One of the largest olive oil production complexes known from the Roman world, located in the Kasserine region of western Tunisia, is now the focus of archaeological excavations. An international team from Tunisia, Spain, and Italy has spent several seasons studying the landscape around ancient Cillium, near the Algerian border. Their work is revealing a highly organized agricultural zone that once supplied vast quantities of olive oil to Rome.

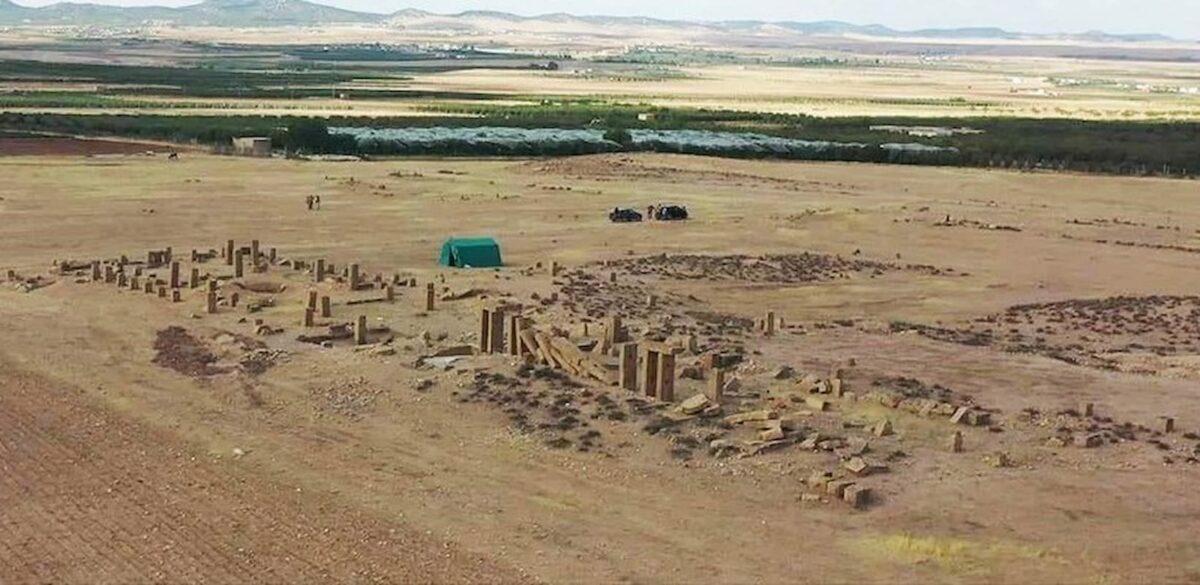

View of the excavations at Henchir el Begar. Credit: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

View of the excavations at Henchir el Begar. Credit: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

The most recent excavations have focused on two large olive-farming estates in the steppes of the Jebel Semmama massif. The terrain was exceptionally well suited for growing olives, despite the area’s temperature swings and limited rainfall. In the Roman era, North Africa became the Empire’s major oil-producing region, and Tunisia became Rome’s main supplier.

At the center of this research is Henchir el Begar, identified with the ancient Saltus Beguensis, a great rural estate documented by a 2nd-century inscription that authorizes a bimonthly market. The settlement covers about 33 hectares and is divided into two major sectors: Hr Begar 1 and Hr Begar 2, each equipped with pressing installations, water-collecting systems, and several cisterns. These complex installations form one of the most sophisticated agricultural production centers known in Roman Africa.

Location of Henchir el Begar. Credit: IPAR Project / Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

Location of Henchir el Begar. Credit: IPAR Project / Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

The first sector contains a monumental torcularium fitted with twelve beam presses, which makes it the largest-known Roman oil mill in Tunisia and the second-largest in the Empire. A second sector contains another industrial-scale installation with eight presses. Archaeological and stratigraphic evidence indicates that both complexes were active from the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, spanning a period marked by shifting political landscapes but enduring economic activity.

Torcularium at Henchir el Begar. Credit: IPAR Project / Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

Torcularium at Henchir el Begar. Credit: IPAR Project / Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

Surrounding the mills, researchers have identified a rural vicus where colonists and perhaps local families lived. The large number of millstones and grinding stones found scattered across the site indicates that this community produced oil and grain, demonstrating a mixed agricultural economy. Recent ground-penetrating radar surveys have also identified a dense cluster of houses and trackways beneath the surface, revealing a very different and much more structured rural environment than scholars had previously recognized for this frontier region.

The archaeological mission is the result of an international collaboration initiated in 2023 by Professor Samira Sehili (University of La Manouba, Tunisia; National Institute of Cultural Heritage of Tunisia) and Professor Fabiola Salcedo Garcés (Complutense University of Madrid, Spain). In 2025, the project expanded with the co-direction of Professor Luigi Sperti of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, supported by the institutional recognition of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. This partnership unites teams from Tunisia, Spain, and Italy and reinforces scientific cooperation across the Mediterranean while advancing research into the archaeology of production, particularly large-scale olive oil industries that played a defining role in ancient Mediterranean economies.

View of the excavations at Henchir el Begar. Credit: IPAR Project / Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

View of the excavations at Henchir el Begar. Credit: IPAR Project / Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia

In addition to the industrial remains, the team has uncovered finds dating from the Byzantine period into more recent times, including a decorated copper-and-brass bracelet, a limestone projectile, and architectural fragments such as a reused piece of a Roman press. Together, these discoveries attest to the longevity of the settlement and to the continuous recycling of materials over centuries.

More information: Università Ca’Foscari Venezia

Dining and Cooking