Driving up a rutted dirt road in a white 2003 Chevy Silverado pickup with 365,000 miles on it, Bob Tillman of Alta Colina (opens in new tab) wines wanted us to see what makes Paso Robles a magical place.

From the summit of his rugged property — a high-elevation, 130-acre plot where he cultivates grenache, syrah, and mourvèdre grapes (the esteemed Rhône Valley trio known as GSM (opens in new tab)) — neat rows of vines sprawled in every direction. The landscape looked eternal, but compared with Napa or Sonoma counties, let alone Provence, Paso Robles’ wine industry is a newcomer. Until the turn of the century, the region was known for olives and ranching.

Grapes came later. When Tillman acquired the property in the early 2000s, “you could not see a vine,” he said. “Paso has blossomed in the last 20 years, and it’s been a joy to be part of it.” He drove us back to the winery’s parking lot. Only hours later, his team began the season’s harvest.

McPrice Myers Wines in Paso Robles grows affordable yet high-quality cabernet and zinfandel.

McPrice Myers Wines in Paso Robles grows affordable yet high-quality cabernet and zinfandel.

Today, there are more than 300 wine producers in and around Paso Robles, which sits almost equidistant between San Francisco and Los Angeles on the 101. Blessed with chalky soils, hot days, and comparatively cool nights, Paso Robles has become the epicenter of California’s “other” wine country, the Central Coast, which stretches roughly from Santa Cruz to Santa Barbara. Over the last 25 years, wine has fueled the region’s economic growth and population boom, even as Napa encounters economic uncertainty (opens in new tab) from overindexing on grapes.

But Paso Robles’ unique terroir can’t avoid one uncomfortable fact: Study after study indicates that Americans, particularly those under 35, are drinking far less (opens in new tab). On the strength of its cabernets and zinfandels, Paso has only recently come into its own as a high-end travel destination. Now it faces the question of how it will continue to thrive.

A local getaway with no car needed

Famed for its hot springs with allegedly curative properties, Paso was founded as a 19th century resort town. As the appeal of “taking the waters (opens in new tab)” faded, agriculture came to dominate the local economy. As a result of this history, railroad tracks still pass through town, a relic repurposed as a tourism asset. And though Californians famously love their cars, Amtrak is the way to go, with tickets as low as $33 one way from the Bay Area.

My fiancé and I hopped the 9:09 a.m. Coast Starlight (opens in new tab) from Jack London Square to Paso Robles, arriving a little before 2 p.m. It was 30 degrees warmer than when we’d left Oakland. An Amtrak virgin, I was an instant convert to the thrill of medium-distance train travel. It’s everything a trip by plane or car is not: spacious, with reliable Wi-Fi and the freedom to move around. It’s wonderful to stretch out in your seat and watch the Salinas River wetlands pass by, no seatbelt (or security screening) required.

Patrons enjoy the courtyard of the Paso Robles Inn.

Patrons enjoy the courtyard of the Paso Robles Inn. A meal at The Alchemists’ Garden.

A meal at The Alchemists’ Garden.

A weekend in Paso without a car is easy, especially outside the summer months, when afternoon temperatures can hit the triple digits. Rideshares are plentiful, and the train station is just south of the compact, walkable downtown, which, like Healdsburg in Sonoma County, is arranged around a square called Downtown City Park. It’s dense with restaurants at all price points, from family-run Middle Eastern joints (opens in new tab) to Fish Gaucho (opens in new tab), an upscale cantina with hundreds of mezcals and tequilas.

Excellent cocktails and Michelin-starred restaurants

Wine is the focus, but not to the exclusion of all else, with art galleries across town and Sensorio (opens in new tab), a massive light-art installation, just outside it. Upscale lodgings abound. This week, the 2-month-old luxury hotel The Ava announced the debut of Emre (opens in new tab), a live-fire-driven Mediterranean restaurant. Paso also has a clutch of bars, ranging from a rustic, un-air-conditioned saloon (opens in new tab) to the kitschy Cane Tiki Room (opens in new tab) within walking distance of the main square.

