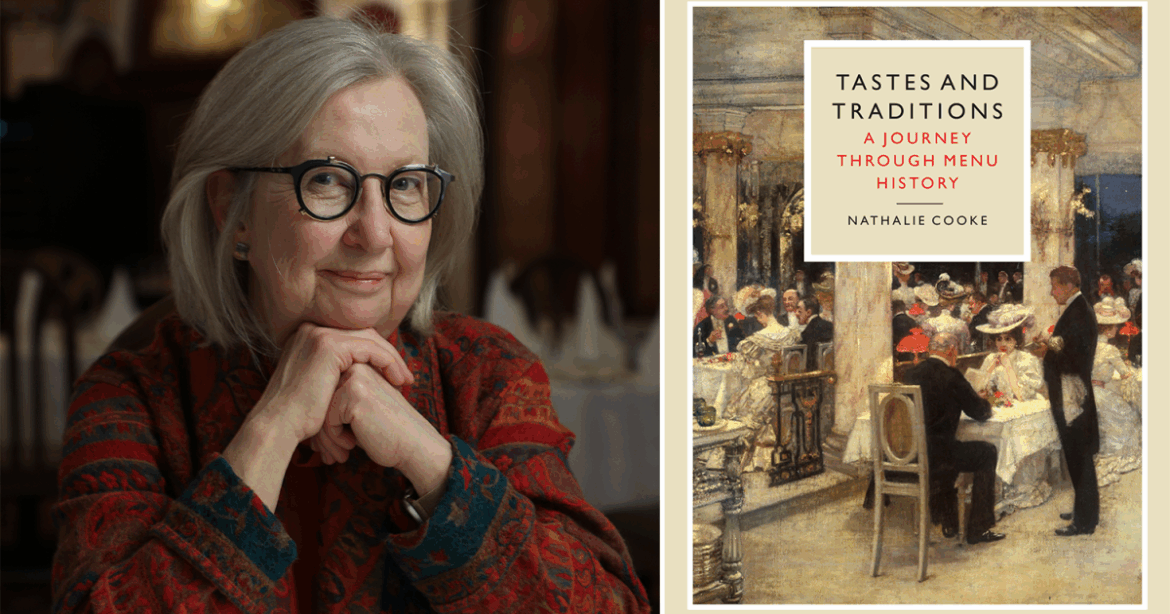

But, our next guest is invested in the real thing. Nathalie Cooke is an English professor at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and author of the new book “Tastes and Traditions: A Journey through Menu History.”

In it, she views menus as historical documents and cultural artifacts, revealing meals eaten by kings and gods, during sieges and banquets.

She spoke more about it with The Show, including what sparked her interest in something as niche as historic menus.

Full conversation

NATHALIE COOKE: Well, you know, I’m an English professor, so I actually do look at different forms of storytelling. So I’m interested in how the form shapes the story. So a story told in a sonnet, for example, is quite different from a story told in a Victorian novel, and the form actually shapes that story.

And so I do look at food history. I’m interested in it. And I suddenly looked at a menu and I thought, you know, this is a form, rather the way a sonnet is a form for poetry. It just, it has so many more levels because it has different languages and it has images and it has graphics and font and lots of other different layers that you can peel back to understand. Very sophisticated stories.

LAUREN GILGER: Very interesting. All right, and we’ll get to some of those layers as well. But I want to begin with some of the dishes at hand, because really what you’re at here is food as well, right. You take us way through history in this book as well. Some very old menus that you’ve dug up, handwritten ones, you know, ones from banquets and things for kings and gods that reveal, I think, some surprising things that people have eaten over time.

Start with a few of your favorite dishes throughout history that you uncovered here.

COOKE: What a terrific question. So actually, the meals for kings, I’ve looked at a wonderful menu from 1757 from the Chateau de Choisy, and that was before they actually needed menus because all the food was laid on the table for the lucky few who the king invited to share the meal with him. I do look at meals for the gods.

I was fascinated by that when I went to Thailand. You know, those spirit houses and how they have food essentially, that the gods eat and do that food disappears daily because it’s a way of feeding the poor to a certain extent, you know.

GILGER: That’s fascinating.

COOKE: And then the other one is when you talk about strange food, one of the menus I start with is a menu from 1870 it’s a Christmas menu again for royalty. Only this time, there’s some really unusual things being served. So there’s something called consommé d’Eléphants. Elephant consommé. Or civet de kangourou, which is essentially kangaroo stew.

GILGER: Wow.

