Laura Maioglio — the force of taste, tradition and meticulous hospitality behind Barbetta, the storied Italian landmark on W46th Street — has died, the restaurant announced Wednesday evening.

Laura Maioglio, the longtime owner of Barbetta on Restaurant Row. Photo montage Denice Flores Almendares/Barbetta Archive

Laura Maioglio, the longtime owner of Barbetta on Restaurant Row. Photo montage Denice Flores Almendares/Barbetta Archive

“It is with deep sadness that we share the passing of Ms. Laura Maioglio, the heart and soul of Barbetta,” the Barbetta family wrote in a statement, calling her guidance “an unwavering commitment to excellence” over more than six decades.

For generations of New Yorkers, Barbetta has been more than a pre-theater reservation. It’s been a time capsule: connected brownstones, a candlelit dining room crowned by old-world chandeliers and a garden that feels like it shouldn’t exist in the middle of Midtown. That atmosphere — equal parts Piedmont and Manhattan — was Maioglio’s life’s work.

Born and raised in New York, Maioglio attended the Brearley School and later graduated magna cum laude from Bryn Mawr College with a degree in art history. Her family roots reached back to Piedmont, where she spent long stretches throughout her life, including a year studying at the University of Florence. Those extended stays helped shape the particular Barbetta she built: a restaurant anchored in northern Italian cuisine, confident in its regional identity and deeply serious about ingredients, wine and craft.

Barbetta was founded in 1906 by her father, Sebastiano Maioglio, who immigrated from Piedmont and opened the original restaurant on West 39th Street near the old Metropolitan Opera House. In 1925, he bought the four brownstones on W46th Street that remain Barbetta’s home.

Maioglio stepped into leadership in 1962, and quickly made the boldest change in the restaurant’s history: she closed and remade it. In a Manhattan Sideways interview, she recalled learning that her father had sold Barbetta — and intervening, emotionally and directly, to keep it in the family. She then set about transforming the space in the style of 18th-century Piedmont, a decision that reshaped Barbetta’s identity for decades to come.

She didn’t simply decorate. She curated.

Maioglio hunted for pieces that felt true — objects with their own history — and she was famously patient in pursuit of them. She once described negotiating for two years to obtain the chandelier that became a centerpiece of the dining room, originally from a royal family home and later shipped over and reassembled in New York.

PHOTO ESSAY: Behind the scenes at Barbetta. Photos: Denice Flores Almendares

The attention to detail extended everywhere: reproductions were commissioned only when authentic pieces weren’t possible in quantity, and the room’s sense of European grandeur became part of what diners came for, as much as the food.

Maioglio’s Barbetta, as W42ST reported in 2024, stayed rooted in her father’s founding philosophy — authentic Italian cooking, made accessible — even as she refined it. She “changed it a lot in its details, not in its philosophy,” she told W42ST, explaining that she worked to make the restaurant even more authentically Piedmontese.

That Piedmont identity wasn’t just branding. It was the kitchen, too: handmade pastas, regional techniques, and dishes tied to place. Barbetta’s menus became a form of living archive — with items marked by the year they first appeared, and Piedmont specialties highlighted.

Maioglio also helped push New York’s Italian dining scene forward by insisting on ingredients that, at the time, were still rare in the United States. In the Sideways interview, she recalled Barbetta being the first restaurant in the country to serve truffles — at a time when they simply weren’t available here commercially. The workaround was as old-school as it gets: someone would fly in with a box of truffles from Milan, then hand-deliver them straight to the restaurant.

And in one of those Barbetta stories that sounds like a joke until you remember it’s Barbetta, Maioglio said the restaurant even had truffle hounds — and staged a demonstration with the dogs not just in the garden, but at Carnegie Hall.

Barbetta’s Laura Maioglio and the Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer at a press conference on Restaurant Row in May 2017. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Barbetta’s Laura Maioglio and the Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer at a press conference on Restaurant Row in May 2017. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Barbetta was also, she noted, among the earliest adopters of espresso culture in America: Maioglio said her father imported an espresso machine as far back as 1911.

To the dining room regulars, though, Maioglio wasn’t just the keeper of antiques and culinary milestones. She was the presence. The woman who noticed. The one who could tell you what was wrong with a dish, and also tell you the history of the room you were sitting in.

“She’s a perfectionist,” longtime staff member Eduardo told Manhattan Sideways, describing how everything — down to the lamb and the flowers — had to be “a certain way.”

Maioglio was also a storyteller with impeccable timing, especially when it came to the unlikely collision of Barbetta’s old-world elegance and New York’s pop-culture chaos.

She recalled her mother — glamorous, devoted to the public-facing rhythm of the place — mistakenly worrying that a scruffy-looking guest might not afford the restaurant. The guest was Mick Jagger.

When the Rolling Stones later learned her mother had died, Maioglio said they went out, bought flowers, and returned to place the bouquet in front of her photo.

Barbetta’s guest list was famously eclectic — a steady mix of theatergoers and locals, with the occasional boldface name drifting through the rooms. Maioglio would mention Andy Warhol as one of the restaurant’s regulars, long before “celebrity spotting” was a Midtown sport.

