This is a guest blog post by Lucia Wolf, Italian Specialist and Reference Librarian in the European Reading Room

Reflections on the Tenth Week of Italian Cuisine in the World, November 2025

As the tenth anniversary of the Week of Italian Cuisine in the World concludes under the theme “Italian Cuisine: Health, Culture, and Innovation,” a fascinating paradox emerges: How does a cuisine rooted in profound regional fragmentation become a unified symbol of national identity? More intriguingly, how does this very fragmentation fuel innovation?

The timing carries special significance as Italian cuisine received UNESCO’s designation as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, with the final decision confirmed December 10, 2025. This recognition acknowledges Italian cuisine as a living cultural system—traditions, practices, and knowledge passed across generations. Yet the qualities making it worthy of this honor derive directly from a fragmented medieval past.

Medieval Roots: When Fragmentation Became Identity

To understand Italian cuisine’s distinctive character requires returning to the Middle Ages. French historian Pierre Toubert‘s groundbreaking work on Mediterranean feudalism analyzes incastellamento (encastellation)—the process by which medieval populations reorganized around fortified hilltop settlements. This created intense localization of power. Countless autonomous communes, city-states, and feudal territories developed their own economic, social, and political systems. What we now call “Italy” emerged from a constellation of distinct regional realities.

The Italian concept of campanilismo (from campanile, “bell tower”) enshrines this: one’s loyalty extends only as far as one can hear the village church bell. In cuisine, it manifests in passionate insistence that this valley’s prosciutto differs fundamentally from one produced twenty kilometers (or about 12 miles) away, that Parmigiano-Reggiano cannot exist outside specific provincial boundaries, or that only locally sourced San Marzano tomatoes make authentic Neapolitan pizza sauce. These are not merely marketing claims; they are deeply rooted local customs with medieval origins.

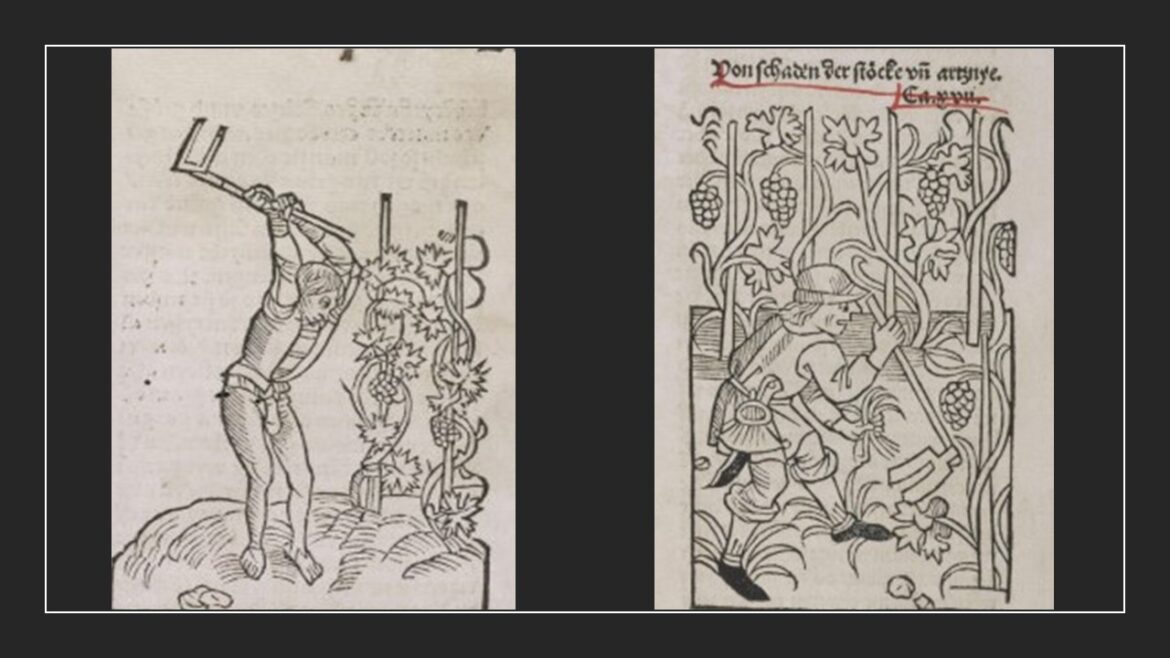

Even early manuscripts reveal this attention to place. Maestro Martino’s fifteenth-century Libro de arte coquinaria (Book of the Art of Cooking) emphasizes the origin and qualities of regional ingredients. That precision was not incidental: it was fundamental to how recipes were understood and valued.

Maestro Martino, Libro de arte coquinaria. [Northern Italy, between 1460 and 1480 ca.]. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The Unification Paradox

Maestro Martino, Libro de arte coquinaria. [Northern Italy, between 1460 and 1480 ca.]. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The Unification Paradox

Italy’s 1861 unification presented a peculiar challenge: How could a national cuisine emerge from regions separated for over a millennium, inhabited by people with different histories, mutually unintelligible dialects, and distinct cultural practices?