COOKE: And I can keep going, you know, side of bear. So once you actually look at this menu, it’s from a very sophisticated Parisian restaurant that we know today, Le Restaurant Voisin. But it’s actually the 99th day of the siege of the Paris, and it’s when they’re reduced to eating the zoo, and so the royalty sit down and start to eat the zoo animals.

It’s very sad, but the language of French cuisine persists. So normally one would get a civet of liévre, which is, in other words, a hare stew, but they’ve chosen to make it kangaroo stew because they’ve chosen another animal that hops.

GILGER: Wow.

COOKE: Yeah. So the idiom of French cuisine persists despite essentially the larders being bare.

GILGER: Wow, that’s fascinating. As you’re getting at here, like, this is more than about interesting dishes, though. Like, the menus, the food being served says a lot about the moment they come from in history, the culture, cultures they came from. You call menus cultural artifacts, right?

COOKE: Yes. I mean, when we look at historical documents, I mean, we think of looking at cookbooks, and we think, wow, that gives us a glimpse of what people ate then. But in actual fact, cookbooks, they’re aspirational. They’re. They’re books about what one should cook or what one might cook. It doesn’t necessarily tell you what people are cooking in their own kitchen, unless it’s got so many splatters on it and so many, you know, handwritten notes that, you know, somebody has done that.

But menus, menus are fabulous historical documents. They, they typically have a date, they typically have a location, the particular restaurant. They typically have a language, and it’s not necessarily the language of the diners or the restaurateurs. So, you know, I’m speaking to you in Phoenix. If we go back to some old restaurants from Phoenix, we’ll see something called menu French.

Right. And it’s not real French. It’s just to make it sound more sophisticated, because French cuisine is understood to be haute cuisine.

GILGER: Still true. Still true here.

COOKE: I think it probably is. But you know what? Jackie Kennedy did a wonderful thing in the White House. She started to transform the language of White House menus into English. And that was a, that was a significant moment.

GILGER: Wow.

COOKE: And Roosevelt hosted King George just before World War II, as a kind of diplomatic moment, and served hot dogs on the White House lawn. Right. In a menu that was not French, it was English.

GILGER: A big turn. One thing I wanted to ask you about, Natalie, is the, the chapter on health on the menu. Right. Like the changing perceptions that you can read throughout these menus in time of what’s healthy, what health means. Like cigarettes and cocaine laced Coca Cola used to be on the menu, right?

COOKE: Well, in fact, cocaine laced Coca Cola was actually listed under nutritious drinks in one restaurant in the 1920s. And definitely we had cigars and cigarettes. And probably in the future we’ll look back at contemporary menus with significant range of alcohol and we’ll be concerned about that too.

But one of the things that surprised me, I started that chapter thinking I was taking pride in the fact that we know much more about health now than they did then. And I was assuming we would have much more detail about emergent medical knowledge and it would show up on the menus.

But in actual fact, I found considerable consistency over time. So that the principles of moderation, you know, moderate consumption, balanced diet, significant amount of vegetables, significant amount of natural products is something that we see not just over decades, but over centuries.

GILGER: One thing you uncover is that vegetarianism, even veganism, like, has been around for a lot longer than I would have assumed.

COOKE: Absolutely. And that’s. And I did that in part as a kind of rebuttal to students who felt that that was, you know, very much a diet at the moment. Right. So I went back and I looked at menus from the 1880s, the mid-1800s. You know, I looked at the menus that were developed by Kellogg’s and by a number of the, of the researchers who were starting to provide cereals as significant kind of grain. And I traced that through the decades to show that it’s really been very persistent.

GILGER: All right, I want to end with a broad question, I guess, which is about the, I guess the why here, right. Like, you’re pulling up a lot of very interesting history, a lot of interesting trends, a lot of counterintuitive narratives, but it’s more than food, right. Like, this is about the human desire for something more meaningful.

COOKE: Absolutely. So let me turn that around a little bit and say, let’s forget about menus for a moment and think about meals. And actually the choice of what we eat, who we eat it with, when we eat, is a way of actually telling a story in a non-verbal language. And so that’s how we make culture.

That’s how culture is made through those stories. And so the menus give us a glimpse of the way some of those stories were told through meals and through food choices in the past. And all I do in this book is I suggest not only that we pay attention to meals in the past through these wonderful documents, but what I’m actually trying to do is suggest that we pay close attention to contemporary meals and the stories that we are telling one another through food choices.

KJZZ’s The Show transcripts are created on deadline. This text is edited for length and clarity, and may not be in its final form. The authoritative record of KJZZ’s programming is the audio record.

Dining and Cooking