Maioglio’s husband, Dr. Günter Blobel, was a scientist at Rockefeller University who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1999. Maioglio frequently kept the restaurant and her private life distinct — but Barbetta, as always, managed to sit at the intersection of art, culture and the city’s famously mixed dinner tables.

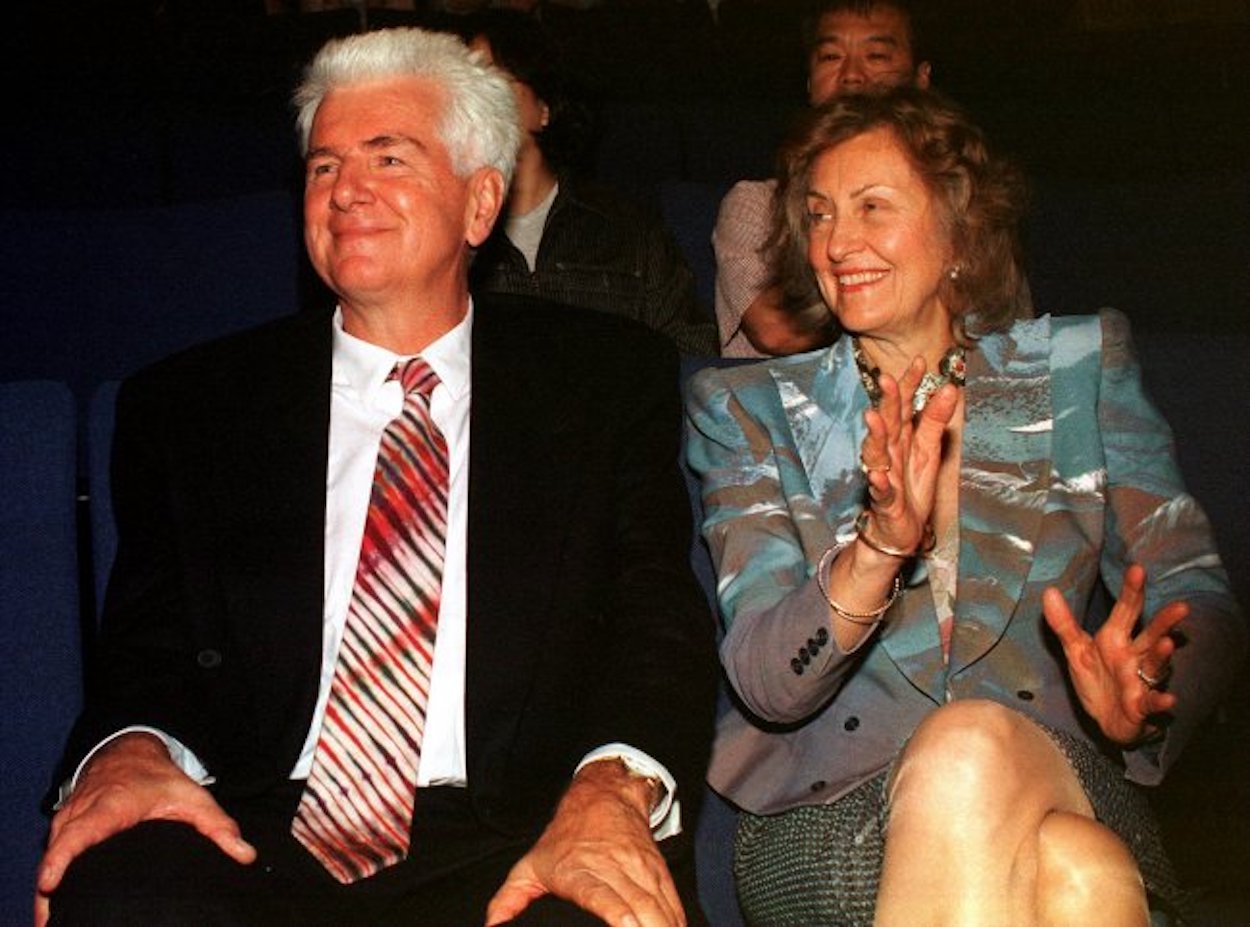

Nobel prize winner Dr Günter Blobe and wife Laura Maioglio. Photo: Barbetta Archive

Nobel prize winner Dr Günter Blobe and wife Laura Maioglio. Photo: Barbetta Archive

In its statement announcing her death, Barbetta said the restaurant will remain open “for the time being,” continuing the traditions Maioglio cherished, and encouraged patrons to keep gathering there — “to enjoy the food, wine and warmth that have always defined this house.”

Maioglio, the statement added, often referred to the staff as her “dream team,” and said they hoped to carry her legacy forward.

Barbetta wasn’t merely “old.” Under Laura Maioglio, it remained alive — not as nostalgia, but as a living room for the city. And as she once put it, some places can’t truly be explained: “I think that you have to simply experience it to see it.”

Dining and Cooking