Brazil’s largest olive grove is located in Rio Grande do Sul, with millions of trees, award-winning olive oils, and an agricultural venture that has transformed the national agribusiness sector.

For decades, the idea of producing olive oil on a significant scale in Brazil was seen almost as a joke in the agricultural sector. The consensus was simple: Good olive oil only came from the Mediterranean.Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Greece dominated the market, while Brazil was limited to importing practically everything it consumed. This scenario began to change in Rio Grande do Sul, where a group of producers decided to take a chance on something that seemed unlikely and ended up creating the largest continuous area of olive trees in the country.

Today, the state is home to the largest olive groves in Brazil, with millions of trees plantedgrowing production of award-winning extra virgin olive oils and a sector that has gone from experimental to becoming… a new frontier for national agribusiness.

The origin of the bet: similar climate, widespread disbelief.

The choice of Rio Grande do Sul was not random. Regions such as the Campanha Gaúcha and the Serra do Sudeste present cold winters, dry summers and well-drained soils, with characteristics similar to traditional olive growing areas in southern Europe.

— ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW —

See also other features

Standing up to 2,8 meters tall, weighing 156 kg, and laying eggs larger than bricks, the ostrich is the largest living bird in the world and a colossus that defies the logic of nature.

The lowest city in the world: built more than 250 meters below sea level, it has over 10.000 years of continuous human occupation and approximately 20 inhabitants.

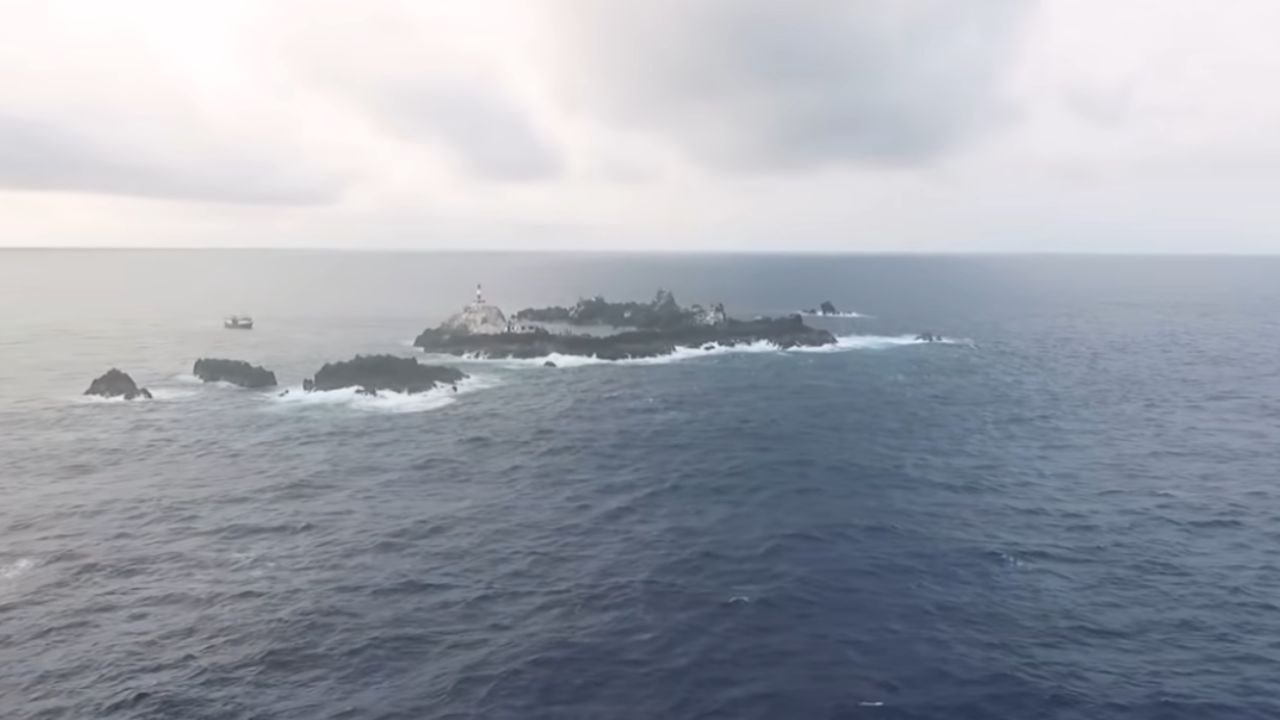

The Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago reveals the origin of the Earth’s mantle, constant tremors, incredible rescues like that of the Italian adrift, and Brazil’s struggle to maintain life in one of the most extreme places in the Atlantic.