Pellegrino Artusi’s 1891 cookbook La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene (1895) (Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well) attempted to create national cuisine precisely when political unification threatened regional distinctions. His innovation? Rather than imposing a single standard, he catalogued regional diversity itself as Italian identity. The cookbook became a bestseller by celebrating difference, recognizing that these medieval micro-regional identities could coexist within a national framework.

Pellegrino Artusi, La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene. Florence, 1895. Rare Book and Special Collection Division. Photo by Lucia Wolf.

Pellegrino Artusi, La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene. Florence, 1895. Rare Book and Special Collection Division. Photo by Lucia Wolf.

Innovation Through Tradition

This year’s Week of Italian Cuisine in the World themes of “Health, Culture, and Innovation” might suggest breaking from tradition. Yet in the Italian context, innovation and tradition exist in productive tension, historically determined.

Consider the evolution from Martino’s manuscript tradition for elite courts to the democratization of Italian cookbooks in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Paradoxically, this “innovation” involved preserving and elevating peasant and regional traditions maintained across centuries. The sophisticated simplicity now associated with Italian cuisine with its emphasis on quality ingredients, minimal processing, respect for seasonal and local products represents the elevation of rural medieval and early modern practices.

The Slow Food movement, founded in Italy in 1986 as response to fast food culture, innovated by preserving traditional food production methods, local breeds, and regional specialties threatened by industrial agriculture. Similarly, Italian insistence on Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status for hundreds of products represents modern legal frameworks designed to protect traditional localized production.

UNESCO Recognition: A Living Heritage

Italy’s UNESCO nomination, titled “Italian Cuisine: Sustainability and Biocultural Diversity,” explicitly framed Italian food culture as living heritage—social practices, rituals, and gestures reflecting Italy’s cultural biodiversity. Significantly, the nomination came from both the Ministry of Culture and Ministry of Agriculture, acknowledging cuisine’s inseparable ties to land, agricultural practices, and social relationships.

With UNESCO’s 2025 recognition, Italian cuisine has become the first national cuisine recognized as a holistic cultural system, one where food culture is inseparable from social structure, historical experience, and relationship with place.

The designation provides tools for protecting not just products but the knowledge systems and cultural practices they embody. Italian products are among the world’s most imitated, and this recognition addresses that challenge while celebrating what makes Italian cuisine distinctive.

Health, Culture, Innovation Reconsidered

The themes of this year’s Week of Italian Cuisine in the World take on deeper meaning through this historical lens:

Health: The benefits of Italian cuisine, particularly its Mediterranean diet foundation, derive from localized agricultural systems developed over centuries. The emphasis on seasonal vegetables, legumes, whole grains, olive oil, and moderate amounts of meat and dairy reflects traditional practices now validated by contemporary nutrition research.

Culture: Italian food practices represent more than nutrition; they embody social relationships, family bonds, seasonal rhythms, and connections to place. The ritual of the family meal, the celebration of saints’ days with particular dishes, the marking of seasons through specific foods—these practices carried meaning in medieval communities and continue in Italian social life today.

Innovation: Perhaps the most profound innovation Italian cuisine offers is its model of cultural resilience. It demonstrates that modernity need not erase historical difference or enforce cultural homogenization, that local identity and global participation can coexist.

Stefano Asaro, Atlante slow food dei prodotti italiani. Cuneo, Piedmont: Slow food, 2012. Photo by Lucia Wolf.

Stefano Asaro, Atlante slow food dei prodotti italiani. Cuneo, Piedmont: Slow food, 2012. Photo by Lucia Wolf.

Amy Riolo, The ultimate Mediterranean Diet Cookbook: Harness the Power of the World’s Healthiest Diet to Live Better. Beverly, MA: Fair Winds Press, 2015. Photo by Lucia Wolf.

Amy Riolo, The ultimate Mediterranean Diet Cookbook: Harness the Power of the World’s Healthiest Diet to Live Better. Beverly, MA: Fair Winds Press, 2015. Photo by Lucia Wolf.

Fragments as Strength

With the UNESCO designation, we can consider Italian culinary history in relation to cultural heritage more broadly. The Library of Congress holds remarkable sources documenting this history—from medieval and Renaissance cookbooks to nineteenth-century domestic manuals to contemporary food writing. These materials reveal continuous attention to the specifics of place, ingredient, and method.

The fragmented inheritance, preserved through historical contingency and conscious choice, positions Italian cuisine as a model for cultural heritage that remains living and relevant in a globalizing world. The medieval past is not overcome but carried forward, its fragments not unified but celebrated as a more complex form of wholeness.

When you encounter Italian insistence on regional authenticity, remember: you’re not just tasting food. You’re experiencing history, geography, and resilient local identities that medieval towers and church bells once protected—now recognized as worthy of global heritage status.

Explore more related to Italian Cuisine at the Library

Dining and Cooking