South Dakota State University researcher Dr. Ananda Nanjundaswamy is developing natural, microbe-based pigments to replace synthetic food dyes like Red No. 3, which the FDA plans to ban by 2027. Working at the Dakota BioWorx POET Bioprocessing Center in Brookings, South Dakota, his team grows pigment-producing microbes using regional agricultural byproducts such as molasses and corn syrup. The process offers a safe, nutritional and sustainable alternative while creating new value for local farmers.

After successful 70-liter pilot batches, the project is advancing toward commercial production — positioning South Dakota as a leader in the growing market for natural colorants, which could disrupt the $1 billion U.S. synthetic dye industry.

South Dakota State University researcher Dr. Ananda Nanjundaswamy

/ Contributed

“The graduate students and undergraduate students who are working in this field on bioprocessing and fermentation technology for developing natural pigments are highly sought after, because that’s where the growth and development is going to happen in the next few years,” he said. “Workforce development is a big part of this endeavor.”

Nanjundaswamy said there are advantages of microbial production for carotenoids using agricultural co-products, offering precise control, shorter production times and significant economic value for various industries. Carotenoids are yellow, orange and red organic pigments produced naturally by plants and algae, and some bacteria, archaea and fungi.

“Some of these microorganisms that we grow in our lab produce beta carotene, so they are either red in color or yellow in color,” Nanjundaswamy said. “If you see a marigold plant, they come in different colors. Some of them are light yellowish, some orange, and the color on the flowers, in the petals, is due to a carotenoid called lutein.”

Lutein is an important component of eye health, as is beta carotene, a source of vitamin A.

Working at the Dakota BioWorx POET Bioprocessing Center in Brookings, South Dakota, Ananda Nanjundaswamy’s team grows pigment-producing microbes using regional agricultural byproducts such as molasses and corn syrup.

/ Courtesy South Dakota State University

Waiting months for plants to produce carotenoids is inefficient, and environmental factors can affect yield. Growing algae also requires costly photobioreactors. To overcome these challenges, Nanjundaswamy’s lab uses microorganisms like yeast and fungi.

“The advantage of these microorganisms is that they can be grown in a bioreactor,” he said. “Bioreactors are the reactors in which we have ultimate control over their growth, and also these microorganisms, the fungi and yeast, they can grow and produce within five days or six days. So using plants would take about three months or two months, but we can reduce the time to three, four or five days, which is a big savings.”

Carotenoids not only provide color but also offer health benefits, including eye protection and antioxidant properties. Beyond food and drug applications, Nanjundaswamy sees potential in animal feed, where 90–98% of color additives are synthetic.

“We would like to replace those synthetic colors also with the natural colors, because ultimately animal products will land on our plates, whether it is milk, whether it is an egg, whether it is salmon,” he said.

Animals may not care about color, but humans do.

