Stephanie White had $10 for groceries for an entire month. She bought a bag of rice, two pumpkins and ten cans of tuna. That was it.

White, 32, is a PhD student at UMass Boston who works 60 hours per week as a research assistant and cashier. Her income still falls $65 short of her monthly expenses—forcing her to drive for DoorDash to break even.

White isn’t alone. According to the Massachusetts Hunger-Free Campus Coalition, 44% of public university and community college students in Massachusetts face food insecurity. The problem predates the pandemic: A 2019 study at Bunker Hill Community College found 56% of students were moderately food insecure, according to Edible Boston.

Many students like White rely on SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, to survive.

Before starting her PhD, White worked as a social worker helping people access SNAP and other benefits. While in that role, she made a startling realization: “Most of my clients were at a higher professional and income level than I was,” she said.

She applied for SNAP and qualified. But the approval process took a month—leaving her with almost no money for food during the wait.

For the past two years, White has relied on SNAP to supplement her budget. But the benefits are constantly threatened. Every six months, she receives a cancellation notice due to administrative technicalities.

In November, White received another notice saying that her SNAP benefits would be cancelled due to her being an “able-bodied adult without dependents.”

White is deaf and uses mobility aids. Yet the system classifies her as “able-bodied” and forces her to reapply every six months with the same documentation. “It is extremely difficult to stay on SNAP,” she said.

When White needed $340 to replace her arm crutches, the expense meant even tighter food budgets. During her undergraduate years, she was on the minimal meal plan. “I only had, I think, one meal a day on weekdays and like occasionally two,” she said.

Now, pursuing her doctorate a decade later, the situation hasn’t improved. “I’m struggling in every way to make ends meet,” she said.

For many students, SNAP benefits could help, but accessing them is complicated.

Federal eligibility rules require students to be enrolled at least half-time and meet one of the following additional criteria: working at least 20 hours per week, participating in federal work-study, caring for a child under age 6, or others. These restrictions mean that even students who are struggling to afford food may not qualify, or don’t realize they’re eligible.

“That will only make it more challenging and potentially deter more people from signing up for SNAP,” said Chelsea Alexander, coordinator of the DISH Food Pantry at Bunker Hill Community College.

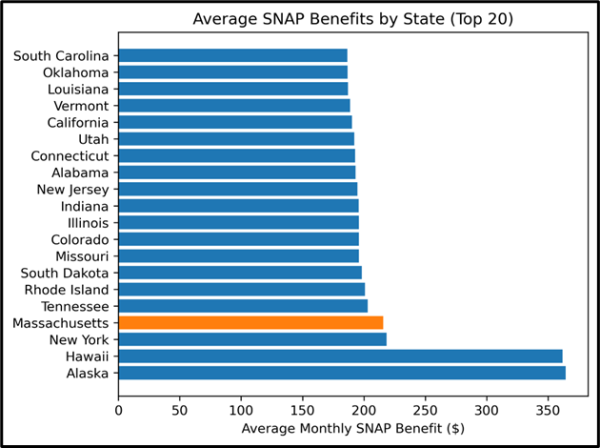

Source: SmartAsset, 2024. Massachusetts ranks fourth nationally in average SNAP benefits.

Source: SmartAsset, 2024. Massachusetts ranks fourth nationally in average SNAP benefits.

Visualization by Darshan Balaji

And for those who navigate the bureaucracy successfully, the benefits rarely stretch far enough. On average in Massachusetts, an individual receives $215.64 through SNAP benefits monthly, which is fourth highest in the country, according to SmartAsset. That monthly total amounts to only about $7.20 per day.

Even if SNAP benefits are meant to supplement people’s food budgets, the benefits end up being the primary food budget for most people.

“SNAP cannot fill the gap for everyone,” said Kate Adams, senior public policy manager at the Greater Boston Food Bank. “Many people are working hard and on SNAP benefits, but are still not able to keep food on the table for their families.”

For White and students like her, food pantries have become the one reliable source.