Brazil surpasses war zones and enters the top 10 of global violence, being cited alongside Palestine, Myanmar, and Syria.

Even so, when the first projects emerged, they faced strong skepticismTechnicians doubted the seedlings’ adaptability, investors saw high risk, and many traditional farmers did not believe that Brazilian olive oil could compete in quality with imported oil.

It was precisely this lack of credibility that opened the door for unlikely investorsUrban entrepreneurs, rural producers of other crops, and even professionals with no background in agriculture are attracted by the combination of innovation, added value, and an expanding market.

Millions of trees and an unprecedented scale in the country.

Currently, Rio Grande do Sul is home to the largest olive plantation in Brazil, with areas that add up to millions of cultivated plants distributed across large properties. Some farms concentrate hundreds of thousands of trees in a single undertaking, something unthinkable in the country just over a decade ago.

These olive groves utilize internationally renowned varietiesThe varieties, such as Arbequina, Koroneiki, Picual, and Arbosana, were chosen after rigorous adaptation tests to the local climate. Planting follows modern standards, with technical spacing, controlled irrigation, and management designed for mechanized harvesting.

Brazilian olive oil that won an international award.

The definitive turning point came when the first olive oils from Rio Grande do Sul began to be evaluated outside of Brazil. In international competitions, labels produced in the state began to win awards. medals and recognitionsproving that quality was not exclusive to the Mediterranean.

These olive oils stood out for characteristics such as:

intense fruitiness

low acidity index

Extreme freshness, thanks to rapid extraction after harvesting.

Competitive sensory profile with imported products

The recognition changed the perception of the domestic market and made the Brazilian consumer begin to see the Brazilian olive oil as a premium productAnd not just out of curiosity.

Technology and precision from the field to industry.

Unlike traditional European olive groves, many projects in Rio Grande do Sul were conceived with [specific characteristics/preferences] from the start. modern industrial mindsetHarvesting is planned to occur at the exact point of ripeness, often using mechanized methods, reducing losses and ensuring standardization.

The olives go directly to own wine presses, installed on or near the farms. This detail is crucial, as the time between harvesting and extraction directly influences the quality of the olive oil. In some cases, this interval is only a few hours—something rare even in traditional olive oil-producing countries.

Rural tourism and olive oil as an experience.

In addition to production, the large olive groves of Rio Grande do Sul have begun to invest heavily in turismo ruralFarms opened their gates to visitors, offering:

guided tours of the olive groves

technical olive oil tastings

restaurants with wine-paired menus

specialty stores

Olive oil has ceased to be just an agricultural product and has become a cultural experience, attracting tourists from all over the country and helping to consolidate the sector’s identity.

The challenge that no one has yet completely overcome.

Despite its success, Brazilian olive growing still faces a central challenge: sufficient scale to reduce dependence on importsBrazil remains one of the world’s largest importers of olive oil, and while domestic production is growing, it still represents only a fraction of internal consumption.

Furthermore, the sector deals with climate risks, such as excessive rainfall during critical periods, unseasonal frosts, and variations in productivity between harvests. It’s a long-term game that requires continuous investment, agronomic research, and patience—virtues not always common in modern agribusiness.

A structural change in Brazilian agriculture.

Despite these obstacles, Brazil’s largest olive plantation has already played a historic role: It broke the dogma that the country could not produce high-quality olive oil.What began as a dubious gamble has turned into an organized, technologically advanced, and recognized production chain.

Rio Grande do Sul has ceased to be merely an indirect importer of olive oil and has begun to write its own history in the sector, showing that Brazil can indeed compete in markets traditionally dominated by centuries of European tradition.

Olive farming in Rio Grande do Sul proves that major transformations in agriculture don’t arise from consensus, but from bets that many consider improbable. Between skepticism, investment, and persistence, Brazilian olive oil has ceased to be an exception and has begun to become a brand identity.

And you, reader: Should Brazil invest even more in premium domestic olive oils or continue to rely primarily on imported products?

Dining and Cooking