EAGEN, Minn. — At the dawn of the jet age and commercial flights in the early 20th century, there were no first-class seats.

And while flying in the 1930s was a luxury most could not afford, all on-board stomachs were fed the same, with butter-roasted chicken, mashed potatoes, freshly cooked golden French toast, sushi, sashimi and even caviar.

“Only one kind of airline travel existed in the 1930s and 1940s — first class,”

the Post-Bulletin reported.

The first in-flight meal was served up in 1929, on a Golden Ray Service flight from Paris to London.

“Trained stewards were recruited from (the) best London hotels to serve elegant sandwiches and cakes to passengers,” reported The Post-Bulletin of Rochester, Minnesota.

The first in-flight meal in America was served in 1929 on Transcontinental Air Transport, the forerunner of TWA. Most meals consisted of a sandwich and fruit, but the nation’s first noticeable fine dining was served in 1941 to 21 well-to-do passengers aboard a DC-3 about 8,000 feet above the Earth.

”It was a meal fit for royalty,” the Post-Bulletin reported. The silver was sterling; the napkins, damask; the service, impeccable.

As competition between burgeoning airlines increased, efforts to improve the cuisine followed suit.

“Airlines began to spend time and effort to keep passengers — and their stomachs — happy,” the Post-Bulletin reported in 1988.

Airline executives hired dietitians and food consultants, who offered advice on what foods created air sickness and lingering odors. Broccoli and fish were nixed off most menus.