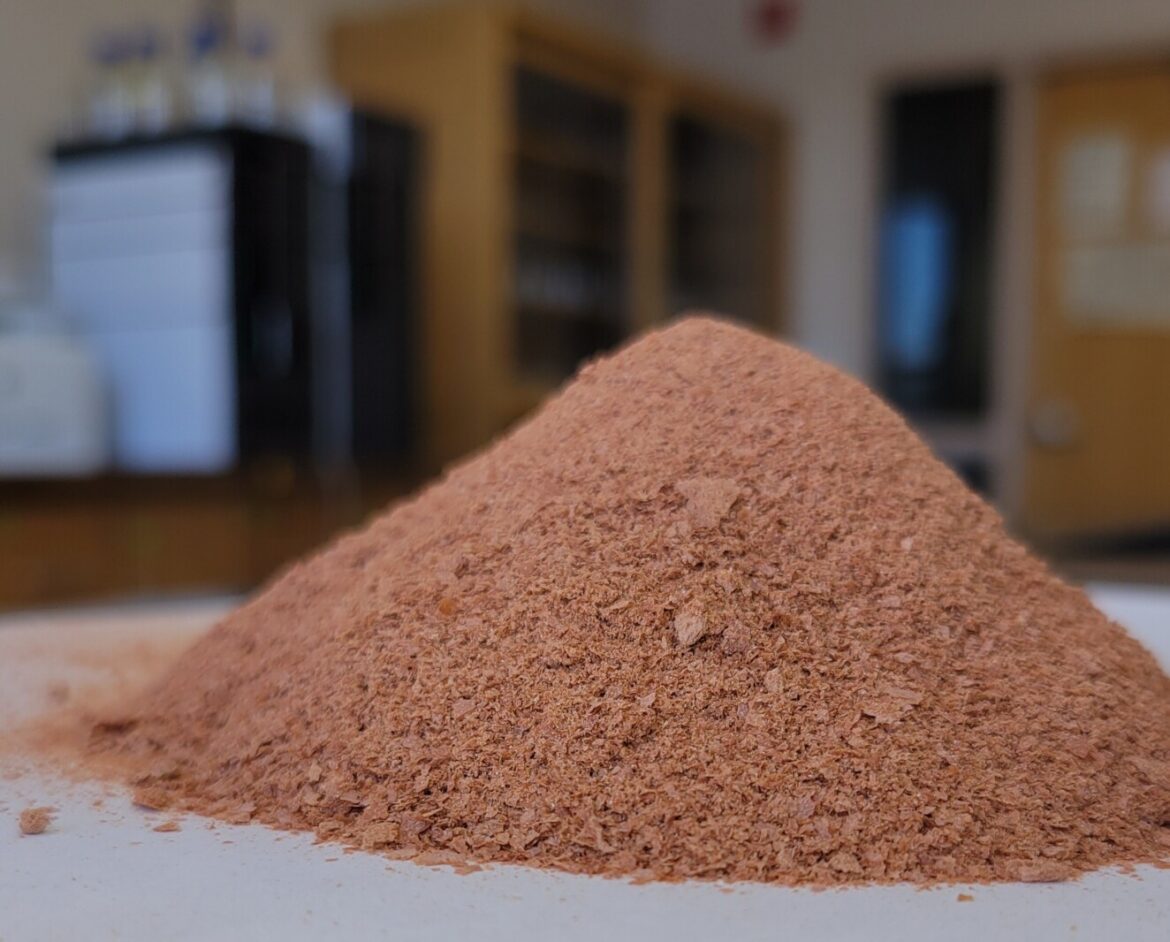

The SDSU research team is producing natural replacements for synthetic food dyes using microorganisms.

“If you go to a feed store, you would rather pick up a color. We pick up a feed which is really bright in color rather than an insipid color thing. It is very natural for people to prefer colored meat. It is unfortunate that we use more synthetic colors in the United States than anywhere in the world. Because of the preference, we relate color with quality and, unfortunately, those colors are not having any benefit. So how about replacing them with natural colors, which have biological activities also? That it is a win-win for everyone,” he said.

He noted that salmon’s orange hue comes from a carotenoid called astaxanthin, which benefits skin and eye health. Synthetic astaxanthin is less effective, and no commercial natural version exists for salmon feed — a gap his research aims to fill.

“Also, the natural colors, which have antioxidant properties, will finally help the animal and ultimately, the animal product will help us. For example, beta carotene. If you feed it to cattle, the milk produced by such animals will have a better shelf life quality,” Nanjundaswamy said.

His team studies microbes to determine how to grow them at scale for pigment extraction or direct use as natural colorants.

“My lab works on producing these colors using microorganisms, and the majority of these microorganisms that my lab works on are non-pathogenic. That means they don’t cause any health-related diseases or things like that. They’re all isolated from the natural environment,” he said.

From an economic standpoint, the Upper Midwest produces a lot of agricultural products and byproducts. One of those byproducts used in his lab to grow the microorganisms is sugar beet molasses. Traditionally, sugar beet molasses is used as a commodity product in animal feed. It’s rich in carbohydrates and rich in minerals.

“When we are growing them in sugar beet molasses, we are converting a very low-value sugar beet into a high-value natural color. And the natural color can go back to the animal feed industry, which is going to cost, you know, several thousands or even millions of dollars in value. And in fact, the animal feed industry is really looking forward to these natural colors,” he said.

When looking at human-grade foods and pharmaceuticals, where colorants are required, it runs into the billions of dollars.

“We are essentially taking a product which is very low value, like molasses, and growing these microorganisms and producing the colors and then making it available to a high-end market,” Nanjundaswamy said. “Now, in the whole value addition process … we are basically value adding to a low-value product and creating a high-value product. And in this value chain, farmers are going to get benefits.”

He envisions a sugar beet processing plant having a carotenoid or pigment production facility next door, which can then supply those natural food colors to food ingredient companies or pharmaceutical companies.

“The long-term goal is to enhance the rural economy by utilizing these agricultural co-products,” he said.

Corn syrup, a high-calorie sweetener, is a co-product obtained during corn ethanol processing – an ingredient that can have negative side effects to humans if consumed in large quantities, the FDA says. High fructose corn syrup is shown to have negative effects on the body, including weight gain, spikes in insulin levels and increased production of triglycerides, which can increase the risk of heart disease.

“We take that high fructose corn syrup and we try to grow these microorganisms in that and then convert the high fructose corn syrup into a natural pigment-produced yeast biomass, which can be used as an animal feed ingredient, especially for a natural tolerance of animal feed as well as for a food ingredient. So what we consider as something very unhealthy, you can take it and make it a very healthy natural product through microbial fermentation or microbial transformation,” he explained.

Nanjundaswamy’s research team is also exploring products that can be made from the enriched compounds. For example, they’re testing how the pigments could be used in personal care items like lipstick or other cosmetics that typically rely on synthetic colors.

The more products that can be developed from the carotenoid enrichment, the more benefits consumers could see in the future.

Dining and Cooking