Just off the central green space, the 5-year-old, indoor-outdoor restaurant The Alchemists’ Garden (opens in new tab) offers some of the most complex cocktails I’ve had in California. Co-owner and bar director Tony Bennett created a rotating menu based on zodiac signs, each available for a month at a time. The Libra combines dill-infused vodka, Greek yogurt, lemon, ginger, rose-hip liqueur, and sweet potato espuma. Pouring one is a multistep process: For the espuma, Bennett runs sweet potatoes through a macerating juicer and processes the resulting liquid with brown sugar and a mix of 15 spices, then adds emulsifying agents to obtain a foam. (There are lots more steps, but you get the idea.)

On busy weekend nights, he might serve 300 to 400 people. Almost everyone comes to town for wine, but “the lucky accident that turned Paso into what Paso has become is that we offer so much more,” Bennett said. “Our cocktail culture isn’t just sweet-and-sour from a gun. We’re making something better.”

Fine dining is another area of growth. Of California’s four Michelin-starred restaurants not located in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, two — Six Test Kitchen (opens in new tab) and The Restaurant at Justin (opens in new tab) — are in Paso. Just off the square, the Paso Robles Inn, among the city’s most historic properties, scored a big win when prolific chef (opens in new tab) Charlie Palmer signed a deal to take over its steakhouse. Palmer, who has numerous restaurants in New York and Las Vegas, plus one each in Napa and Sonoma, will begin renovations in January. According to hotel GM Erica Fryburger, the restaurant will be called The Path by Charlie Palmer and will feature partnerships with local winemakers.