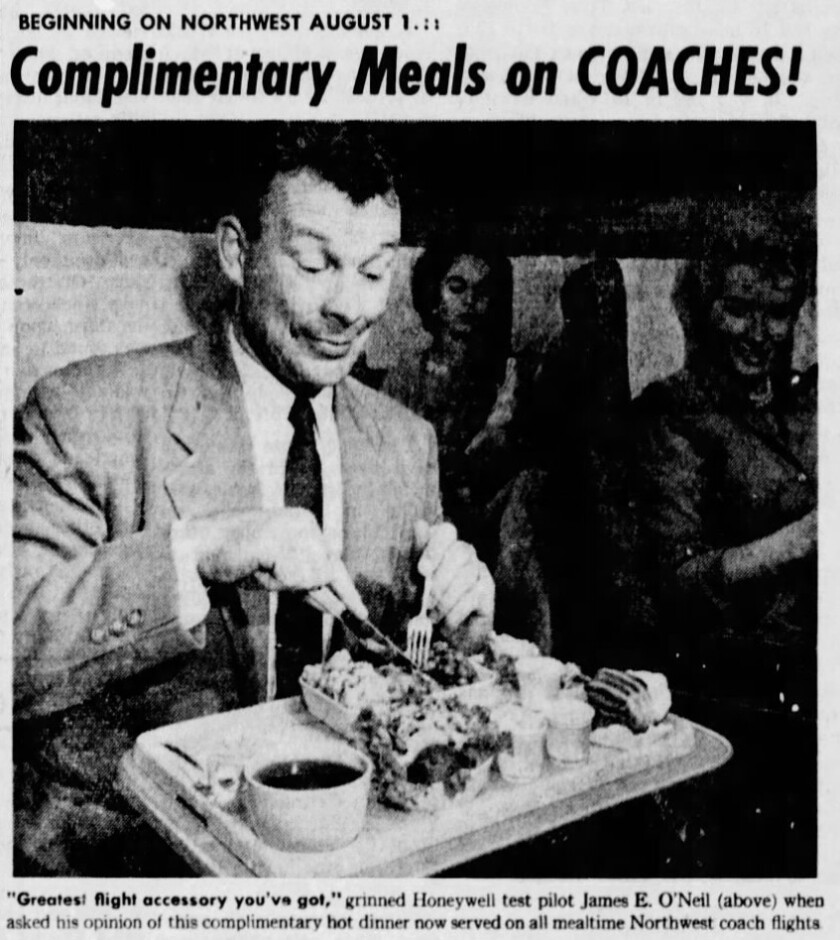

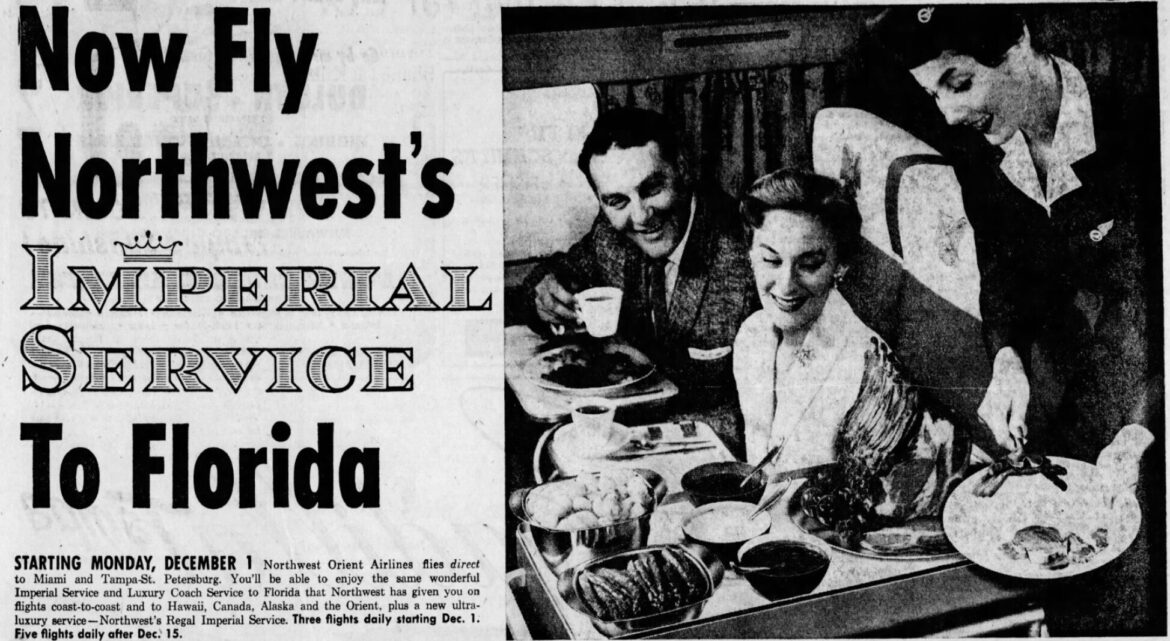

Northwest Orient passenger, James O’Neil enjoys a hot dinner aboard a flight in 1959.

Contributed / Minneapolis Star via Newspapers.com

Cheaper tourist class tickets

were not introduced until 1948, and economy class began six years later.

Scandinavian Airlines System, or SAS, went on the food offensive in 1952 by starting the “great sandwich wars,”

Time Magazine reported in2015.

SAS serviced open-faced sandwiches to the new tourist class, according to Medium Magazine.

“Beautiful, lavish, open-faced sandwiches. A culinary feast of sandwiches laden with delicious ingredients, freshly carved meats and cheese and anything else a traveler could wish.” Medium Magazine reported, adding that competitors argued SAS served three-course dinners to coach class passengers, degrading the purpose of more expensive first-class tickets.

Imperial Airways, countered, offering five-course luncheons on its 220-mile flight across the English Channel. Bedtime snacks were offered before sleep, and “piping hot breakfasts of stewed fruit, eggs, ham or bacon and coffee” were available upon waking,

Alitalia, now the state-owned airline, ITA Airways, dove into the foodfight by skipping sandwiches and going straight to an Italian restaurant in the air.

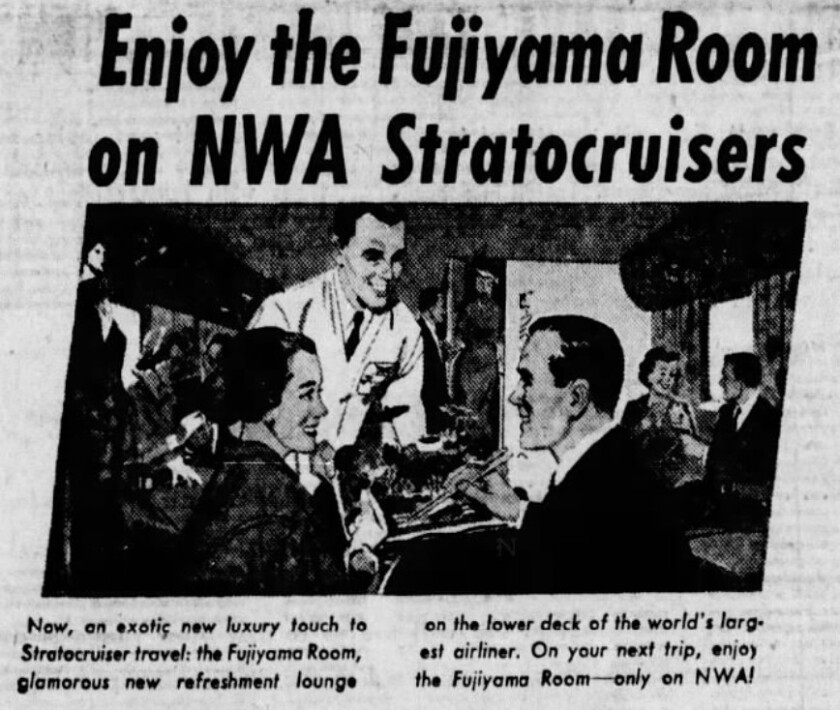

With the 1955 implementation of the “Fujiyama Room,” a flying tiki lounge offering American-styled Japanese food, Northwest Orient, later known as Northwest Airlines (it merged with Delta in 2010), quickly became a brand name synonymous with high class,

the Star Tribune reported in 1992

.

