His just-published book puts as much emphasis on his painting as on his food. “The Art of Jacques Pépin, The Cookbook: Favorite Recipes and Paintings from My Life in the Kitchen” presents sketches of produce, fruits, herbs, seafood; photos of sculptures, landscapes, seascapes, flowers, even abstract compositions.

“My two primary passions remain cooking and painting,” he writes. “I think of each of them as a form of art.”

Today in his kitchen, perched on a stool before a wall of copper and stainless pans (“I only use the stainless now; the others are too heavy”), he’s working on a menu for actor and designer Isaac Mizrahi, who is hosting a dinner in his honor. “I sang on his show‚” says Pépin, amused. (Is this yet another talent?) He draws menus for many events, listing the dishes in distinctive, curly penmanship.

The open space here is large and warm with a dining table and sitting area. Pépin is at a massive granite-topped island, the one he works at when he’s doing one of his short cooking videos, filmed by his longtime photographer and affable friend, Tom Hopkins, who has stopped by today to go over a project. Gaston, Pépin’s beloved miniature black poodle, dozes nearby.

Jacques Pépin at home in Connecticut, where he cooks and paints. “My two primary passions remain cooking and painting,” he writes in his new book. Barry Chin/Globe Staff

Jacques Pépin at home in Connecticut, where he cooks and paints. “My two primary passions remain cooking and painting,” he writes in his new book. Barry Chin/Globe Staff

On his cellphone, Pépin opens Facebook to check which cooking video is running today. He’s made hundreds, started during the pandemic and becoming wildly popular when his daughter, Claudine, posted them. “I have 1.9 million followers,” he says. He seems surprised. The videos are now also on YouTube and Instagram.

Claudine is president of the Jacques Pépin Foundation, working with her husband, Rollie Wesen, to support free training programs for people who want to become cooks but may not have the resources to undertake the study.

Kelsey Whitsett, Pépin’s cheery and energetic assistant, also his recipe editor for the videos, among other responsibilities, has given him printouts of their grueling schedule for the following week, when they’ll fly to Napa Valley, Calif., where a half-dozen chefs are hosting benefit dinners in his honor. Some diners will pony up thousands to attend.

“Here are the restaurants,” he says, showing me a sheaf of papers that includes an event at the French Laundry in Yountville, Calif., on Nov. 1 ($5,000 per guest; there’s a waitlist).

These chefs, and others around the country, including many home cooks, are part of 90/90 (90 chefs, 90 dinners), a fund-raising initiative for his foundation.

Chef Jacques Pépin (left) and his late wife, Gloria, who he was married to for 54 years.Jacques Pépin/ Facebook Page

Chef Jacques Pépin (left) and his late wife, Gloria, who he was married to for 54 years.Jacques Pépin/ Facebook Page

On Dec. 18, his birthday, he won’t be far from home, where he and his late wife, Gloria, who died in 2020, set up housekeeping 50 years ago in an old brick factory. That night, they’ll be at nearby Madison Beach Hotel (also sold out).

Pépin had humble beginnings in Bourg-en-Bresse, near Lyon in France, where his mother was working as a waitress during World War II and later opened her own Lyon restaurant, Chez Pépin. Jacques left school at 13 to become a kitchen apprentice.

His job as chef to President de Gaulle in 1958 resulted from a series of incidents during the fragile Fourth Republic. He was 21, in the French Navy, cooking at the French Treasury, when the government toppled and his boss became prime minister. He moved to the Matignon, the PM’s official residence.

Jacques Pépin, age 16, proudly displays poached fish at the Firemen’s Ball of Bellegarde, France, the first banquet he prepared solo.

Jacques Pépin, age 16, proudly displays poached fish at the Firemen’s Ball of Bellegarde, France, the first banquet he prepared solo.

Then another government, another topple, a third, another collapse — meanwhile Pépin was toiling away at the Matignon — when General de Gaulle was installed as president. From then on, Pépin’s dinner instructions came directly from Madame de Gaulle, affectionately called Tante Yvonne by the people.