Campus food pantries across Boston reveal the scale of student need. At Bunker Hill Community College, the DISH Food Pantry distributed 95,659 pounds of food in 2024 and currently serves more than 750 students on a regular basis. The Rox Box at Roxbury Community College served nearly 600 students in November 2025 alone.

The Rox Box, serves students that are part of Roxbury Community College, supported by local partners.

The Rox Box, serves students that are part of Roxbury Community College, supported by local partners.

Kiara Rosario, 37, coordinator of the Rox Box food pantry, wasn’t always on the other side of the counter. When she was a student struggling to survive, she says her ex-partner stole her EBT card during their separation. It was the height of the COVID pandemic, and receiving a replacement card took weeks.

“It was very hard for me to be able to get food for my daughter and myself during that time,” she said. A single mother of a daughter with autism, she nearly dropped out.

Rosario survived and now helps other students as a Rox Box Student Trustee. But her experience revealed a fundamental vulnerability: students who depend on SNAP are one crisis away from catastrophe.

That crisis arrived last fall when the federal government shut down for 43 days, disrupting SNAP benefits for 1.1 million Massachusetts residents.

During the November shutdown, Rosario watched the anxiety spread. “Students were nervous about not having food,” she said. Even under normal circumstances, students face impossible questions. “When the cafeteria closes, what can they do to eat?” she asked.

The stigma compounds the challenge. Students arrive at the Rox Box “sometimes embarrassed due to the stigma of needing to use the food pantry,” Rosario observed. She tries to create a welcoming atmosphere—wearing bright colors, playing music. Her guiding principle is simple: “We don’t say no,” she said.

During the federal government shutdown, that principle was tested like never before. At the onset of the delay, the Greater Boston Food Bank had recorded a 25% to 30% increase in demand across its 600 partner food pantries. As October came to a close, “We saw a big surge from people who were scared that they wouldn’t get the benefits they were owed,” said Kate Adams, senior public policy manager at the Greater Boston Food Bank.

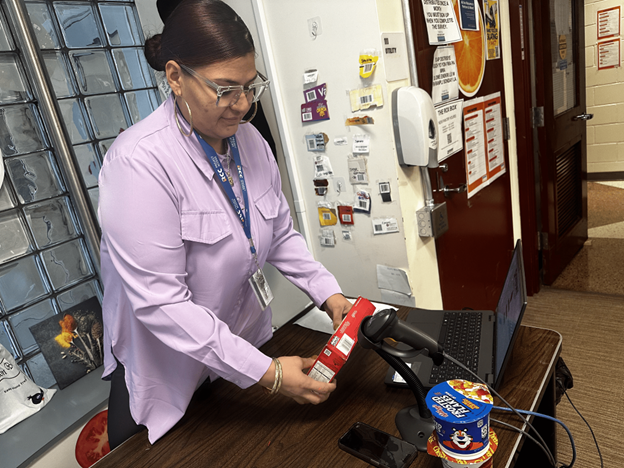

Inside the Rox Box, where students get access to free groceries and hygiene items.

Inside the Rox Box, where students get access to free groceries and hygiene items.

The surge was visible at campuses across Boston. At Bunker Hill Community College, the DISH Food Pantry—which serves more than 750 students and receives 60 percent of its food from the Greater Boston Food Bank—saw the change firsthand.

“We had a lot of folks coming to us in a more heightened state of fear and anxiety around where their next meal would come from,” said Chelsea Alexander, the DISH coordinator.

The demand extends beyond community colleges. At Northeastern University, the community fridge outside the Hillel building is restocked daily, and empties within 12 to 24 hours. “People come multiple times a day,” said Brian Fried, operations and finance director at NU Hillel.

While the recent government shutdown did cause a crisis for students like White and Rosario, the struggles were not new.White still works 60 hours weekly while pursuing her doctorate, her bills still exceeding her income. In November, she received another SNAP cancellation notice—the same bureaucratic cycle repeating itself. At Roxbury, students still face impossible choices.

“Sometimes students are literally risking going in late to class in order to make the line for the food pantry,” said Rosario.

Dining and Cooking