“On the NWA Stratocruiser, you have the comfort of the world’s largest airliner, with room to roam its double decks. Enjoy the Fujiyama Room, a glamorous new refreshment lounge on the lower deck. Beverage service. And come hungry. Even weight-watchers weaken at the sight of the Fujiyama tray, a mere prelude to the choicest dinners served aloft,”

a Northwest Orient advertisement announced in 1956 in the Minneapolis Star.

Advertisement for Northwest Orient’s Fujiyama Room, or tiki bar, in 1956.

Contributed / Minneapolis Star via Newspapers.com

Northwest Orient, originally headquartered in Eagen, also began serving complimentary hot meals at appropriate times of the day on all their flights to everyone in coach seating,

according to the Minneapolis Star.

Although there was now a growing distinction between coach and first class, Northwest executives tried catering to the masses.

“Luxury at low coach fares,” a headline in the Star Tribune announced in 1958. “It’s high flying for low budgets.”

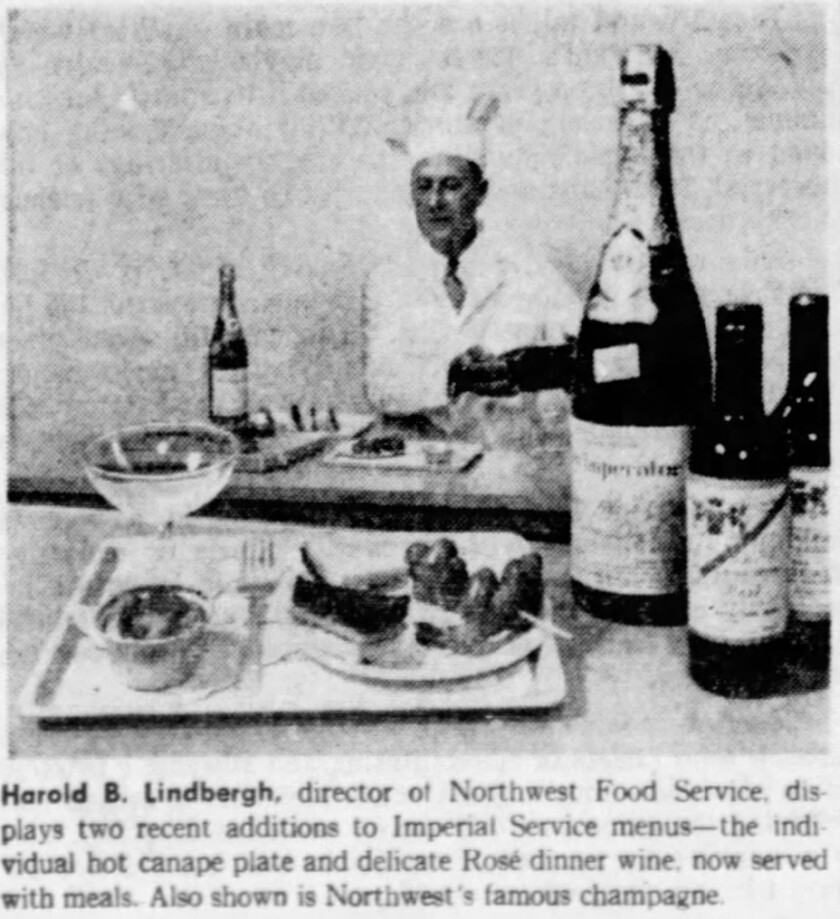

Complimentary meals in 1958 included free beverages, alcohol, prime ribs of beef, Cornish hens, French pastries, all from Northwest’s Regal Imperial Service. For $3 more than a first-class ticket, a passenger could also use an air-to-ground telephone to talk to friends at 20,000 feet, according to the Minneapolis Star.

Opposition, like Concorde, operated by British Airways and Air France, tried raising the bar by offering even more luxury in the 1970s.

“Passengers on the Concorde famously drank Champagne while indulging in caviar,”

Reader’s Digest reported.

American Airlines President Bob Crandall at upper left in an article published by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 1997.