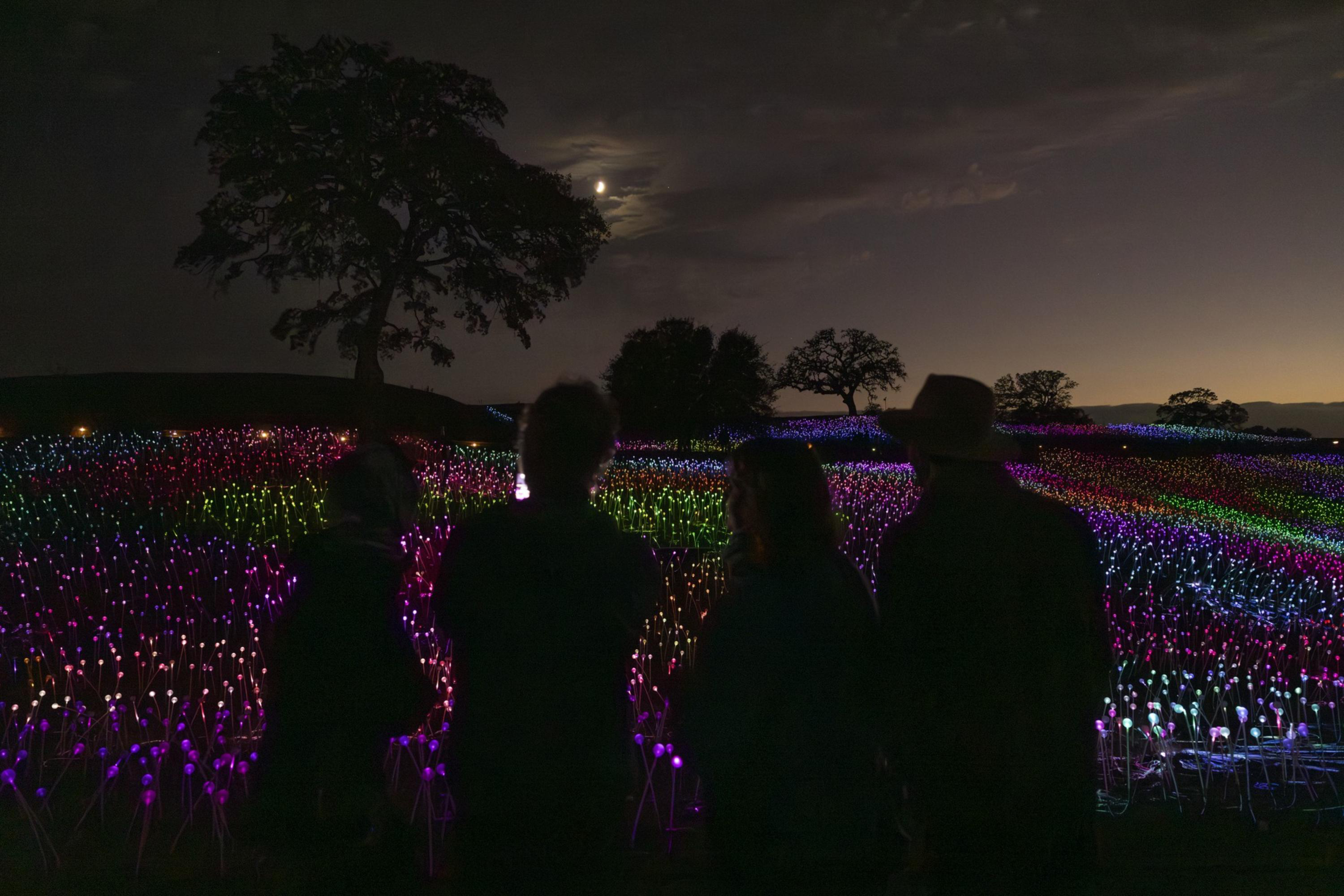

Elsewhere, Paso is taking strides to diversify its appeal beyond food and drink. Among the biggest draws is Sensorio, the 6-year-old, 35-acre light-art installation a few miles east of town that evokes the rainbow sugarcubes of San Francisco’s own Charles Gadeken. The centerpiece is the “Field of Light,” an undulating expanse of 100,000 solar-powered flowers that gradually change color. (It’s particularly beautiful immediately after sunset.) There are seven made-for-Instagram exhibits in all, none of which would be out of place at Burning Man, plus a cafe and a stage for live entertainment.

A view of “Field of Light” at Sensorio.

A view of “Field of Light” at Sensorio.

According to GM Ryan Hopple, long-term plans for Sensorio include a fine-dining restaurant and hotel, and last month, the owners put out an open call for artists to submit proposals for additional exhibits. “We’re hoping for more immersive art for people to — pardon the pun — make their memories glow,” Hopple said.

Attracting younger wine drinkers

Meanwhile, some wine growers are reorienting their approach for a new generation of drinkers. At McPrice Myers (opens in new tab), a producer west of town known for affordable yet high-quality cabernet and zinfandel, Billy Grant, the head of business development, pushes back against the narrative that Gen Z’s teetotaling ways are driving the industry toward collapse (opens in new tab). Wine, he said, has always had ups and downs — and it’s never been the province of the young. “Why are we so concerned that 25- to 30-year-olds aren’t drinking wine, when I don’t know anybody in this business who was drinking a lot of wine at 25 to 30?” Grant asked. “I wasn’t.”

In May, McPrice Myers unveiled a new tasting room (opens in new tab) with an airy, casual atmosphere designed to be as unintimidating as possible to people more accustomed to crushing White Claws. “You have to start these people off somewhere,” Grant said.

Nancy Ulloa of Ulloa Cellars (opens in new tab), a one-woman show producing white wines from lesser-known grapes, has another unconventional idea. Unlike stuffy, self-serious wineries that can be offputting to newbies, Ulloa says its wines include ingredients like “positive affirmations” and “goddess energy.”

She places strands of crystals on top of barrels and amphoras to infuse them with some of that positive energy during production. Many of her labels honor female deities or strong women.

Tastings are $22. An optional four-crystal pairing — no, you don’t get to keep the gems — is an auspiciously priced $11.11. The crystal-and-wine marketing has proved most popular with women, “but I also get a lot of men who are wine geeks,” Ulloa said. “It was really scary when I started to advertise that my wines were ‘a little witchy.’ It sounds woo-woo, but I’ve studied neuroplasticity, and I’m looking for evidence on how things change my brain and body.”

Drinks are served at The Alchemists’ Garden.

Drinks are served at The Alchemists’ Garden.

Alta Colina’s Tillman remains more of a traditionalist than some of his Paso peers. He believes new generations will be seduced by organic wine-making’s close relationship with the earth. Contrasting his wines with faddish canned cocktails, he noted that the latter are produced in an industrial park, and the cans come from a smelter. Meanwhile, he’s out there every day nurturing his vines, adjusting the micronutrients, and testing the density of bacteria and fungi in the soil. Yeasts native to his vineyard ferment the grapes.

The only fabricated element is the glass bottle. Then, he said, you put a cork in it, and the result is ethereal. “I think young people are going to catch on at some point,” he added. “This is the best liquid on the planet.”

Dining and Cooking