The history of olive oil is also the history of our country, its markets, and its social transformations. Today, the price of extra virgin olive oil is at the center of heated debate, amid speculation, price fluctuations, and international dynamics.

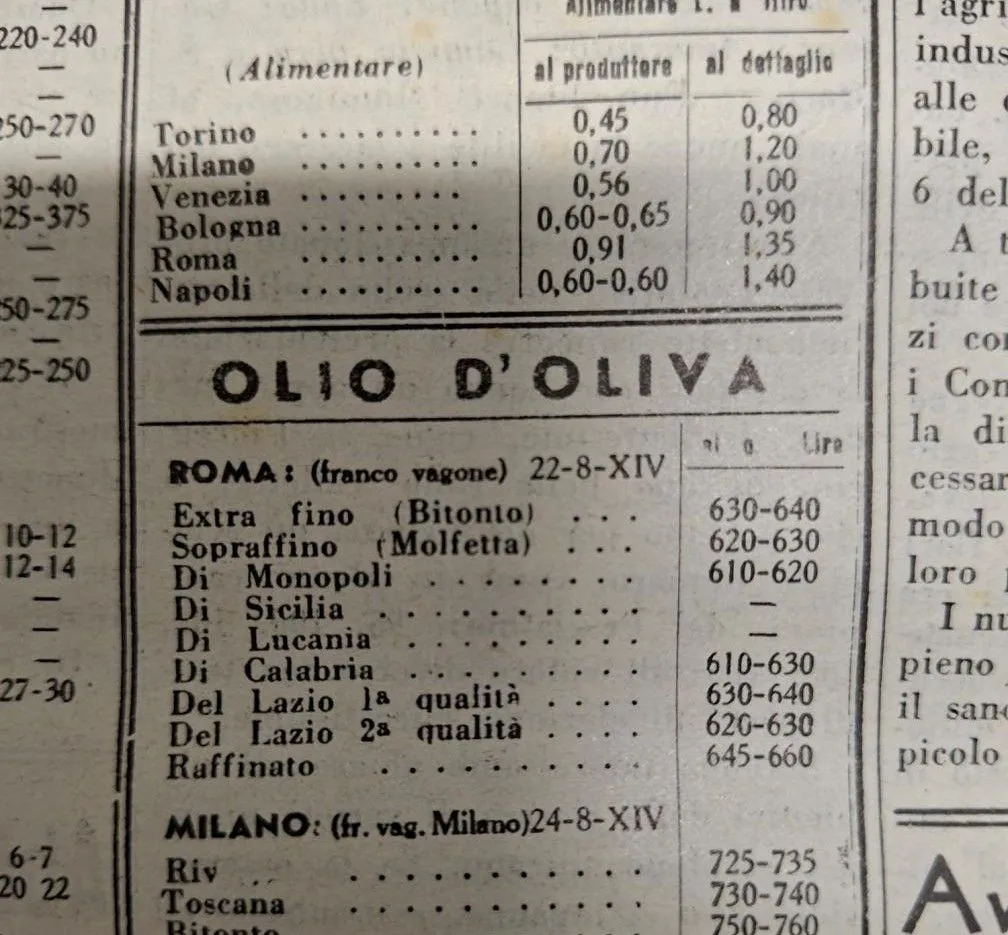

If we look back, a document from 1936 gives us a surprising image: How much was olive oil really worth almost ninety years ago? The dates reported in the price list, such as “22-8-XIV” and “24-8-XIV”, correspond to the fascist calendar, therefore to 22 and 24 August 1936, confirming the historical placement of the document.

Was olive oil more accessible back then than it is today, or was it a luxury for the average consumer?

Lost criteria: the categories of the 1936 price list

The turning point came with the Royal Decree-Law of 27 September 1936, n. 1986: the State accepted the already widespread mercurial practices and transformed them into official classifications, distinguishing between “superfine virgin”, “until” e “olive oil” obtained by refining or blending.

In this way the fragmentary and local denominations acquired national coherence.

Only decades later would the modern category of “extra virgin olive oil”: introduced by Law 13 November 1960, n. 1407, with the first quality requirements (maximum acidity at 1%), and perfected with chemical-physical and sensorial parameters by EEC Regulation 2568/91 and subsequent updates, up to Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/2104.

The economic sacrifice: more than a price, hours of work

The economic value of 1936, when compared to the incomes of the time, tells a different story than that which emerges from simple monetary conversions.“Extra fino (Bitonto)” quoted in Rome at 635 lire per litre It can be revalued with different methods: cumulative inflation leads to very high figures, even over one hundred euros per litre; monetary revaluation coefficients return lower values, around six or seven euros. The comparison with the average wages of the time, however, shows that a litre of quality oil could be equivalent to several hours of work, making it in fact a luxury itemMore than the absolute number, what matters is the relative economic sacrifice that the consumer had to make.

The gap between the supply chain yesterday and today

This gap between yesterday and today isn’t just monetary, but reflects the evolution of the entire supply chain. In the 1930s, production was manual and minimally mechanized, incomes were low, and producing quality oil required considerable effort. Today, by contrast, extra virgin olive oil is defined by strict parameters, with a maximum acidity of 0,8%, panel tests, and certifications that guarantee purity and traceability. Production costs have increased, but rising average incomes are making oil more accessible, transforming it from an elite commodity to an everyday staple.

The comparison between 1936 and today is not useful to establish whether oil cost more or less, but to understand how its relative value has changed. symbol of luxury and territorial identity, olive oil has become a regulated, certified and widespread food, while maintaining intact its role as an indicator of the country’s economic and agricultural health.

History in a bottle reminds us that every era assigns a different meaning to oil, but it is always central to Italian social and economic life.

Dining and Cooking