Contributed / Fort Worth Star-Telegram via Newspapers.com

Federal deregulation in the 1970s led to fierce competition between airlines, lowering ticket prices and raising food costs. The decade welcomed Southwest Airlines, who in 1971 kicked off the tradition of serving peanuts as a mid-flight snack, eventually incorporating the legume into a slogan: “fly for peanuts.”

United Airlines ramped up its kitchen staff to 3,000 employees. In-flight menus —planned a year in advance — rotated every two weeks.

For a time, United Airlines got personal, introducing in-flight hot cocoa, linens, flowers and specialized dishes, like an Oktoberfest menu in the 1980s.

Rising food costs began worrying airline executives, however. In 1987, Bob Crandall, CEO of American Airlines, noticed something strange while on a flight: nobody was eating their olives.

He cut out one olive per salad per passenger. “A tiny garnish would never be missed, the reasoning went, and savings amounted to at least $40,000 a year,”

NBC News reported in 2003.

Called a notorious move by many newspapers, the cost-cutting measure sent a tidal wave of changes throughout the airline industry, the Forum of Fargo-Moorhead reported in 2005. With only about 5% of operating costs going toward food, airline executives still expected savings.

And it worked, for a while.

Delta Airlines saved $1.4 million a year by eliminating a decorative leaf lettuce under vegetables.

US Air saved $1 million a year by pouring an eight-ounce cup of soda rather than giving passengers an entire can.

Continental Airlines, which in 1999 spent about $250 million a year on in-flight food service, joined other airlines in hiring notable chefs to redesign menus at 35,000 feet in the air.

American Airlines, which served about 169,000 meals per day, started slicing melons instead of cubing them, saving about $16 million in 1993.

A decade after the Oktoberfest menus, United Airlines switched from hot to cold breakfasts and snacks, and eliminated all food in economy class on overnight flights. Passengers who could afford better seats, however, didn’t see a change.

“With fares virtually identical on most routes, airlines try to distinguish themselves with fancy perks. Most are found behind the curtain in first class, an Everett, Washington, newspaper reported in 1993.

Northwest Orient announces non-stop flights to American east and west coasts in 1958.

Contributed / Star Tribune via Newspapers.com

By 1995, airline food — now a subject of bad jokes — underwent a makeover as many airlines started offering everything from McDonald’s cheeseburgers to Starbucks coffee.

Blimpie sandwiches began appearing on Delta Airlines. Continental Airlines began featuring Subway sandwiches.

United Airlines snagged McDonald’s meals for kids, and Chicago-style stuffed pizzas made by Edwardo’s Natural Pizza Restaurants to first-class passengers.

“Branded foods are perceived as having more value and being of better quality,” Larry DeShon, director of catering for United, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1995.

The business agreements were a boon to restaurants, and airlines hoped the change would cut costs as well as increase passenger traffic.

“People like to be served branded food,” Todd Clay, a Delta spokesperson, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “They are familiar with the taste. No matter where they go in the country, Blimpie always tastes the same.”

Except at 30,000 feet, taste changes.

“Loud airplane noise literally changes your sense of taste, due to a phenomenon called psychophysics,” Reader’s Digest reported. “Noise didn’t affect salty, sour or bitter tastes. But sweetness got significantly dulled, while umami (the savory flavor) actually became stronger, especially at higher concentrations.”

More salt and sugar and less savory umami such as MSG and oyster sauce is needed to achieve that familiar taste,

according to RadioLab,

a Peabody Award-winning public radio program produced by WNYC Studios.

“It’s why tomato juice tastes better on a plane,”

Reader’s Digest reported in 2025.

Northwest Orient food services for their Imperial Service menu featured in the Minneapolis Star in 1959.

Contributed / Minneapolis Star via Newspapers.com

In 2001, after the 911 attacks, the food dogfight ended with a whimper as many airlines began facing bankruptcy. Northwest Airlines — once considered the epitome of glamour during the high-altitude food battles — was the first to end free meals, and eventually merged with Delta.

Cost cutting measures deepened for the airlines that survived, raising an outcry from passengers.

“What next?” An olive garnish (oh, for the salad days of yore) seems inconsequential in these days when flying has been cut to the bare bones,” the Forum of Fargo-Moorhead reported. “Domestic carriers have already eliminated magazines, pillows and blankets. Now they’re trying to starve us.”

Today, Delta offers complimentary cookies or Cheez-Its. A snack box for flights over 900 miles costs $10, according to the company’s website.

United advertised on its website that snacks are available to purchase on flights over 500 miles, while free snacks for economy seating are available on flights over 300 miles.

Southwest Airlines offers complimentary non-alcoholic drinks as well as small bags of pretzels and cookies are available on select flights over 251 miles. Peanuts, however, are no longer on the menu.

Dining and Cooking