I’m

wearing my Paul Bocuse tie today, in honor of the great French chef, who died Jan.

20 at the age of 91.

Bocuse

himself gave me the tie, after I finished a meal at his restaurant, just

outside Lyon, in 1996. I protested that Wine

Spectator policies didn’t allow me to accept gifts. “Bof!” he said, tucking

it into my pocket.

I

was on a mission at the time: eat

in every Michelin three-star restaurant in France and report the

results for Wine Spectator. It was an

amazing (and grueling) three weeks of indulgence and education. Every

restaurant was different, each with its own personality. No restaurant had more

personality than Bocuse.

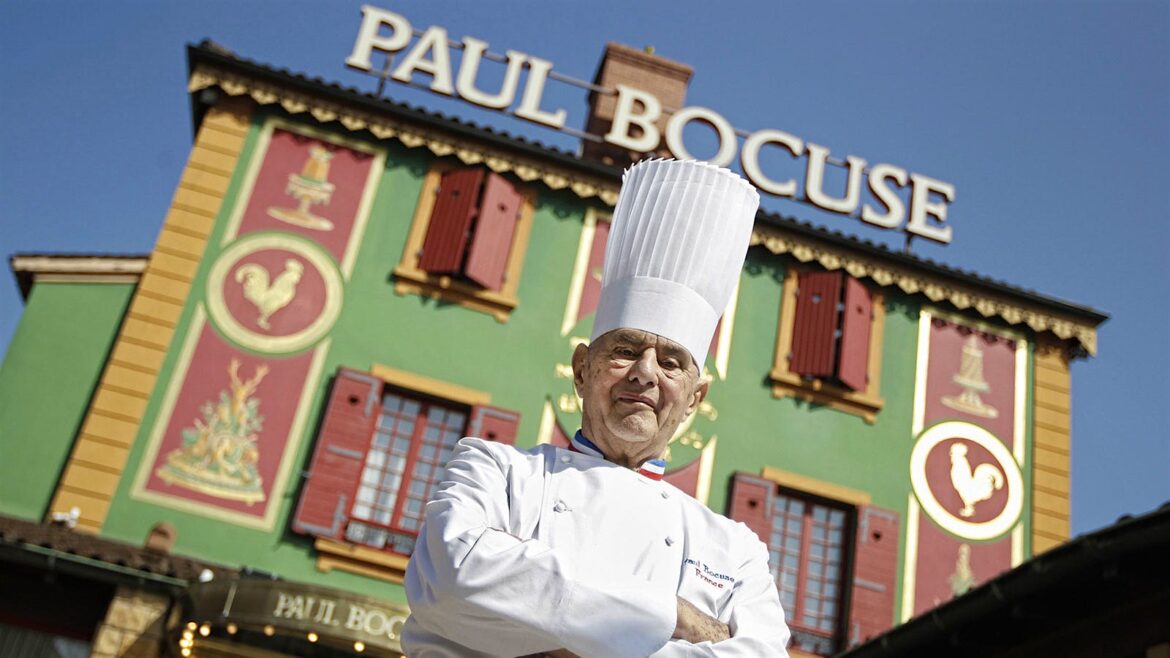

It

began with the building itself, a neon-lit, gaudily colored building with “Paul

Bocuse” in huge letters perched on the roof. The luxurious interior was

decorated with photos of the chef with the great figures of his time,

politicians and film stars. Bocuse had a big ego and irresistible energy;

there’s good reason, beyond his extraordinary culinary skills, that he became “the

most celebrated French chef of the postwar era,” according to his obituary in

the New York Times.

I

won’t recapitulate Bocuse’s extraordinary career; there are plenty of detailed

homages available, from colleagues and critics around the world. But that visit

from 1996 still echoes in my memory.

Alexandra de Toth

The Paul Bocuse tie

After

I enjoyed a brilliantly simple meal of truffle soup, filet of sole and roast

chicken, Bocuse sat down at the table. He was wearing the tallest toque I’ve

ever seen on a chef.

In

one hand, he held a black truffle the size of a baseball. In the other, an

Opinel pocket knife, the brand favored by farmers and hunters. He cut thick

slices of the raw truffle, dipped them in coarse salt, and munched on them like

celery.

“I

like them best this way,” Bocuse averred. Despite his menu’s luxury ingredients

and complex preparations, he preferred simple things. “French cuisine lost its

way,” he complained. “For a while, you couldn’t even identify what was on your

plate! Now we’re returning to the basics.”

Bocuse

believed in local products, traditional recipes and the glory of France. He

kept his prices lower than those of most of his colleagues, especially for

wine. (“I don’t have to charge any more, because most of this is already paid

off,” he half-joked.) For all of his global fame (and restaurants that

stretched from the U.S. to Japan), he was happiest at home, just outside Lyon,

where his family had been innkeepers and cooks for seven generations.

Bocuse

was nearly 70 at the time of my visit, and despite his bravado, his eyes seemed

sad. I asked about the future of his restaurant, and whether his son Jérôme

would one day take over. The “Lion of Lyon” looked around the room, filled with

happy customers and bustling staff. “I don’t know if it’s such a great

present,” he said.

Whether

or not Restaurant Paul Bocuse would be a welcome gift to his son (as of this

writing, the succession is still unclear), it was an immense gift to those who

were fortunate enough to experience a meal there. I never went back for another

visit. But I’m happy I still have the tie.

Dining and Cooking