The de Gaulles ate plainly, and though Pépin later cooked in top kitchens, including New York’s famed Le Pavillon, he has always retained a deep respect for simple food, the kind of fare his mother served. At KQED, he says, “I did 13 series called ‘Fast Food My Way,’ to show people how to use the supermarket as prep cook.”

When Le Pavillon closed, he turned down a job offer from Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. whose son was headed for the White House, instead joining a former Pavillon colleague, Pierre Franey, who had gone to work for Boston-born Howard Johnson. The entrepreneur owned Howard Johnson’s, a growing chain of family restaurants. All the food, made from scratch, came from a commissary run by Franey and Pépin.

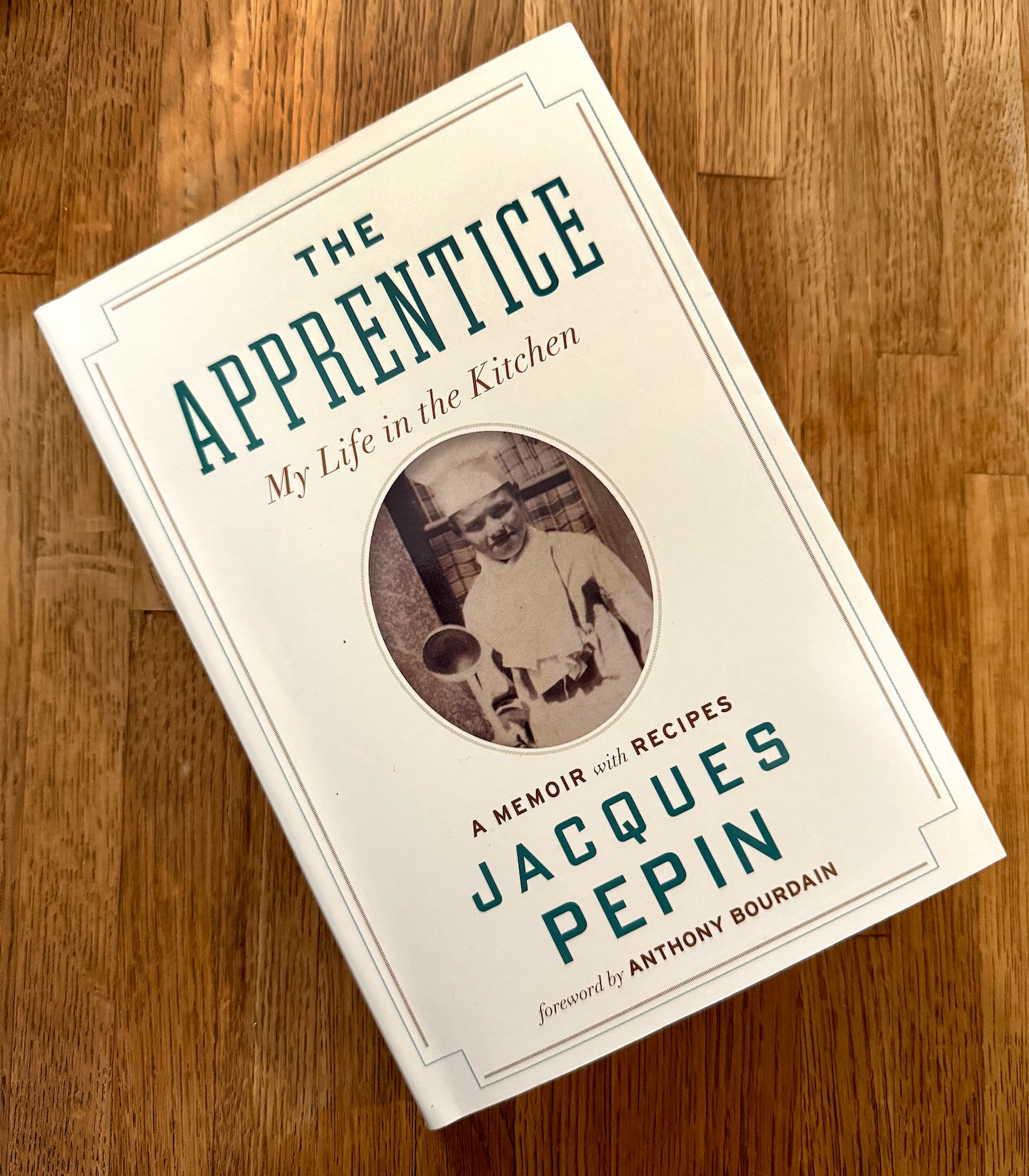

“The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen,” one of Jacques Pépin’s many books.Barry Chin/Globe Staff

“The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen,” one of Jacques Pépin’s many books.Barry Chin/Globe Staff

“It was Camelot versus HoJo’s,” he writes in “The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen.” Rather than cooking for the new American president, he chose to feed travelers along the newly completed Interstate highway system. He has called it his “American apprenticeship.”

“I worked there for 10 years from the ’60s to the ’70s,” he says. Pépin has a striking memory, reeling off dates, numbers, places, names, with facility. “I had never worked with chemists. I started with six chickens in a test kitchen and finished with 3,000 pounds of chicken.”

Operating at that scale — at the time Howard Johnson’s fed more people than McDonald’s, Burger King, and Kentucky Fried Chicken combined — gave Pépin the skills to open his own soup restaurant, La Potagerie, in New York’s Midtown. There were lines around the block. He was 39.

One night, driving home alone from the city to Hunter, N.Y, where he and Gloria lived, his car hit a deer. “I should have died,” he writes in “The Apprentice.” After a long recovery, he had to give up the demands of a professional kitchen.

He later worked for restaurateur Joseph Baum, opening establishments at the World Trade Center, which fed 30,000 people a day. “I would never have been able to do that before Howard Johnson’s,” he says. He became a culinary instructor on the professional level, teaching at the French Culinary Institute and helping establish at Boston University (with Julia Child and the university’s Rebecca Alssid) a Master of Arts in Gastronomy (I teach food journalism in the program) and the Culinary Arts program.

Julia Child cooking with Jacques Pépin in her Cambridge kitchen in 1999.KREITER, Suzanne GLOBE STAFF

Julia Child cooking with Jacques Pépin in her Cambridge kitchen in 1999.KREITER, Suzanne GLOBE STAFF

Though Pépin can bone a chicken in minutes, make complicated French dishes that evoke Escoffier, and turn out restaurant food in his sleep, the food he seems most interested in these days is simple, budget-friendly, and full of flavor.

His techniques are often those he’s figured out, not just the French culinary canon. In his new book, he sautes chicken thighs by setting them skin down in a dry pan, covering the pan, letting the fat under the skin release and brown it, and adding spinach to the juices to produce a very quick, remarkable dish.

While most chocolate mousse recipes contain raw eggs, which can be problematic for some diners, Pépin’s Crème au Chocolat adds a little flour to the custard, so he can boil it (raw eggs begone). It’s rich, chocolate-y, and creamy, though only milk is used.

I ask Jacques to point out his favorite kitchen tools. He pulls out drawers with painted platters, done with a Sur La Table collaboration, opens cabinets with impressively big pots, shows me a large tile backsplash above the stove that he hand-painted. A rack in the granite counter holds over a dozen knives (he routinely uses only three).

Nonetheless, Pépin insists, “My hands are the most important piece of equipment. I can squeeze, pull, and tear.” He holds out his hands, strong worker’s hands that have seen a lot of life, that have cooked for heads of state and ordinary people with equal respect.

And beautiful hands they are, Chef. We all insist on calling you Chef.

Sheryl Julian can be reached at sheryl.julian@globe.com.

Dining and Cooking